Gut Barrier Function Explained: Understanding Leaky Gut and Its Impact on Health

Stronger intestinal defenses lead to smoother digestion and improved immunity.

Gut Barrier Function Explained: Leaky Gut & Health

The gut is not only essential for digestion; it also plays a crucial defensive role, separating us from trillions of microbes, toxins, and antigens in the external environment. The functioning and integrity of the gut barrier directly influence our health, immunity, and risk of disease. This comprehensive article explores the science behind the gut barrier, the concept of ‘leaky gut,’ how barrier dysfunction may contribute to illness, and ways to support a healthy barrier.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to the Gut Barrier

- Structure of the Gut Barrier

- Core Functions of the Gut Barrier

- Leaky Gut: Definition and Mechanisms

- What Causes Leaky Gut?

- Health Impacts of Gut Barrier Dysfunction

- How Is Gut Barrier Integrity Assessed?

- Prevention and Strategies to Support Gut Barrier Health

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Conclusion

Introduction to the Gut Barrier

The gut barrier is a dynamic, multilayered defense system designed to allow the absorption of nutrients while limiting entry of toxins, antigens, and pathogens. When intact, it is a gatekeeper. When impaired, it is associated with numerous inflammatory and immune-mediated disorders, as well as metabolic diseases.

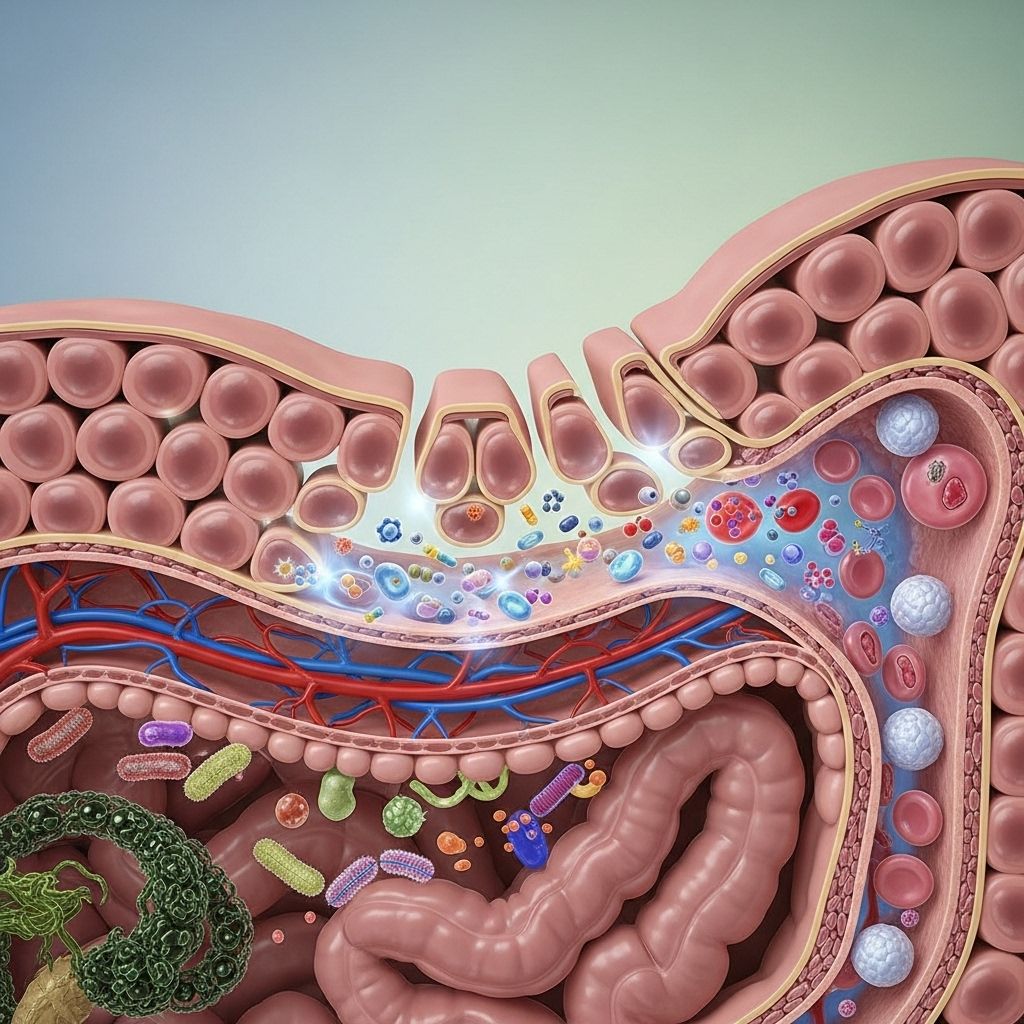

Structure of the Gut Barrier

The gut barrier is not a single wall but rather a complex, integrated structure with several interconnected layers and cell types, each with a unique function:

- Mucus Layer: A viscous, gel-like coating mainly produced by the goblet cells, rich in the mucin protein MUC2. The mucus traps microbes, preventing them from contacting the epithelium, and contains antimicrobial peptides and secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA).

- Commensal Gut Microbiota: Beneficial bacteria living in the mucosal surface help maintain barrier integrity, compete with pathogens, and modulate immune responses.

- Intestinal Epithelial Cells (IECs): A single layer of tightly connected cells (enterocytes, goblet cells, Paneth cells) that absorb nutrients and form the main cellular wall against unwanted particles. Transmembrane mucins contribute to an additional protective layer, the glycocalyx.

- Tight Junctions: Multiprotein complexes (involving claudins, occludin, and ZO proteins) seal the spaces between epithelial cells, regulating selective permeability.

- Lamina Propria: A zone just below the epithelium, filled with immune cells (T cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells) serving as a surveillance and response unit.

- Gut Vascular Barrier (GVB): The endothelial cell lining beneath the mucosa, providing a final checkpoint to microorganisms and antigens before they can enter systemic circulation.

Table 1. Layers of the Gut Barrier and Their Roles

| Layer | Main Function | Key Components |

|---|---|---|

| Mucus Layer | Physical barrier, traps pathogens, hosts microbiota | MUC2, antimicrobial proteins, sIgA |

| Microbiota | Competes with pathogens, modulates immunity | Commensal bacteria |

| Epithelial Cell Layer | Selective absorption, primary wall | Enterocytes, goblet cells, Paneth cells, mucins |

| Tight Junctions | Regulate paracellular permeability | Claudins, occludin, ZO-1, JAM2 |

| Lamina Propria | Immune surveillance and response | T/B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells |

| Gut Vascular Barrier | Prevents systemic entry of pathogens | Endothelial cells, junction complexes |

Core Functions of the Gut Barrier

- Selective Permeability: Allows absorption of water, electrolytes, nutrients, and small molecules while preventing the passage of microbes and toxins.

- Immune Defense: Maintains immune homeostasis by sampling antigens and activating appropriate immune responses when breached.

- Metabolic Regulation: Modulates the interaction between gut contents and systemic metabolism, influencing risk for obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

- Host-Microbiome Equilibrium: Provides a controlled environment for beneficial microbes, which in turn help balance gut permeability and immune responses.

Leaky Gut: Definition and Mechanisms

‘Leaky gut’ is a popular term for increased intestinal permeability—a state where the gut barrier loses its discriminatory power, permitting the passage of substances that would normally be excluded. This can allow bacterial products, undigested food components, antigens, and toxins to translocate into the bloodstream, disrupting immune and metabolic balance.

The main cellular driver of a leaky gut is disruption of tight junctions—protein structures that seal adjacent intestinal epithelial cells and regulate what can pass between them. Loss or altered regulation of tight junction proteins (e.g., claudins, occludins, ZO-1) increases paracellular permeability and is often triggered by inflammation, infections, diet, and other factors.

Mechanisms Contributing to Increased Permeability

- Degradation or altered assembly of tight junction proteins

- Epithelial cell injury or apoptosis

- Mucus layer thinning or compositional changes

- Dysbiosis: imbalance of beneficial and harmful gut bacteria

- Activation of inflammatory pathways (e.g., TNF-α, MAPK), driving disruption of cytoskeleton and junctions

- Increased production of oxidative stress or proteolytic enzymes

What Causes Leaky Gut?

Multiple internal and external factors can compromise gut barrier structure and function. These include:

- Genetics: Some people have genetic predispositions to weaker or less effective tight junctions.

- Chronic Stress: Stress hormones and inflammatory mediators can downregulate protective proteins and increase cell shedding.

- Unhealthy Diet: Diets high in fat, processed foods, alcohol, and emulsifiers have been shown to impair barrier function; while fiber, certain amino acids, zinc, vitamin D, and polyphenols help preserve it.

- Infections: Gastrointestinal pathogens (e.g., bacteria, viruses, parasites) disrupt the mucosa and tight junctions, increasing permeability.

- Drugs and Chemicals: NSAIDs, antibiotics, chemotherapy, and plasticizers like BPA are linked to barrier damage.

- Metabolic Disturbances: Obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome correlate with impaired gut barrier regulation.

- Chronic Inflammation: Immune activation in conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and celiac disease disrupts the epithelial lining.

Health Impacts of Gut Barrier Dysfunction

A compromised gut barrier allows luminal contents to enter the circulation, provoking local or systemic immune responses that have been associated with various diseases:

- Digestive diseases: Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D, others), IBD (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis), and celiac disease often exhibit increased permeability.

- Metabolic diseases: Obesity, type 2 diabetes, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease have been associated with endotoxemia (presence of gut-derived LPS in blood) and barrier dysfunction.

- Autoimmune conditions: Increased gut permeability is suggested to contribute to the development or persistence of autoimmune conditions, such as type 1 diabetes and multiple sclerosis.

- Systemic inflammation: Chronic, low-grade passage of bacterial products can sustain subclinical inflammation and alter immune balance throughout the body.

Potential Symptoms of Leaky Gut

- Digestive discomfort (bloating, cramps, irregular stools)

- Food sensitivities or allergies

- Fatigue and brain fog

- Unexplained rashes or joint pain

- Frequent infections

- This symptom cluster is not specific, making diagnosis and attribution to leaky gut controversial. More research is needed to strengthen the clinical relevance of “leaky gut syndrome” in general populations.

How Is Gut Barrier Integrity Assessed?

No single test can definitively diagnose “leaky gut.” However, researchers and clinicians use several methods to assess gut barrier structure and function:

- Lactulose-mannitol test: Oral doses of these sugars are administered, and their appearance in urine is measured to estimate permeability.

- Measurement of circulating biomarkers: Raised blood levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), zonulin, or other markers suggest increased permeability.

- Endoscopy and biopsy: Direct assessment of tissue structure and junction protein expression (e.g., claudin, occludin, ZO-1).

- Emerging molecular and imaging techniques: Used mainly in research to assess barrier integrity at high resolution.

Prevention and Strategies to Support Gut Barrier Health

Supporting the gut barrier is a multi-faceted approach, involving dietary, lifestyle, and sometimes pharmaceutical interventions:

- Dietary Fiber and Prebiotics: Promote growth of beneficial bacteria and healthy mucus production.

- Amino acids (glutamine), vitamins (D, A), zinc, and polyphenols: These nutrients reinforce barrier structure and function.

- Probiotics: Certain strains may help restore microbiota balance and attenuate inflammation.

- Minimizing processed foods and excess alcohol: Reduces exposure to barrier-damaging agents.

- Stress management: Mind-body interventions may help maintain barrier function via effects on gut-immune communication.

- Judicious use of medications: NSAIDs and antibiotics should be used with caution as they can harm the mucosa.

- Mucoprotectants and targeted therapies: Agents are under development to reinforce mucus or tight junctions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the main function of the gut barrier?

The gut barrier controls the passage of substances between the gut and bloodstream, allowing nutrients in but keeping toxins, pathogens, and harmful antigens out.

Is leaky gut recognized by mainstream medicine?

While the phenomenon of increased intestinal permeability is supported by scientific evidence, the concept of a generalized “leaky gut syndrome” as a cause for diverse symptoms is not fully accepted in mainstream clinical practice.

What diseases are linked to a leaky gut?

Digestive diseases like IBD, IBS, and celiac disease, as well as metabolic and some autoimmune conditions, show associations with impaired gut barrier function, though causality is still debated.

Can diet repair the gut barrier?

Diet can support gut barrier health—fiber, plant-based foods, certain nutrients, and microbiota-friendly ingredients have a beneficial effect, while processed foods, high fat, and excess alcohol can harm it.

How can the gut barrier be tested?

Indirectly, through tests like the lactulose-mannitol urine test or blood markers such as zonulin or LPS. Direct assessment requires tissue analysis.

Conclusion

The gut barrier is a multilayered, dynamic defense system critical for digestive, immune, and whole-body health. While the science continues to evolve, supporting barrier function through a wholesome diet, prudent medication use, and stress management appears beneficial for most people. Understanding and protecting the gut barrier may not only resolve gastrointestinal symptoms but could also shape health far beyond the digestive tract.

References

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2025.1538791/full

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6104804/

- https://www.scientificarchives.com/article/intestinal-barrier-function-a-novel-target-to-modulate-diet-induced-metabolic-diseases

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2024.1465649/full

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s12276-018-0126-x

Read full bio of Sneha Tete