Exercise and the Skin-Gut Barrier: Mechanisms, Benefits, and Clinical Insights

Nourish tissue health and microbial balance with regular, well-rounded training sessions.

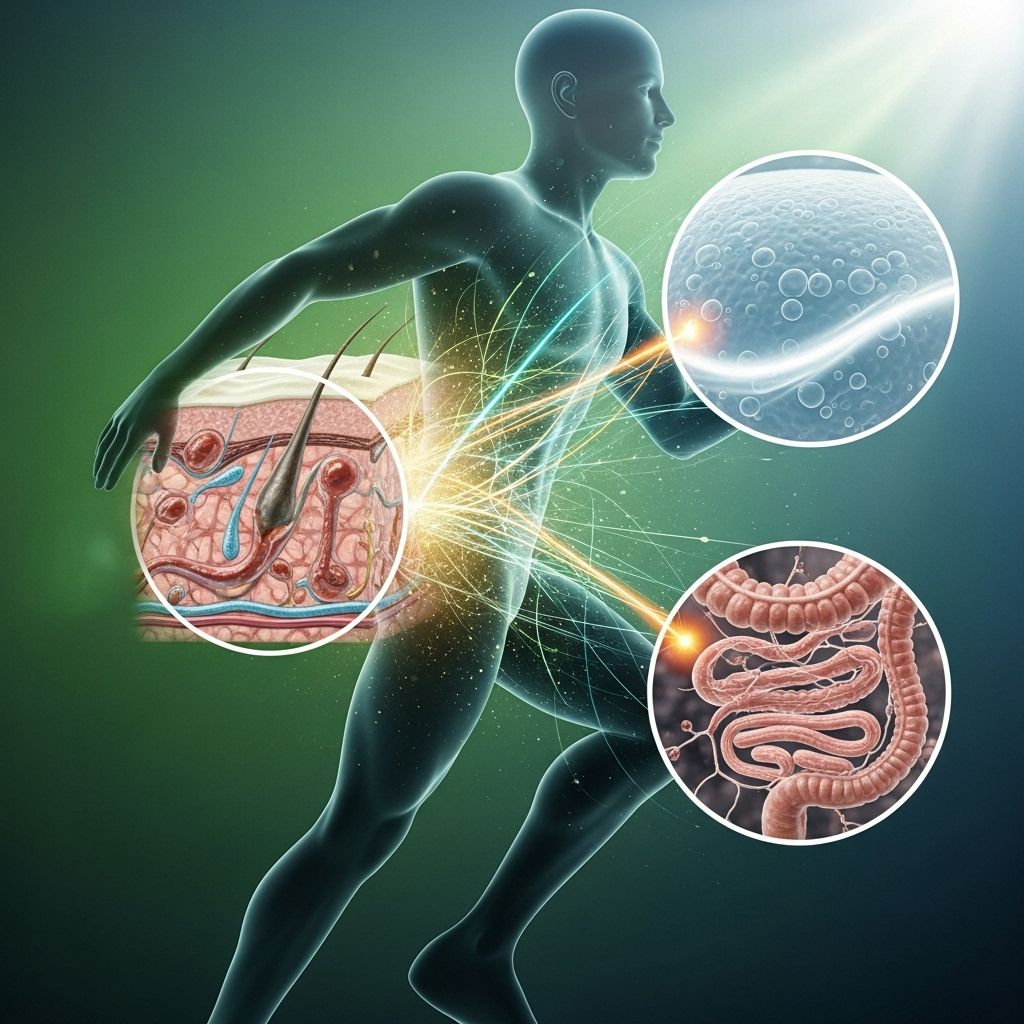

Physical activity is widely known for its profound impact on various aspects of human health, from cardiovascular strength to metabolic balance. In recent years, scientific attention has turned to the relationship between exercise and epithelial barriers—especially the skin and gut—due to their essential roles in physiology, immunity, and disease resistance. This article comprehensively explores the effects, mechanisms, and clinical implications of exercise on the integrity and function of skin and gut barriers, targeting researchers, clinicians, and health-conscious individuals alike.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Structure and Function of the Skin Barrier

- Impact of Exercise on Skin Physiology

- Molecular Mechanisms: Exercise and Skin Composition

- Exercise, Skin Moisturization, and Hydration

- Structure and Function of the Gut Barrier

- Exercise and Gut Barrier Integrity

- Molecular Mechanisms: Exercise Effects on the Gut

- Clinical and Lifestyle Implications

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Introduction

Our skin and gut are not just physical barriers—they are dynamic organs continuously interacting with the environment. The skin defends against pathogens, prevents water loss, regulates temperature, and contributes to sensory perception. The gut barrier enables nutrient absorption while blocking harmful substances. Both barriers are susceptible to environmental influences, lifestyle, and, critically, physical activity. Modern research demonstrates that regular exercise can significantly optimize their function, yielding impacts that span appearance, immunity, and overall health.

Structure and Function of the Skin Barrier

The skin barrier consists of multiple layers, the most important being the stratum corneum—the outermost layer of the epidermis. This layer comprises corneocytes (dead skin cells) embedded in a matrix of lipids, forming a “brick-and-mortar” structure essential for barrier function. The skin:

- Prevents excessive water evaporation (trans-epidermal water loss, or TEWL)

- Blocks entry of pathogens and irritants

- Maintains elasticity, resilience, and texture

- Participates in thermal regulation and immune surveillance

Barrier integrity depends on the equilibrium between cellular renewal, lipid synthesis, and tight junction proteins.

Impact of Exercise on Skin Physiology

Regular exercise exerts profound effects on skin physiology via multiple pathways:

- Enhanced Blood Flow: Physical activity significantly increases skin perfusion, supplying oxygen, nutrients, and growth factors while facilitating removal of metabolic byproducts and supporting repair processes.

(References: ) - Improved Skin Temperature Regulation: During exercise, sweat production and vasodilation regulate body heat and help maintain microenvironmental balance necessary for healthy skin.

(References: ) - Skin Moisturization: Studies show links between regular exercise and improved skin moisture retention and stratum corneum hydration, directly correlating to a healthier, more resilient barrier.

(References: )

These effects combine to keep the skin healthy, glowing, and less prone to disease.

Molecular Mechanisms: Exercise and Skin Composition

Exercise influences the molecular and cellular composition of skin in several crucial ways:

- Collagen Synthesis: Exercise stimulates the production of collagen, the principal protein providing structural integrity and elasticity to the skin. Both resistance and aerobic training upregulate the expression of key collagen genes (e.g., COL1A2, COL3A1).

(References: ) - Growth Factors & Myokines: Exercise induces release of growth factors such as TGF-β (transforming growth factor-beta) and myokines (protein messengers) like IL-15 and CXCL10 from contracting muscles. These messengers stimulate skin fibroblasts, promote angiogenesis, and enhance skin regeneration.

(References: ) - Mitochondrial Biogenesis: Aerobic training increases mitochondrial activity in skin cells (notably fibroblasts), improving tissue repair and resistance to aging.

(References: ) - Anti-inflammatory Effects: Physical activity downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as CCL28 and CXCL4) and upregulates anti-inflammatory mediators, leading to healthier dermal tissue and delayed skin aging.

(References: ) - ECM Remodeling: Exercise promotes the turnover and remodeling of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, essential for skin renewal and wound healing.

(References: )

Together, these effects increase skin elasticity, thickness, and resistance to environmental insults.

| Factor | Exercise Effect | Skin Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen (COL1A2, COL3A1) | ↑ Expression | Enhanced elasticity, thickness |

| TGF-β, FGF | ↑ Circulating levels | Promotes repair and anti-aging |

| IL-15, CXCL10 | ↓ Pro-inflammatory signaling | Improved regeneration, reduced inflammation |

| Mitochondrial content | ↑ Biogenesis | Better energy and resilience |

Exercise, Skin Moisturization, and Hydration

Skin hydration is vital for its barrier function and appearance. Research on adults who adopted moderate to vigorous exercise (at least 600 METs/week for 8 weeks) revealed:

- Increased Stratum Corneum Hydration (SC Hydration): Active participants showed a trend toward higher hydration compared to non-exercisers.

- No significant change in Transepidermal Water Loss (TEWL): Exercise did not increase water loss through the skin, suggesting improved moisture retention without compromising barrier integrity.

- Improvements tended to correlate with exercise intensity and adherence.

Thus, regular exercise may help maintain and improve the skin’s natural moisturizing function, contributing to healthier, more supple skin.

(References: )

Structure and Function of the Gut Barrier

The gut barrier is a complex, multilayered defense system lining the gastrointestinal tract. Its main features include:

- Epithelial cell layer: Tightly-joined cells prevent passage of harmful microorganisms and toxins, but allow nutrient absorption.

- Mucus layer: Protects epithelial cells from mechanical and chemical damage.

- Gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT): Immune cells monitor and respond to microbial and dietary threats.

- Microbiota: The trillions of beneficial gut microbes help modulate barrier strength, immunity, and metabolism.

A compromised gut barrier (“leaky gut”) permits entry of endotoxins and pathogens into circulation, resulting in inflammation and increased disease risk.

Exercise and Gut Barrier Integrity

Physical activity impacts the gut barrier both positively and, under certain conditions, negatively:

- Moderate Regular Exercise: Supports healthy tight junction protein expression, increases beneficial microbial diversity, and enhances mucosal immunity.

- Gut Microbiome Modulation: Athletic populations often exhibit a richer and more stable gut microbiome, which promotes barrier resilience and metabolic balance.

- Anti-inflammatory Effects: Similar to the skin, exercise reduces pro-inflammatory signals within the gut mucosa, protecting against excessive immune activation and related pathologies.

However, excessive intense exercise (especially in heat and without hydration) may temporarily increase gut permeability. This effect highlights the importance of exercise type, duration, and environmental conditions for optimal gut health.

Molecular Mechanisms: Exercise Effects on the Gut

The positive effects of exercise on the gut barrier involve diverse and interconnected molecular pathways:

- Tight Junction Protein Upregulation: Exercise enhances expression of proteins such as claudin, occludin, and zonula occludens, strengthening cell junctions.

- Short Chain Fatty Acid (SCFA) Production: Exercise-induced microbial shifts increase fermentation of dietary fiber, elevating SCFA levels (e.g., butyrate), which reinforce epithelial integrity and modulate immune responses.

- Reduction in Systemic Inflammation: Lowered circulating inflammatory cytokines benefit gut permeability and limit chronic disease risk.

- Stress Hormone Regulation: Controlled exercise reduces the impact of stress-induced hormone (e.g., cortisol) surges on gut permeability.

These mechanisms collectively create a more robust gut barrier, reducing the likelihood of “leakiness,” infection, or chronic inflammatory disease.

Clinical and Lifestyle Implications

Optimizing skin and gut barrier function through regular exercise translates to measurable health benefits:

- Enhanced Appearance: Healthier, better-hydrated, and more elastic skin.

- Disease Prevention: Lower risk of atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, acne, food allergies, metabolic syndrome, and some autoimmune disorders.

- Immune Resilience: Strengthened mucosal and cutaneous immunity, providing greater defense against pathogens.

- Systemic Benefits: Improved joint and bone density, psychological well-being, and metabolic fitness.

Recommended strategies for leveraging exercise to support barrier health include:

- Incorporating both aerobic and resistance training for comprehensive benefits.

- Avoiding excessive, high-intensity exercise without adequate hydration, especially in heat.

- Pairing exercise with nutritionally balanced diets rich in antioxidants, vitamins, protein, and fiber.

Future research will further clarify the distinct pathways by which exercise interacts with epithelial barriers, offering new therapeutic targets for clinical intervention.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1. How quickly can skin health improvements be observed after starting regular exercise?

A: Measurable improvements, such as increased hydration and enhanced skin texture, can appear within 1–2 months of regular moderate exercise, according to clinical studies.

Q2. Does the type of exercise matter for skin or gut barrier benefits?

A: Both aerobic (e.g., running, cycling) and resistance training provide benefits, but different forms may preferentially target aspects like collagen synthesis or mitochondrial health. Combining types is most effective.

(References: )

Q3. Can exercise worsen gut barrier function?

A: Excessively intense, prolonged, or unhydrated exercise (such as ultra-endurance events) can temporarily increase gut permeability. Moderate, consistent activity supports gut integrity.

Q4. Are exercise benefits on the skin limited if I have underlying skin conditions?

A: While exercise generally benefits skin health, pre-existing dermatological conditions may require tailored approaches. Consult with a dermatologist to balance exercise types and skincare routines.

Q5. How does exercise interact with diet in supporting barrier function?

A: Diet and exercise act synergistically; exercise enhances blood flow and molecular signaling, while nutrition supplies the building blocks for healthy skin and gut lining, such as amino acids, essential fatty acids, and vitamins.

Key Takeaways

- Regular, moderate exercise enhances both skin and gut barrier integrity via improved hydration, molecular signaling, and anti-inflammatory pathways.

- Benefits manifest as healthier skin, lowered disease risk, and strengthened mucosal immunity.

- Potential exists for individualized exercise regimens to optimize barrier health for various populations, including those with sensitive skin or gastrointestinal conditions.

References

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-37207-9

- https://www.pagepress.org/journals/dr/article/view/9711

- https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/wasj.2024.235

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10979338/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38483460/

- https://www.dovepress.com/the-effects-of-physical-activity-on-skin-health-a-narrative-review-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-CCID

- https://apcz.umk.pl/QS/article/view/56624

Read full bio of Sneha Tete