Comprehensive Guide to Post-Infectious IBS (PI-IBS): Diagnosis, Management, and Long-Term Care

Uncover hidden triggers behind persistent digestive issues and discover relief strategies.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Post-Infectious IBS (PI-IBS)

- Epidemiology and Impact

- Pathophysiology of PI-IBS

- Key Risk Factors for Developing PI-IBS

- Diagnostic Criteria and Approach

- Differential Diagnosis

- PI-IBS Management and Care Strategies

- Long-Term Care and Patient Education

- Future Directions and Research

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

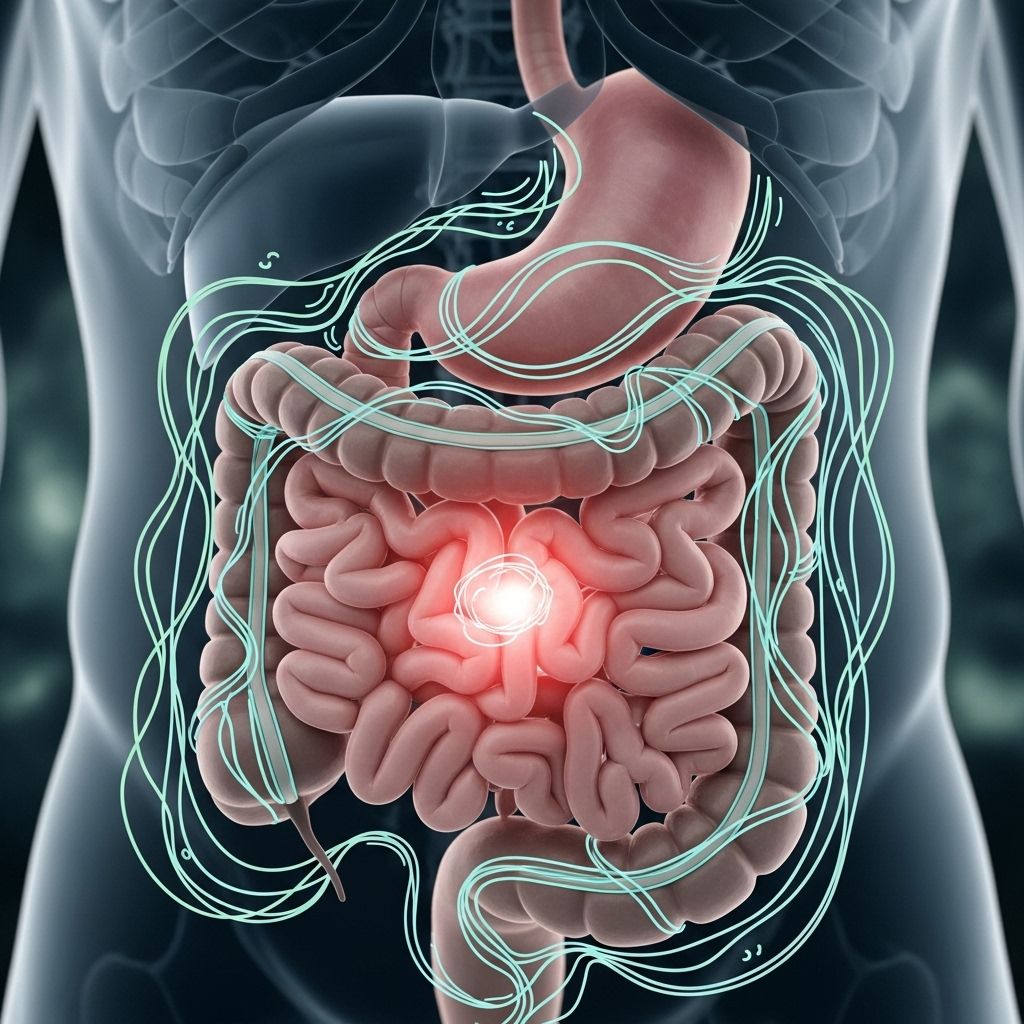

Introduction to Post-Infectious IBS (PI-IBS)

Post-Infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome (PI-IBS) is a distinct subtype of irritable bowel syndrome that emerges after an acute episode of infectious gastroenteritis. Characterized by chronic and recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, and bloating, PI-IBS lacks detectable biochemical or structural causes by conventional laboratory methods. It affects patients who previously had no IBS symptoms and is now recognized by international guidelines including the Rome IV criteria.

Epidemiology and Impact

- Incidence: PI-IBS develops in approximately 10% of individuals following bacterial, viral, or parasitic gastroenteritis.

- Burden: Up to 30% of people enduring a significant enteric infection report persistent symptoms beyond the acute phase, with a subset meeting full PI-IBS diagnostic criteria.

- Quality of Life: Chronic symptoms significantly impact daily functioning, work productivity, and mental health.

Pathophysiology of PI-IBS

PI-IBS arises due to complex interactions between the initial infection and the host response. Important mechanisms include:

- Altered intestinal sensorimotor function: Changes in nerve signaling and muscle contractions lead to pain, altered motility, and stool irregularity.

- Microbiota disturbances: Gastroenteritis disrupts normal gut flora, with incomplete recovery contributing to ongoing symptoms.

- Immune dysregulation: Persistent low-grade inflammation and immune activation following infection can affect barrier integrity and generate hypersensitivity.

- Barrier dysfunction: Increased intestinal permeability allows immune stimulants to trigger symptoms.

- Genetic factors: A genetic predisposition may modulate individual risk, though research remains ongoing.

Key Pathogens Associated with PI-IBS

- Bacterial: Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli

- Viral: Norovirus, Rotavirus

- Parasitic: Giardia lamblia

Key Risk Factors for Developing PI-IBS

Severe and protracted gastroenteritis enhances the risk of PI-IBS. Factors increasing susceptibility include:

- Female gender

- Pre-existing anxiety or depression

- Severity and duration of initial infection

- Use of antibiotics during gastroenteritis

- Genetic predisposition to inflammatory responses

Recognizing these factors during patient assessment can aid in timely diagnosis and proactive management.

Diagnostic Criteria and Approach

PI-IBS diagnosis is primarily clinical, based on symptom patterns and the history of a preceding infectious episode. The Rome IV criteria provide internationally accepted benchmarks:

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Recurrent abdominal pain | On average at least 1 day per week in the last 3 months, with onset at least 6 months before diagnosis |

| Association with defecation | Pain linked to defecation, change in frequency, or change in form of stool |

| Acute infectious episode | Symptom development immediately after resolution of gastroenteritis (documented by positive stool culture or clinical criteria: fever, vomiting, diarrhea) |

| No prior IBS | No previous diagnosis of IBS before the acute illness |

The approach includes excluding “alarm signs”—such as significant weight loss, gastrointestinal bleeding, or new-onset symptoms in older adults—using limited laboratory testing (stool tests, CBC, C-reactive protein) to rule out alternative diagnoses.

Differential Diagnosis

It is vital to distinguish PI-IBS from other conditions that may present similarly, including:

- Acute acquired hypolactasia (post-infection lactose intolerance)

- Bile acid malabsorption

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

- Lymphocytic colitis

- Persistent infection (e.g., C. difficile)

Additional diagnostic tests may be warranted if suspicion for these is high, ensuring effective treatment and avoiding mismanagement.

PI-IBS Management and Care Strategies

Currently, no specific guideline or curative treatment exists for PI-IBS; care is tailored to symptoms and subtypes (IBS-D: diarrhea predominant; IBS-C: constipation predominant; IBS-M: mixed). Key principles in management include:

Patient Education and Reassurance

- Educate patients about the link between prior gastroenteritis and current symptoms.

- Reassure patients, particularly those with viral PI-IBS, that symptoms may improve or resolve in time.

Symptom-Directed Pharmacological Therapy

- Antispasmodics (e.g., hyoscine, mebeverine) may reduce pain and cramping.

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): Effective for pain and gut hypersensitivity, with careful patient selection due to potential side effects.

- Opiates: Can slow gut transit and reduce diarrhea in IBS-D, though caution is needed for dependence and constipation risk.

- 5-HT3 antagonists: (e.g., alosetron) help with diarrhea-dominant symptoms.

- 5-HT4 agonists: (e.g., prucalopride) for constipation management.

- Cholestyramine: Useful in post-infectious bile acid malabsorption and persistent diarrhea.

Dietary and Lifestyle Interventions

- Dietary modifications: Low FODMAP diet, tailored exclusion diets based on patient tolerance.

- Gradual fiber introduction may aid some patients with constipation.

- Encourage regular physical activity and stress management techniques.

Microbiome Therapies

- Probiotics: May restore microbial balance, though evidence remains mixed for PI-IBS.

- Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT): Emerging evidence supports efficacy for select PI-IBS cases with recurrent Clostridium difficile episode; data for other infections await more study.

Algorithmic Approach to PI-IBS Management

The Rome Foundation proposes an algorithm:

- Assess symptom profile & severity

- Screen for alarm features and rule out alternative diagnoses

- Tailor therapy based on predominant symptom (pain, diarrhea, constipation)

- Monitor response and adapt as needed

Long-Term Care and Patient Education

Chronic PI-IBS necessitates ongoing support.

- Regular follow-up to monitor symptom evolution and patient coping.

- Address psychological comorbidities — anxiety, depression — via counseling or psychiatric referral if needed.

- Encourage patient involvement in their care with self-management strategies.

- Provide reassurance and discuss realistic expectations for symptom resolution.

Future Directions and Research

- Enhanced understanding of the PI-IBS pathophysiology could foster more targeted therapies.

- Genetic, environmental, and immunological research may identify high-risk individuals and preventive approaches.

- Investigation into the microbiome’s role and advanced biotherapeutics such as tailored probiotics and FMT represents a promising frontier.

- Consistent and robust clinical trials are needed to clarify the long-term efficacy of pharmacological and diet-based interventions for PI-IBS.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Can PI-IBS resolve on its own?

A: Many patients experience improvement or even resolution of symptoms over time, especially with viral-associated PI-IBS. However, a subset may have persistent symptoms and require ongoing management.

Q: How is PI-IBS different from regular IBS?

A: PI-IBS is distinguished by its onset immediately after a well-defined episode of infectious gastroenteritis, while standard IBS may develop without such a trigger and can be related to a broader set of factors.

Q: What tests confirm PI-IBS?

A: No lab test confirms PI-IBS. Diagnosis is clinical, supported by the patient’s history and the exclusion of alarm features or other diseases. Limited testing (stool culture, CBC, CRP) is used mainly to rule out other conditions.

Q: Are antibiotics or probiotics useful for treating PI-IBS?

A: Probiotics might help some patients by restoring gut microbiota, though their efficacy is not universally accepted. Antibiotics are not standard for PI-IBS unless another infection is diagnosed.

Q: Is dietary modification important for PI-IBS?

A: Yes. Dietary changes such as the low FODMAP diet and gradual fiber introduction can help mitigate symptoms, especially when customized to the person’s symptom profile.

References

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6663289/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5433563/

- https://theromefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/Rome-Foundation-Working-Team-Report-on-Post-Infection-Irritable-Bowel-Syndrome-2.pdf

- https://www.ibssmart.com/post-infectious-ibs

- https://www.gutnliver.org/journal/view.html?pn=ahead&uid=1897&vmd=Full

- https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2012/0901/p419.html

- https://webfiles.gi.org/links/PCC/ACG_Clinical_Guideline__Management_of_Irritable.11.pdf

- https://www.gastroenterologyadvisor.com/features/distinguishing-postinfectious-irritable-bowel-syndrome-from-other-ibs-subtypes/

Read full bio of medha deb