Mast Cells in Chronic Urticaria and Angioedema: Pathogenesis, Mechanisms, and Clinical Implications

Decoding immune signals behind persistent hives and swelling for more precise care.

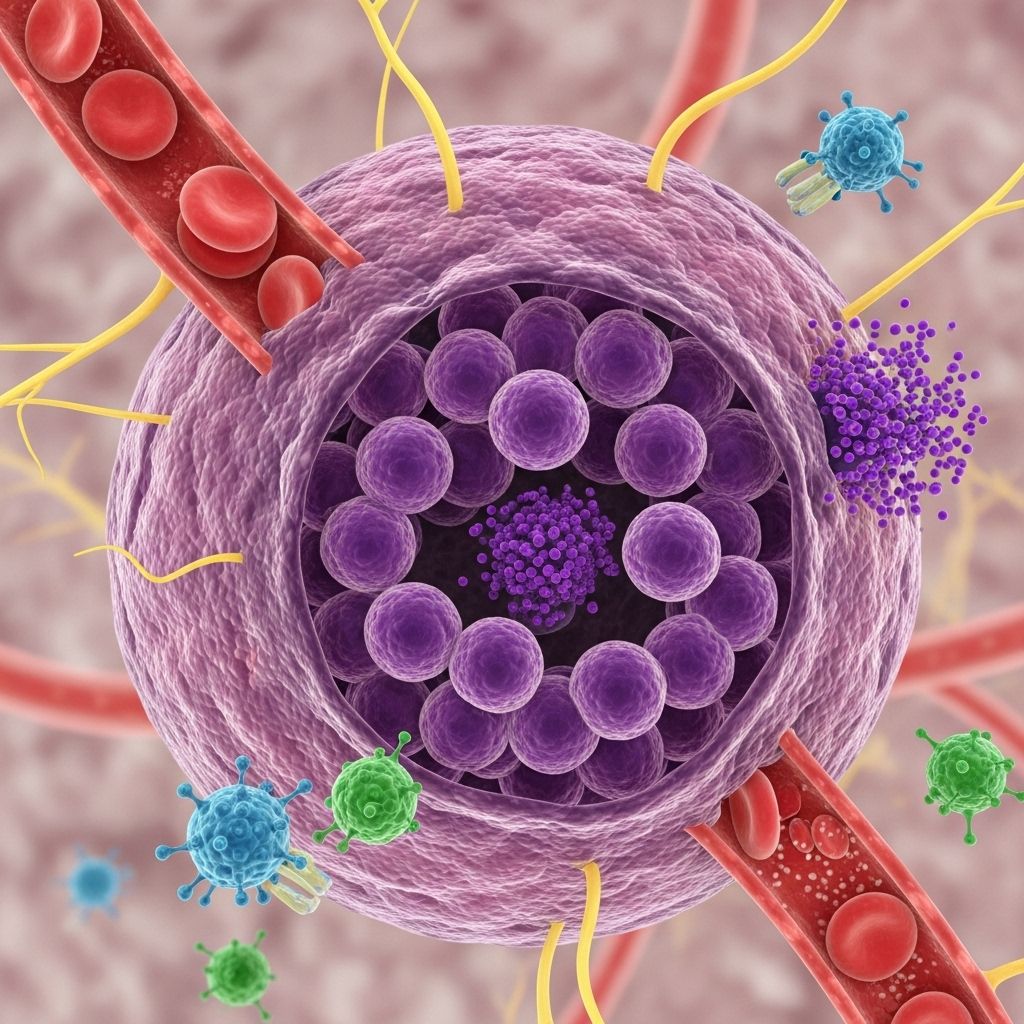

Chronic urticaria and angioedema are debilitating conditions characterized by recurrent episodes of hives and swelling. Accumulating research has established mast cells as central to their pathogenesis, acting as both the primary effectors of acute symptoms and targets of complex regulatory and autoimmune processes. This article explores the emerging science behind mast cell activation in chronic urticaria and angioedema, highlighting clinical implications for diagnosis and management.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Mast Cell Biology and Distribution

- Mechanisms of Mast Cell Activation in Chronic Urticaria

- Key Mast Cell Mediators in Urticaria and Angioedema

- Clinical Features and Forms

- Diagnostic Approaches

- Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Mast Cells

- Emerging Research and Perspectives

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Introduction

Urticaria, commonly known as hives, comprises intensely itching, erythematous wheals that may occur alone or be accompanied by angioedema—a deeper swelling typically involving mucous membranes or soft tissue. When hives or angioedema persist most days for six weeks or longer, the condition is termed chronic urticaria (CU) or chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) if no obvious external trigger is found.

Multiple lines of evidence place mast cells—immune effector cells enriched in the skin and mucosa—as core initiators of these symptoms due to their unique ability to rapidly release mediators like histamine, prostaglandins, and cytokines upon activation. The persistence, recurrence, and complexity of chronic urticaria and angioedema relate closely to dysregulation and/or inappropriate activation of these cells.

Mast Cell Biology and Distribution

Mast cells are tissue-resident, granule-containing immune cells found throughout the body but concentrated in tissues exposed to the environment (skin, airways, gastrointestinal tract). In humans, they are divided into two main subtypes:

- MCT: Contain tryptase only

- MCTC: Contain both tryptase and chymase (predominant in the skin)

Their strategic placement in the upper dermis makes them ideally situated for detecting environmental insults and triggering inflammatory responses that lead to wheal formation and sensory nerve activation in urticaria.

Key Mast Cell Characteristics

- Store pre-formed mediators (histamine, tryptase, heparin, proteases) in cytoplasmic granules

- Express high-affinity IgE receptors (FcεRI)

- Rapidly release contents (degranulation) in response to immunologic or non-immunologic stimuli

- Participate in immune defense, tissue remodeling, and neuroimmune interactions

Mechanisms of Mast Cell Activation in Chronic Urticaria

Mast cells in chronic urticaria and angioedema become inappropriately activated and undergo repeated cycles of degranulation, releasing substances responsible for the clinical manifestations. Two dominant and interlinked mechanisms drive this abnormal activation:

Autoimmune Mechanisms

Autoimmunity is considered the most evidence-supported driver of chronic spontaneous urticaria. It is estimated that up to 45% of CSU cases are autoimmune-mediated.

- Type I Autoimmunity (‘Autoallergy’): Formation of IgE antibodies targeting endogenous (‘self’) antigens leads to mast cell activation, similar to classical allergy.

- Type IIb Autoimmunity: IgG autoantibodies are produced against either the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRIα) or IgE itself on mast cells/basophils, resulting in crosslinking and activation without the need for exogenous allergen.

These autoantibodies promote chronic, low-level mast cell degranulation and persistent symptoms. Reduced function and frequency of regulatory T-cells (Treg) may also contribute to loss of self-tolerance and autoantibody production.

Supporting Evidence

- Autologous serum skin test: A subset of CU patients reacts to intra-dermal injection of their own serum, implying the presence of circulating autoimmune triggers.

- Laboratory studies: Detection of IgG anti-FcεRI or anti-IgE autoantibodies in a significant proportion of CSU cases.

- Clinical studies: Some patients with autoimmune urticaria respond to immunomodulatory therapies, further supporting the pathogenic role of humoral autoimmunity.

Intracellular Signaling and Non-Autoimmune Pathways

Not all cases are autoimmune. Other mechanisms include:

- Dysregulation of signaling pathways: Defects within mast cells or basophils may result in their inappropriate activation or trafficking, independent of external triggers.

- Non-immune triggers: Physical factors (pressure, temperature, vibration), stress, infections, and certain drugs can activate mast cells directly via non-IgE, sometimes receptor-independent mechanisms.

- Neuropeptides and cytokines: Local inflammatory mediators and nerve-derived substances (e.g., substance P, nerve growth factor) can further hyperactivate mast cells and promote Th2-skewing inflammation.

Key Mast Cell Mediators in Urticaria and Angioedema

Mast cell degranulation releases a spectrum of substances, each contributing to urticaria’s pathophysiology:

| Mediator | Effects |

|---|---|

| Histamine | Increases vascular permeability (wheal), vasodilation (flare), itching (pruritus) |

| Tryptase | Marker of mast cell activation; acts as a serine protease recruiting inflammatory cells |

| Prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) | Vasodilation, accentuation of inflammation |

| Leukotrienes (LTC4, LTD4, LTE4) | Prolonged vasodilation and edema, especially in angioedema |

| Cytokines (TNF-α, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13) | Sustain local inflammatory environment and Th2 polarization |

These mediators not only underlie typical urticarial lesions but can also stimulate nerves, perpetuate Th2 inflammation, and influence deeper tissue swelling in angioedema.

Clinical Features and Forms

Chronic urticaria is defined by daily or almost daily hives/angioedema for six weeks or more. Major clinical features include:

- Transient (<24 h), raised, and itchy wheals (usually blanchable)

- Angioedema: deeper swelling, most commonly in eyelids, lips, extremities, genitalia

- Absence of systemic anaphylaxis (typically)

- Often idiopathic, but may be associated with autoimmune markers or triggers

Subtypes of Chronic Urticaria

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria (CSU): Most common; no obvious external trigger; autoimmune and non-autoimmune mechanisms implicated

- Chronic Inducible Urticaria (CIndU): Physical or environmental triggers (cold, pressure, sun, vibration)

Angioedema

May occur alone or with hives. Symptomatically, angioedema presents as transient (<24–48 hours), asymmetric, and often painful swelling of the deeper dermis, subcutaneous, or submucosal tissues. Angioedema without urticaria is more likely to be hereditary or bradykinin-mediated (not covered here).

Diagnostic Approaches

The diagnosis of chronic urticaria and angioedema is primarily clinical, but investigations may provide insight into the underlying mast cell activity, distinguish autoimmune from non-auto immune forms, and rule out other conditions.

- Clinical history and exam: Essential for diagnosis; the morphology and evolution of lesions are characteristic.

- Autologous serum skin test (ASST): Detects circulating mast cell-activating factors; positivity may indicate an autoimmune basis.

- Basophil histamine release assay: Functional cellular test sometimes used in research to identify serum autoantibodies.

- Serum tryptase and total IgE levels: Useful in selected cases, particularly if systemic mastocytosis or autoimmune causes are considered.

- Skin biopsy: Rarely needed, but helpful if vasculitis is suspected or the diagnosis is unclear (shows mast cell infiltration and degranulation in urticaria).

Differentiating Urticaria from Other Conditions

- Urticarial vasculitis: longer-lasting lesions; may have systemic symptoms

- Hereditary or acquired angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency: non-pruritic, often familial, can be life-threatening

Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Mast Cells

Therapy for chronic urticaria and angioedema chiefly aims to suppress mast cell activation and mitigate symptoms. The following represent cornerstone and emerging approaches:

Mainstay Treatments

- Non-sedating H1-antihistamines: First-line; block the effects of histamine at the H1 receptor

- Increased dosing: Up to fourfold the standard dose may be needed in refractory cases

Second-Line and Add-On Therapies

- Omalizumab: Anti-IgE monoclonal antibody; reduces free IgE and downregulates FcεRI receptors on mast cells, often effective in antihistamine-resistant CSU (particularly autoimmune forms)

- Leukotriene receptor antagonists: May benefit a subset of patients

- Systemic corticosteroids: Short-term use only for severe flares due to long-term side effects

- Immunosuppressants (e.g., cyclosporine): Reserved for refractory, disabling cases

Experimental/Emerging Approaches

- Biologics targeting cytokines: IL-5, IL-4/IL-13 inhibitors under investigation

- Signal transduction inhibitors: Designed to block aberrant mast cell activation at the intracellular level

Emerging Research and Perspectives

Recent research has revealed:

- Greater understanding of the interplay between mast cells, T cells, and environmental triggers in perpetuating disease

- The discovery that dermal dendritic cells may prime mast cell responses via microvesicle signaling

- Identification of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1) as potential markers for disease activity

- Development of mast cell-directed therapies such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors, additional monoclonal antibodies, and gene therapy

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Are mast cells the only cells involved in chronic urticaria and angioedema?

A: Mast cells are the principal effector cells, but basophils, T lymphocytes, and dendritic cells also contribute to the inflammatory environment and can modulate mast cell activity.

Q: Is chronic urticaria always autoimmune?

A: No. While up to 45% of chronic spontaneous urticaria cases are believed to be autoimmune, other mechanisms, including non-immune triggers and intrinsic mast cell or basophil dysfunction, are also significant.

Q: Can chronic urticaria be cured?

A: Many cases enter remission spontaneously, but others can persist for years. Treatments are aimed at control, not cure, although emerging therapies offer hope for more targeted remission in severe cases.

Q: Why are antihistamines sometimes ineffective?

A: Histamine is only one of several mast cell mediators involved in urticaria and angioedema. Non-histaminergic pathways (prostaglandins, cytokines, leukotrienes) may sustain symptoms despite effective H1 blockade.

Q: What’s the role of tryptase testing?

A: Serum tryptase elevation can indicate mast cell activation and is especially useful for ruling out mast cell disorders or in evaluating severe, atypical reactions, but is not consistently elevated in all urticaria cases.

References

- (1) Frontiers in Immunology. “Autoimmune Theories of Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria.” 2019.

- (2) PubMed. “The role and relevance of mast cells in urticaria.” Immunol Rev. 2018.

- (3) PubMed Central. “Pathogenesis of Chronic Urticaria: An Overview.” 2014.

References

Read full bio of Sneha Tete