Wiping Out Gut Bacteria with Acute Illness Dangers: How Losing Your Microbiome Threatens Health Across the Body

Hospital treatments can disrupt friendly bacteria, while tailored care supports recovery.

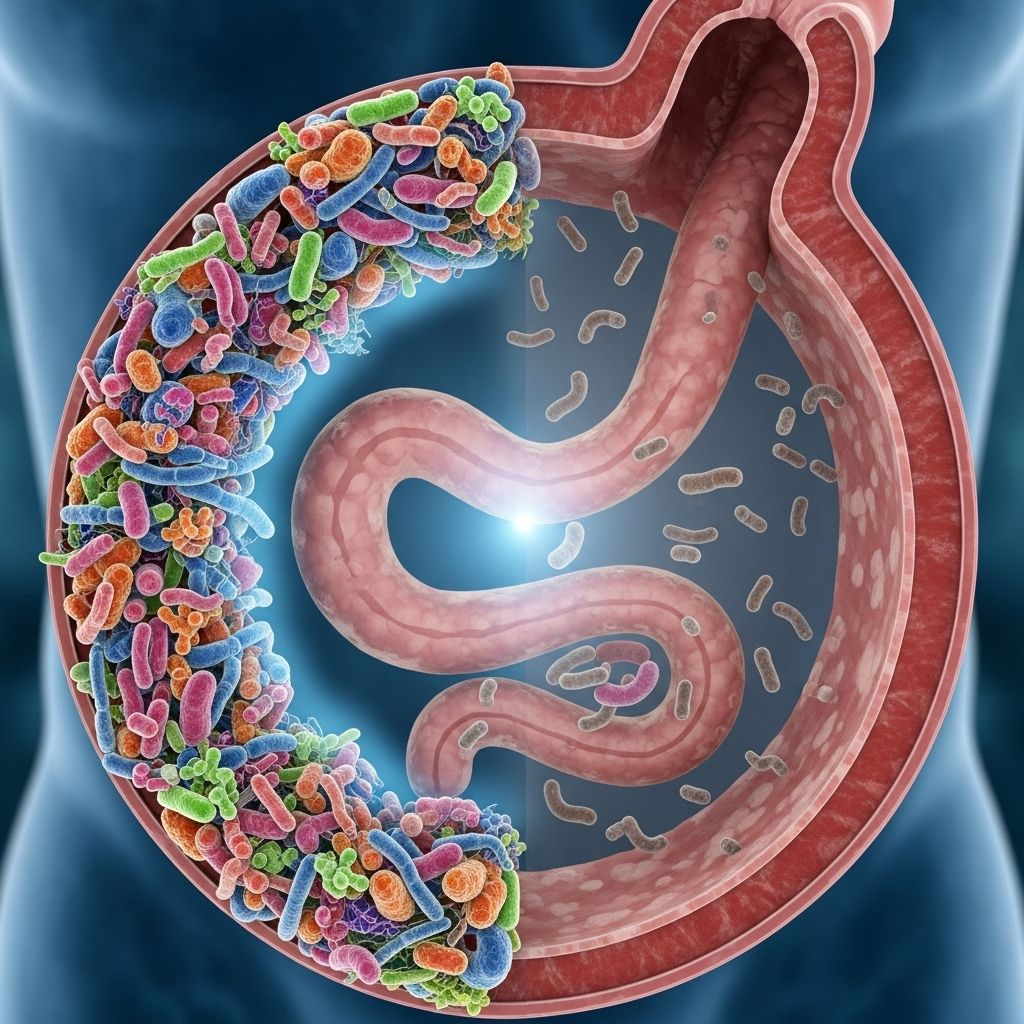

The role of gut bacteria in human health is now recognized as essential for immunity, metabolism, hormone balance, and even mental wellbeing. However, acute illness and its treatments can dramatically wipe out these helpful microbes, unleashing a cascade of dangers that extend far beyond the digestive system. This article explores the clinical and biological threats posed by gut microbiome depletion in acute and critical illness, the connections between the gut and distant organs, and what patients and clinicians can do to help protect these vital microbial allies.

Table of Contents

- Understanding Gut Bacteria: The Foundation of Health

- How Acute Illness Wipes Out the Gut Microbiome

- Gut Dysbiosis and Systemic Consequences

- Organ Systems Harmed by Wiping Out Gut Bacteria

- Dangerous Infections and the Antibiotic Paradox

- Long-Term Health Effects of Acute Microbiome Loss

- Rethinking ICU and Hospital Practices

- Protecting and Restoring the Gut Microbiome After Acute Illness

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Key Takeaways

Understanding Gut Bacteria: The Foundation of Health

The human gut teems with trillions of microorganisms. These gut bacteria—together known as the gut microbiome—form a living ecosystem that is vital for:

- Breaking down complex foods and producing vitamins (like B12 and K).

- Producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, which fuel colon cells and regulate inflammation.

- Educating and regulating the immune system.

- Protecting against invasion by pathogens (harmful bacteria and viruses).

- Interacting with the nervous system, impacting mood, cognition, and behavior.

Normally, a healthy gut microbiome is diverse, resilient, and dominated by beneficial bacterial groups, especially Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, with fewer potentially harmful bacteria (Proteobacteria).

How Acute Illness Wipes Out the Gut Microbiome

Acute illnesses—particularly those requiring hospitalization or intensive care—can devastate the gut microbiome in hours. Key causes include:

- Critical illness itself: The stress response, reduced blood flow (hypoperfusion), and inflammation trigger apoptosis (cell death) of intestinal cells and disrupt the tight barrier lining the gut, leading to leakiness and bacterial translocation.

- Starvation or fasting: Lack of normal food intake, common in ICU, depletes key nutrients for helpful bacteria.

- Antibiotic use: Broad-spectrum antibiotics, while needed for infections, indiscriminately kill both pathogenic and beneficial bacteria, often erasing more than 90% of commensal microbes within six hours of ICU admission.

- Oxidative stress and medications: Other drugs, oxygen therapy, and high stress can harm gut microbes directly.

These changes cause gut dysbiosis—a state where the balance of microbial communities is lost, leading to overgrowth of harmful bacteria and loss of protective species.

Mechanisms of Microbiome Destruction in Acute Settings

- Disruption of microbial adhesion and nutrient supply.

- Damage to mucus and physical barriers, letting pathogens invade.

- Release of inflammatory signals and immune system activation, leading to more collateral damage.

- Sometimes, the total depletion of commensal (good) bacteria niches, especially in prolonged illness.

Gut Dysbiosis and Systemic Consequences

Loss of beneficial gut bacteria is not a localized issue; it triggers sweeping effects across the body:

- Inflammation: Barrier breakdown allows microbial products (like endotoxin/LPS) to flood the bloodstream, causing systemic inflammation and immune system overdrive.

- Impaired immunity: With fewer beneficial bacteria, the immune system becomes misregulated, swinging between dangerous suppression and hyperactivity.

- Colonization by pathogens: With space and resources freed up, harmful microbes like Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, C. difficile, and Escherichia coli can dominate.

- Reduced SCFA production: Loss of butyrate-producing bacteria impairs the gut lining, increases risk for colon damage, and weakens anti-inflammatory signaling.

Organ Systems Harmed by Wiping Out Gut Bacteria

The concept of the gut as an “engine” for illness is now supported by research on various gut-organ axes:

| Axis | Mechanisms | Dangers |

|---|---|---|

| Gut-Lung Axis | Microbial metabolites influence immunity in the lungs. | Increased risk for pneumonia, influenza complications, ARDS. |

| Gut-Heart Axis | Endotoxins, inflammation drive vascular instability and damage. | Cardiovascular events, arrhythmias, heart failure, stroke. |

| Gut-Kidney Axis | Microbial toxins stress kidneys, reduce resilience. | Worse acute kidney injury, increased sepsis risk. |

| Gut-Brain Axis | Neuroactive compounds, inflammation reach brain. | Delirium, cognitive decline, mood disturbances, susceptibility to sepsis-associated encephalopathy. |

Beyond the intestines, these connections mean that gut microbiome loss in acute illness can trigger:

- Multi-organ failure

- Hospital-acquired infections (e.g., ventilator-associated pneumonia, bloodstream infections)

- Delirium and poor neurological recovery

- Persistent inflammation leading to chronic disease states

- Impaired wound healing and tissue repair

Dangerous Infections and the Antibiotic Paradox

Antibiotics are lifesaving in bacterial infection, but their widespread use in hospitalized and critically ill patients paradoxically increases the risk of major complications:

- C. difficile colitis: Most common hospital-acquired infection after antibiotics wipe out competing healthy bacteria.

- Sepsis: Gut barrier breakdown lets pathogens (e.g., E. coli, Enterococcus, Bacteroides) translocate into the bloodstream, fueling severe infections.

- Opportunistic infections: Fungal and viral invaders take over when bacterial flora are depleted.

Table: Top Pathogens Linked to Post-Illness Gut Microbiome Disruption

| Pathogen | Illness or Complication |

|---|---|

| Clostridioides difficile | Pseudomembranous colitis, severe diarrhea |

| Escherichia coli | Sepsis, abscesses, urinary tract infections |

| Enterococcus faecalis/faecium | Bacteremia, endocarditis, gut infections |

| Staphylococcus spp. | Sepsis, invasive infections |

| Fungi/Yeasts (e.g., Candida) | Systemic fungal infections |

This dangerous paradox places clinicians in a bind: treating severe infection forces them to use strategies (antibiotics, fasting) that can ultimately destroy the very microbial defenses their patients need most.

Long-Term Health Effects of Acute Microbiome Loss

Microbiome disruption during or after an acute illness can have lingering consequences even after apparent recovery:

- Persistent GI symptoms: Bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and susceptibility to chronic inflammatory diseases including IBD.

- Obesity and metabolic syndrome: Disrupted microbial composition can drive weight gain and insulin resistance.

- Mental health changes: Dysbiosis is linked to depression, cognitive deficits, and even neurodevelopmental disorders.

- Immune reprogramming: Long-term prone to allergies, autoimmunity, and reduced vaccine effectiveness.

Some studies show that, without intervention, the microbiome rarely recovers fully after severe disruption, especially in adults or elderly patients.

Rethinking ICU and Hospital Practices

Modern ICU and hospital practices are a double-edged sword: they save lives in the short term but can have unintended microbiome consequences. Critical aspects needing review include:

- Antibiotic stewardship: Limiting use to when truly necessary, choosing agents with narrower spectra, and minimizing duration can help preserve microbiota.

- Nutrition: Early enteral feeding (when feasible) supports gut barrier and microbes, while prolonged fasting worsens depletion.

- Infection control: Preventing cross-contamination and overgrowth of resistant hospital strains (e.g., VRE, MRSA).

There is growing interest in interventions such as probiotic administration, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), and even microbiome-preserving antibiotics, but these strategies require careful evaluation, especially in immune-compromised or critically ill patients.

Protecting and Restoring the Gut Microbiome After Acute Illness

As research continues to untangle the connections between the microbiome and disease, several strategies may help reduce harm:

- Prompt and judicious use of antibiotics—stop as soon as it is safe to do so.

- Opt for oral or enteral (gut) nutrition as early as possible in illness.

- Consider probiotics or synbiotics (probiotics plus fiber), especially if using broad-spectrum antibiotics or in high-risk patients—under medical supervision.

- Explore emerging therapies such as selective decontamination of the digestive tract and FMT in specific cases, balancing risks and benefits.

- After discharge, a diet rich in fiber, fermented foods, and polyphenol-rich plants may aid microbial recovery.

Individual patient risk varies; any intervention should be coordinated with medical teams experienced in intensive and post-acute care.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What causes the most gut bacteria loss during acute illness?

A: The largest drivers are broad-spectrum antibiotics, lack of normal food intake, and the stress of critical illness itself—each of which creates an inhospitable environment for healthy gut microbes, leading to their depletion within hours of hospital or ICU admission.

Q: Can the gut microbiome recover after being wiped out in the ICU?

A: Sometimes—especially in younger patients—the gut microbiome partially recovers over weeks or months. However, in adults and older patients, full recovery is rare without targeted intervention, and some negative effects may persist indefinitely.

Q: Are probiotics safe after acute illness or antibiotics?

A: For many patients, certain probiotics are safe and can help restore microbial balance. However, for immune-suppressed or seriously ill patients, risks remain, and use should be guided by a healthcare professional.

Q: What are signs of gut dysbiosis after acute illness?

A: Persistent diarrhea, bloating, abdominal pain, new or recurrent infections, reduced energy, mood changes, and even unexplained inflammation could signal ongoing dysbiosis. Medical evaluation is recommended.

Q: Can losing gut bacteria raise the risk of future chronic disease?

A: Yes, evidence suggests that prolonged dysbiosis increases the risk of metabolic disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, allergies, and neuropsychiatric conditions.

Key Takeaways

- The gut microbiome is crucial for the immune system and organ health—especially during critical illness.

- Acute illness and ICU interventions—including antibiotics—can wipe out commensal bacteria within hours, enabling pathogens and promoting dangerous systemic inflammation.

- Recovery of gut bacteria is rarely complete without targeted action, especially in adults and elderly.

- Supporting gut health with nutrition, careful antibiotic use, and—when appropriate—probiotics or fecal microbiota transplants may help reduce the dangers of wiping out gut bacteria after acute illness.

- Personalized care plans are essential for vulnerable patients leaving the ICU or hospital.

References

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11034825/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4425030/

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01065/full

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-05336-9

- https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/long-lasting-c-diff-infections-a-threat-to-the-gut-202311012987

Read full bio of medha deb