NSAIDs and Intestinal Barrier Permeability: Exploring Mechanisms, Risks, and Mitigation Strategies

Protecting the gut lining can reduce unseen digestive harm from anti-inflammatory drugs.

NSAIDs and Intestinal Barrier Permeability: The Risk

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are among the most widely used medications globally, prized for their efficacy in treating pain, inflammation, and fever. However, their benefits can come at a cost: mounting evidence shows that NSAIDs can adversely affect the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier, leading to increased intestinal permeability, gastrointestinal (GI) inflammation, and associated complications. This article offers an extensive analysis of how NSAIDs impact intestinal barrier function, the clinical ramifications and risk factors, the role of gut microbiota, and approaches to mitigate these adverse outcomes.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: NSAIDs and Intestinal Health

- The Intestinal Barrier: Structure and Function

- Mechanisms: How NSAIDs Alter Intestinal Permeability

- Clinical Consequences of Increased Permeability

- The Role of Gut Microbiota in NSAID-Induced Enteropathy

- Variability Among NSAIDs and Patient Factors

- Prevention and Mitigation Strategies

- NSAIDs Risk Comparison Table

- Frequently Asked Questions

- References

Introduction: NSAIDs and Intestinal Health

NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac, and indomethacin, exert their therapeutic effects by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, thereby reducing the synthesis of prostaglandins (PGs) responsible for pain and inflammation. While commonly known for upper GI complications—like gastric ulcers—NSAIDs also impact the small intestine, causing increased permeability, inflammation, and in some cases, more severe enteropathies. These effects can pose long-term health risks, especially for patients on chronic NSAID therapy.

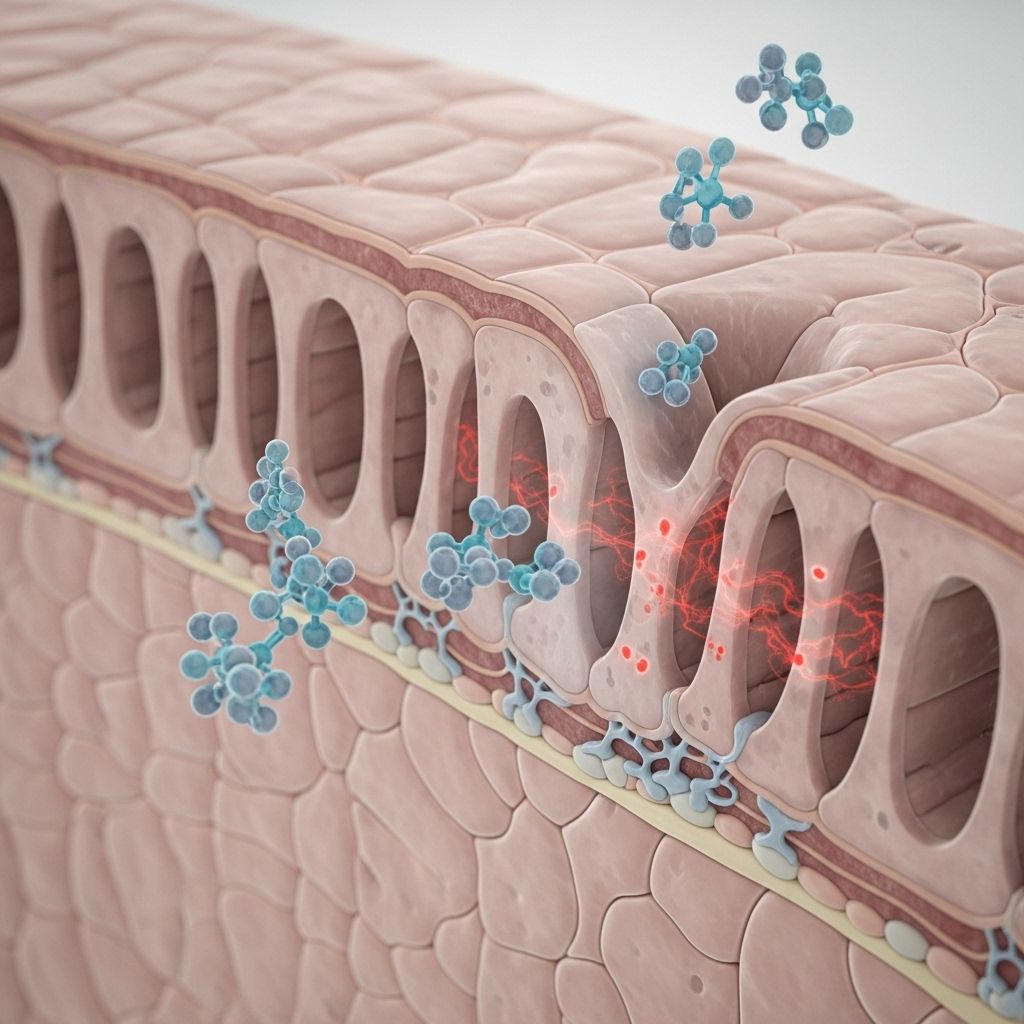

The Intestinal Barrier: Structure and Function

The intestinal barrier is a complex structure composed primarily of:

- Epithelial cells tightly connected via junctional complexes

- Mucus layer providing a physical barrier to luminal microbes and toxins

- Immune components, including intraepithelial lymphocytes and secretory IgA

This barrier regulates selective nutrient absorption while preventing luminal pathogens and toxins from entering systemic circulation. Disruption of these physical and immunologic defenses results in increased intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”), allowing unwanted antigens and bacteria to breach the mucosa and trigger inflammation.

Mechanisms: How NSAIDs Alter Intestinal Permeability

NSAIDs can compromise the intestinal barrier through several interconnected mechanisms:

- COX Inhibition and Prostaglandin Depletion

– COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes are pivotal for the production of protective PGs.

– PGs support mucosal blood flow, epithelial cell turnover, mucus secretion, and overall mucosal repair.

– NSAIDs predominantly inhibit COX-1, reducing PG synthesis and undermining mucosal integrity, especially in the small intestine, which relies on COX-1 for PG production. - Disruption of Epithelial Cell Structures

– NSAIDs interact with the phospholipid bilayer and mucus layer, causing mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum damage and oxidative stress in epithelial cells.

– This cellular damage impairs junctional complexes, increasing permeability to luminal contents. - Macroautophagy Inhibition

– NSAIDs inhibit macroautophagy (cellular recycling processes) by reducing lysosome availability in intestinal epithelial cells (IECs).

– This compromises the barrier, impairs clearance of invading microbes, and exacerbates the inflammatory response. - Facilitation of Luminal Aggressors

– Increased permeability allows bile acids, digestive enzymes, and bacteria to breach the mucosa, intensifying damage and inflammation.

NSAID-induced barrier dysfunction can become evident within 12–24 hours of drug ingestion, with inflammation detectable within 10 days and ulcer formation within two weeks .

Clinical Consequences of Increased Permeability

Alterations in intestinal permeability are not merely of biochemical concern—they have direct clinical implications, including:

- Low-Grade Intestinal Inflammation

– Chronic barrier disruption and exposure to luminal antigens can trigger ongoing mucosal inflammation. - Small Intestinal Ulcerations and Erosions

– Prolonged use may lead to mucosal breaks, erosions, and ulcers—sometimes resulting in bleeding, protein loss, or perforation. - Malabsorption Syndromes

– Induced permeability may impair absorption of crucial nutrients, potentially resulting in deficiencies and weight loss. - Enteropathy and GI Complications

– NSAID-induced enteropathy encompasses the entire spectrum from asymptomatic inflammation to overt bowel obstruction, perforation, or chronic blood loss. - No Proven Effective Prevention

– Despite various attempts with protective agents (synthetic prostaglandins, COX-2 selective inhibitors, micronutrients), no strategy has been conclusively proven to prevent NSAID enteropathy long-term .

A major study showed that up to 72% of patients on conventional NSAIDs developed small intestinal inflammation, compared to no evidence of such inflammation in those on aspirin or nabumetone .

The Role of Gut Microbiota in NSAID-Induced Enteropathy

The gut microbiota can influence both the toxicity and metabolism of NSAIDs:

- Microbial Biotransformation – Microorganisms can metabolize NSAIDs, generating compounds with altered efficacy or toxicity.

– Antibiotic suppression of gut bacteria reduces indomethacin de-glucuronidation, lowering drug re-exposure and toxicity . - Modulation of Drug Efficacy – Changes in the microbial composition can affect hepatic enzyme expression, detoxification pathways, and overall drug metabolism.

- Contribution to GI Injury – Disruption of healthy microbiota can worsen NSAID-induced permeability and increase susceptibility to inflammation and ulceration.

NSAID administration can lead to significant microbial shifts, contributing indirectly to mucosal damage and enhancing the risk of enteropathy.

Variability Among NSAIDs and Patient Factors

The risk and severity of NSAID-induced intestinal injury vary by:

- Type of NSAID

– Conventional NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac, indomethacin) are equally associated with increased permeability and inflammation.

– Exceptions: Aspirin and nabumetone appear to spare the small intestine from inflammation . - Dosage and Duration

– Both short-term and long-term use can increase permeability, sometimes within hours of ingestion . - Individual Susceptibility

– Patient factors (age, sex, dose, duration of NSAID use, underlying disease) generally do not correlate significantly with prevalence or severity of intestinal inflammation . - Co-morbid Conditions

– Conditions affecting baseline barrier integrity—such as inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, or infections—may potentiate NSAID risk.

Prevention and Mitigation Strategies

While several measures have been tested to reduce NSAID-related gut injury, none have shown definitive long-term efficacy:

- COX-2 Selective Inhibitors – Theoretically designed to spare COX-1, COX-2 inhibitors do not consistently reduce small bowel mucosal damage compared to conventional NSAIDs .

- Synthetic Prostaglandins (e.g., Misoprostol) – Supplementation with PG analogs aims to replenish protective mucosal factors, but conclusive protective effects against NSAID enteropathy have not been established .

- Micronutrients and Pre-NSAIDs – Intervention with micronutrients or agents processed prior to NSAID administration remains experimental, lacking long-term validation .

- Gut Barrier Protectants – Agents targeting the gut barrier or promoting epithelial integrity are under investigation; clinical validation is pending.

- Antibiotics or Probiotics – Modulating the gut microbiota is promising but not proven for enteropathy prevention. Probiotics may help counter inflammation or microbiota changes.

- Optimizing NSAID Use – Using the lowest effective dose, limiting therapy duration, and choosing aspirin/nabumetone when possible can reduce risk.

NSAIDs Risk Comparison Table

| NSAID | Risk of Increased Permeability | Risk of Intestinal Inflammation | Special Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ibuprofen | High | High | Rapid onset permeability change within 24h |

| Naproxen | High | High | Similar to other conventional NSAIDs |

| Diclofenac | High | High | Strong mucosal injury potential |

| Indomethacin | High | High | Significant interaction with microbiota metabolism |

| Aspirin | Low | None detected | Spares the small bowel; unique pharmacology |

| Nabumetone | Low | None detected | Spares the small bowel; safer for long-term GI health |

| COX-2 Selective (e.g., Celecoxib) | High | Comparable to conventional NSAIDs | No conclusive protective effect for the intestine |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can increased intestinal permeability from NSAIDs reverse if the drugs are stopped?

A: In many cases, permeability and low-grade inflammation improve upon discontinuation of NSAID therapy, but severe injury may require medical intervention. The timeline for recovery varies depending on the degree of mucosal damage and individual patient factors.

Q: Are there any entirely safe NSAIDs for patients at risk?

A: Aspirin and nabumetone show significantly lower risk of small intestinal inflammation than conventional NSAIDs. However, all NSAIDs have potential GI risks, and individual responses may vary.

Q: What symptoms might indicate NSAID-induced intestinal injury?

A: Symptoms may include abdominal pain, diarrhea, unexplained blood loss, anemia, malabsorption, or weight loss. However, many cases are asymptomatic until advanced injury occurs.

Q: Can probiotics prevent NSAID-induced gut injury?

A: Probiotic use is being researched for modulating gut microbiota and reducing inflammation, but robust clinical evidence for prevention of NSAID enteropathy is still lacking.

Q: Should NSAIDs be avoided in patients with inflammatory bowel disease?

A: Patients with existing barrier dysfunction, such as those with inflammatory bowel disease or celiac disease, have increased sensitivity to NSAIDs and may face greater risk. Alternative therapies should be considered when possible.

References

- Intestinal permeability and inflammation in patients on NSAIDs – PMC

- Intestinal permeability in the pathogenesis of NSAID-induced enteropathy – PubMed

- NSAID–Gut Microbiota Interactions – Frontiers

- NSAIDs disrupt intestinal homeostasis by suppressing autophagy – Nature

References

Read full bio of Sneha Tete