Endometriosis and Compromised Intestinal Barrier Function: The Microbiota Connection

A disrupted gut ecosystem drives inflammation and impacts women’s reproductive health.

Endometriosis, a chronic and frequently debilitating condition affecting at least one in ten women of reproductive age, has traditionally been viewed as a disease primarily of the reproductive system. However, recent research reveals a profound interplay between endometriosis, the gut microbiota, and the integrity of the intestinal barrier, with implications for immune function, inflammation, hormonal balance, and disease progression.

Table of Contents

- Overview of Endometriosis

- Understanding the Intestinal Barrier

- The Gut Microbiota: Structure and Functions

- The Link: Endometriosis and Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction

- Mechanisms Underlying Barrier Compromise and Disease Progression

- Clinical Implications and Comorbidities

- Diagnostics and Therapeutic Perspectives

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Conclusion and Future Directions

Overview of Endometriosis

Endometriosis is defined as the growth of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, most commonly in the pelvic cavity, ovaries, peritoneum, and, less frequently, on the intestinal serosa. This ectopic tissue responds to hormonal cycles, causing chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and often infertility. The etiology is complex and multifactorial, with prominent roles for immune dysfunction, hormonal imbalances (particularly in estrogen and progesterone signaling), inflammation, and—importantly—interactions with the gastrointestinal system.

Understanding the Intestinal Barrier

The intestinal barrier functions as a selectively permeable shield, allowing essential nutrients, electrolytes, and water to be absorbed while preventing the entry of pathogens, toxins, and antigens. Key components include:

- Epithelial cells tightly joined by proteins such as occludin, claudins, and zonula occludens (ZO proteins)

- Mucus layers secreted by goblet cells, forming a physical and immunological barrier

- Gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) providing immunological defense

- Gut microbiota, which modulate host immunity and maintain barrier homeostasis

When the barrier function is compromised—a state termed “leaky gut”—increased intestinal permeability allows microbial products such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to translocate into the circulation, provoking systemic inflammation.

The Gut Microbiota: Structure and Functions

The human gastrointestinal tract harbors trillions of microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea), collectively called the gut microbiota (GM). Its primary functions include:

- Synthesis and metabolism of vitamins, amino acids, and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)

- Regulation of local and systemic immune responses

- Modulation of endocrine signaling, particularly estrogen metabolism

- Maintenance of barrier function through modulation of tight junction proteins and anti-inflammatory effects

In healthy individuals, the GM maintains a delicate balance between beneficial and potentially harmful microbes, supporting immune tolerance and metabolic homeostasis.

The Link: Endometriosis and Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction

Emerging evidence highlights a bidirectional relationship between endometriosis and the gut environment—particularly involving the intestinal barrier and microbiota composition.

- Gut Dysbiosis: Women with endometriosis frequently exhibit gut microbiota dysbiosis, typified by an altered Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio and reduced diversity.

- Compromised Barrier: Dysbiosis leads to downregulation of key tight junction proteins (e.g., ZO-2, occludin), increasing intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”).

- Inflammation and Immune Activation: Bacterial translocation and LPS dissemination promote chronic, low-grade inflammation both in the gut and within endometriotic lesions.

This dysregulated environment potentially facilitates ectopic endometrial cell adhesion, survival, and proliferation, thus promoting the onset and progression of endometriosis.

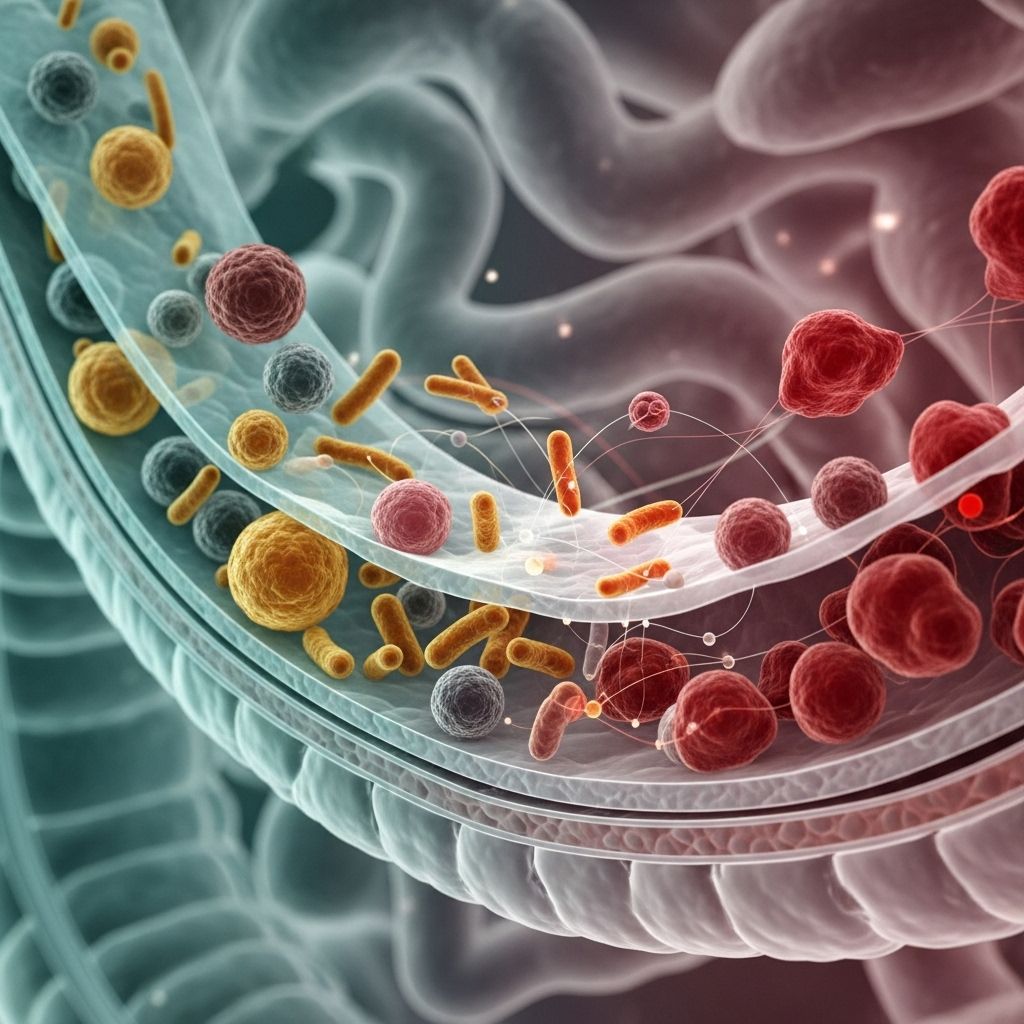

Figure: Gut Microbiota-Endometriosis Axis

Key Pathways:

- Gut microbiota imbalance → reduced tight junction protein expression → increased intestinal permeability

- LPS and microbial products cross mucosal barrier → activation of TLR4 (Toll-like receptor 4) → chronic inflammation

- Dysbiosis-related enzymes (e.g., β-glucuronidase) augment estrogen reactivation → local high estrogen environment → lesion growth

Mechanisms Underlying Barrier Compromise and Disease Progression

Gut Microbiota, Estrogen, and Immune Response

- Estrogen Metabolism: The gut microbiota, through enzymes like β-glucuronidase, reactivates conjugated estrogens excreted in bile. Elevated local estrogen levels in the pelvis encourage growth of endometriotic tissue.

- Tight Junction Disruption: Microbial dysbiosis disrupts the expression of occludin, claudins, and ZO proteins, weakening epithelial cell adhesion

- Systemic Inflammation: LPS and other microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) activate TLR4 and downstream MyD88/NF-κB pathways, inducing cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, fueling both pelvic and systemic inflammation

- Macrophage Activation: Increased permeability and endotoxin exposure activate peritoneal macrophages, which contribute to local tissue inflammation and lesion vascularization

- Angiogenesis and Lesion Implantation: Inflammatory cytokines and angiopoietins promote new blood vessel growth, supporting survival and expansion of ectopic tissue

Summary Table: Key Pathways in Endometriosis–Intestinal Barrier Crosstalk

| Pathway | Role in Endometriosis | Consequences for Intestinal Barrier |

|---|---|---|

| Gut dysbiosis | Alters estrogen metabolism, fuels inflammation | Disruption of tight junctions, increased permeability |

| LPS translocation | Activates immune cells, drives cytokine release | Mucosal injury, ongoing barrier compromise |

| Immune dysregulation | Failure to clear ectopic tissue, chronic inflammation | Impaired mucosal immunity, increased leakiness |

| β-glucuronidase activity | Increases active estrogen at lesion sites | Indirect, via hormonal and immune signaling |

| Pro-inflammatory cytokines | Supports lesion growth, pain | Barrier injury, compromised gut function |

Clinical Implications and Comorbidities

Women with endometriosis often experience gastrointestinal symptoms including abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, and features reminiscent of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or even inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Notably, population-based research reveals:

- Up to 20% of patients with endometriosis also meet diagnostic criteria for IBS

- Increased lifetime risk of IBD among women diagnosed with endometriosis

- Similarities with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in terms of mucosal inflammation, immune profile, and gut permeability

These comorbidities may be underpinned by overlapping disturbances in gut microbiota and compromised mucosal defenses.

Diagnostics and Therapeutic Perspectives

Emerging Diagnostic Biomarkers

- Microbial Metabolites: Research is evaluating SCFAs, LPS, and β-glucuronidase as diagnostic indicators and predictors of disease severity.

- Microbiota Profiling: 16S rRNA gene sequencing can identify dysbiotic signatures associated with endometriosis and gut barrier dysfunction.

Therapeutic Interventions Targeting the Gut-Barrier-Endometriosis Axis

- Probiotics and Prebiotics: Restoring a healthy microbiota may reduce inflammation, enhance barrier repair, and modulate immune responses.

- Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT): Animal studies show promising results in reducing lesion size and symptom severity, but human clinical data remain limited.

- Targeted Metabolites: Certain bacterial metabolites, notably acetate (an SCFA), mediate anti-inflammatory and barrier-protective effects and may counter lesion development.

- Anti-inflammatory Diet and Lifestyle: Diets rich in fiber, fermented foods, omega-3 fatty acids, and polyphenols support gut barrier health and may dampen endometriosis symptoms.

- Pharmacological Agents: Experimental approaches under investigation include TLR4 antagonists, β-glucuronidase inhibitors, and novel agents aimed at restoring tight junction integrity.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the connection between endometriosis and gut health?

Women with endometriosis exhibit altered gut microbiota and increased intestinal permeability, which together fuel chronic inflammation and hormonal imbalances that worsen disease severity.

How does a “leaky gut” contribute to endometriosis?

When the intestinal barrier is compromised, bacterial products like LPS translocate into the bloodstream, activating immune cells and fueling systemic and local inflammation that encourages endometrial lesion growth.

Can targeting the gut microbiota help treat endometriosis?

Therapies that restore gut microbial balance—such as probiotics, dietary modification, and potentially fecal transplant—show promise in reducing inflammation, restoring barrier integrity, and alleviating symptoms in animal models and early human studies.

Are gastrointestinal symptoms in endometriosis patients related to compromised barrier function?

Yes. Many women with endometriosis report overlapping GI symptoms similar to IBS or IBD, likely linked to increased gut permeability and mucosal inflammation from bioactive microbial products.

Is there a way to diagnose compromised intestinal barrier function in endometriosis?

Current methods are mainly research tools—such as biomarker analysis (e.g., LPS, albumin, zonulin) and gut microbiota profiling—but clinical translation is ongoing.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The intricate relationship between endometriosis, gut dysbiosis, and compromised intestinal barrier function represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of this complex disorder. Focusing on the gut barrier-microbiota-immunity nexus opens new avenues for early diagnosis, patient stratification, and innovative therapies that move beyond symptomatic management to address underlying disease mechanisms. Ongoing research will be critical to clarify causal pathways, refine diagnostic approaches, and unlock targeted, personalized interventions for women affected by endometriosis and its gastrointestinal comorbidities.

References

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2022.954684/full

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10904627/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9562115/

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1363455/full

- https://enviromicro-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1751-7915.70202

Read full bio of Sneha Tete