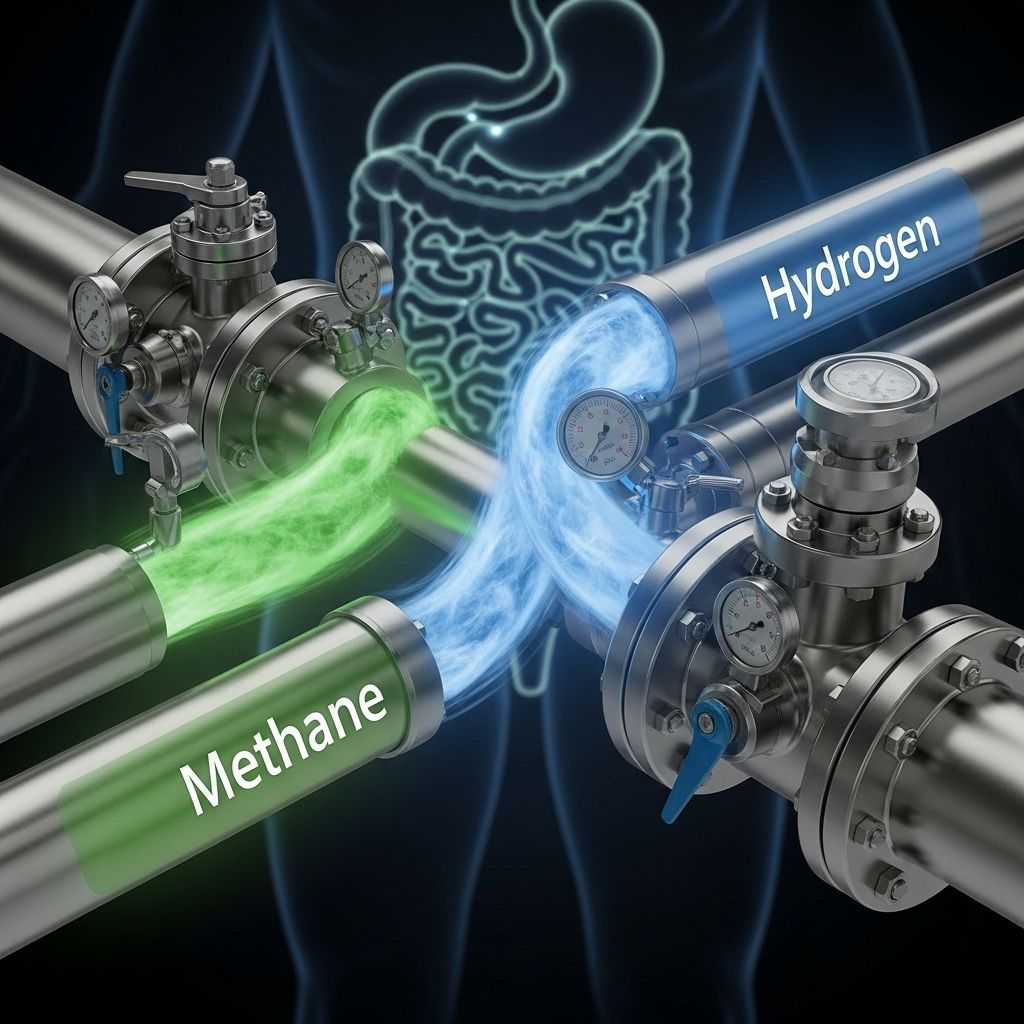

Methane vs. Hydrogen Gas in Bloating & Constipation: Understanding Gastrointestinal Gas Imbalances and Their Effects on Digestive Health

Different gut gases call for personalized testing and treatment plans.

Methane vs. Hydrogen Gas in Bloating & Constipation: Understanding Gastrointestinal Gas Imbalances

Bloating and constipation are two of the most common gastrointestinal complaints, affecting millions worldwide. Over recent decades, research has revealed that specific intestinal gases — methane and hydrogen — play significant yet distinct roles in mediating these uncomfortable symptoms. Differentiating the mechanisms and clinical implications of methane versus hydrogen is crucial for understanding digestive imbalances and optimizing therapy. This article explores the unique characteristics, physiological effects, diagnostic approaches, and optimized management strategies associated with these two key gases in the gut.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Intestinal Gases

- The Biochemistry of Methane and Hydrogen Gas

- Microbial Producers: Who Makes Methane and Hydrogen?

- Symptom Differences: Methane vs. Hydrogen

- How Gas Type Alters Gut Motility

- Diagnostic Tools: Breath Testing and Beyond

- Therapeutic Strategies

- Diet and Lifestyle Considerations

- Clinical Controversies and Additional Factors

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Introduction to Intestinal Gases

The human gut hosts a complex microbial ecosystem that ferments undigested dietary fibers, producing a range of gases as metabolic byproducts. The primary gases found in the intestine include:

- Nitrogen (N2) and Oxygen (O2): Typically inhaled with swallowed air, these are the dominant gases by volume.

- Carbon Dioxide (CO2): Produced both endogenously and via microbial fermentation.

- Hydrogen (H2): Generated from bacterial breakdown of carbohydrates.

- Methane (CH4): Formed through the consumption of hydrogen by methanogenic archaea.

While most intestinal gases are harmlessly absorbed or expelled as flatus, imbalances in hydrogen or methane production can underpin digestive disorders like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), particularly its subtypes marked by bloating and altered bowel habits.

The Biochemistry of Methane and Hydrogen Gas

Understanding the distinct biochemical origins and actions of methane and hydrogen is essential for clinicians and patients alike.

Hydrogen Gas Production

Hydrogen is produced almost exclusively by bacterial fermentation of unabsorbed carbohydrates — such as fibers, resistant starch, and some sugars — within the intestines. An overabundance of hydrogen is commonly linked to the increased presence and activity of these fermenting bacteria, which can arise in conditions such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and certain types of IBS.

Methane Gas Production

Methane is not directly produced by typical gut bacteria but by a specialized group of archaea called methanogens, the most prominent being Methanobrevibacter smithii. Methanogens utilize hydrogen as a substrate, converting it to methane through a process called methanogenesis. Thus, these two gases are inherently linked: methane production depends on available hydrogen within the gut.

Microbial Producers: Who Makes Methane and Hydrogen?

The balance of hydrogen and methane in each individual’s gut is determined by the relative abundance and activity of different microbial communities:

- Bacteria (e.g., Bacteroides, Firmicutes): Primarily ferment undigested carbohydrates to produce hydrogen gas.

- Archaea (e.g., Methanobrevibacter smithii): Consume hydrogen and produce methane.

- Other bacteria may reduce hydrogen further to produce hydrogen sulfide, another bioactive gas.

This ecological interplay means that excessive hydrogen production can “feed” methanogens, leading to increased methane levels if methanogenic archaea are present. If not, hydrogen gas may simply accumulate, with corresponding effects on gut function.

Symptom Differences: Methane vs. Hydrogen

The kind of gas predominating in an individual’s gut often predicts the type of symptoms they may experience, though there is considerable overlap:

| Gas Type | Predominant Symptoms | Typical Associated Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Methane |

| IBS with constipation (IBS-C), methane-positive SIBO/IMO |

| Hydrogen |

| IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), hydrogen-dominant SIBO |

Hydrogen SIBO usually drives faster-than-normal transit, leading to diarrhea, while methane slows gut motility and is closely tied to constipation. Importantly, symptoms are not a perfect guide; mixed cases and variations do occur.

How Gas Type Alters Gut Motility

Hydrogen Gas: The ‘Accelerator’

Hydrogen can cause intestinal distension and bloating through its sheer volume; however, it is generally considered ‘inert’ in terms of directly altering intestinal transit. Instead, excessive hydrogen production is linked primarily to explosive, loose stools typical of diarrhea-predominant IBS.

Methane Gas: The ‘Brake’

Methane exerts a much more active role. Studies in animals and humans reveal that methane gas directly slows intestinal transit by increasing gut contractility (paradoxically making contractions less effective at moving contents). This effect prolongs the time waste spends in the colon, enhancing water reabsorption and leading to harder, less frequent stools. Methane’s effect has been attributed to:

- Inhibiting gut motility via neuromuscular modulation

- Reducing post-meal serotonin levels — a key neurotransmitter that promotes bowel movement

Thus, methane’s presence is a strong marker for constipation-predominant gut disorders.

Diagnostic Tools: Breath Testing and Beyond

The assessment of gut gas production has shifted dramatically thanks to simple, non-invasive breath tests. The two most commonly used are:

- Lactulose Breath Test (LBT): Measures hydrogen and methane in exhaled breath after ingestion of lactulose, a non-absorbable sugar fermented by colonic bacteria. Elevated hydrogen suggests SIBO; elevated methane (>10 ppm) suggests methane-dominant SIBO or intestinal methanogen overgrowth (IMO).

- Glucose Breath Test: Similar approach but uses glucose as the fermentable sugar, for diagnosis of more proximal SIBO.

Additional markers or tests may be used depending on clinical context but breath testing remains the mainstay for determining the predominance of hydrogen, methane, or both.

Therapeutic Strategies

Treating bloating and constipation related to gas disturbances requires a tailored approach, depending on the underlying microbial drivers:

Treating Hydrogen-Related Symptoms

- Reducing fermentable carbohydrates (low FODMAP diet)

- Antibiotics targeted to reduce bacterial overgrowth (e.g., rifaximin)

- Probiotics to compete with gas-forming bacteria

Addressing Methane-Related Constipation

- Combination antibiotic therapy (often rifaximin + neomycin) to target both bacteria and archaea, given methanogens’ insensitivity to many common antibiotics

- Prokinetic agents to stimulate gut motility

- Addressing predisposing factors (slow transit, prior surgery, etc.)

- Long-term management to minimize risk of recurrence

Regardless of gas type, restoring a healthy gut ecosystem with an individualized diet, targeted supplements, and, where necessary, medical therapy is central to symptom control.

Diet and Lifestyle Considerations

Diet plays a major role in modulating symptoms, although responses may vary considerably. Key strategies include:

- Reducing high-FODMAP foods (especially for hydrogen symptoms)

- Considering fiber type and amount (some fibers worsen methane-related constipation by ‘feeding’ methanogens)

- Meal timing and spacing to support motility

- Stress reduction, sleep hygiene, and gentle movement (which all support gut-brain signaling and motility)

In some cases, foods that are considered ‘healthy’ — such as beans, whole grains, or fermentable vegetables — may exacerbate problems until the underlying imbalance is addressed.

Clinical Controversies and Additional Factors

- There is ongoing debate about how closely gas levels detected via breath tests correlate with symptom severity. Some studies found no association between specific hydrogen/methane levels and reported symptoms, suggesting that other factors (like visceral sensitivity and gut-brain signaling) also play a major role.

- Overlap Syndromes: Individuals may harbor both hydrogen-producing bacteria and methane-producing archaea, leading to ‘mixed’ symptoms or fluctuating bowel habits. Some may experience paradoxical diarrhea with methane dominance, particularly in complex gut disease .

- Gender and Genetic Factors: Emerging research hints at sex differences in susceptibility to SIBO/IMO, but mechanisms remain unclear .

Ultimately, while gas testing is a valuable tool, individualized assessment and a holistic treatment plan remain paramount in resolving chronic bloating and constipation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Can you have both hydrogen and methane gas problems at the same time?

A: Yes. Many cases of bloating and constipation involve both excess hydrogen and methane production, especially before methanogens consume all available hydrogen. Mixed gases can result in fluctuating diarrhea and constipation.

Q: Is methane always a bad thing for the body?

A: Not necessarily. At low levels, methane helps slow transit enough to promote nutrient absorption, but overgrowth of methanogens (e.g., Methanobrevibacter smithii) can drive severe constipation and related symptoms.

Q: Are high-fiber diets always beneficial for constipation?

A: Not always. For methane-dominant constipation, high fiber intake can worsen symptoms by fueling methanogens. Diets need to be individualized.

Q: How reliable are breath tests for diagnosing SIBO or IMO?

A: Breath tests are a widely used, non-invasive screening tool for SIBO/IMO, but results can be influenced by factors such as diet, antibiotic history, and variations in host sensitivity. Interpretation should be guided by clinical symptoms and expert consultation.

Q: Can symptoms like bloating and constipation resolve without medication?

A: In some cases, targeted dietary modifications, probiotics, and lifestyle changes can provide significant relief, but persistent cases often require combination therapy under a healthcare provider’s supervision.

References

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3678008/

- https://nutritionresolution.com/what-is-methane-sibo-the-hidden-diagnosis-behind-bloating-and-constipation/

- https://www.byronherbalist.com.au/bacterial-infection/hydrogen-vs-methane-sibo-symptoms/

- https://www.jnmjournal.org/view.html?uid=132&vmd=Full

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10132719/

- https://www.triosmartbreath.com/sibo

- https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/ibs-sibo-small-intestinal-bacterial-overgrowth-or-both-3-things-to-know

Read full bio of Sneha Tete