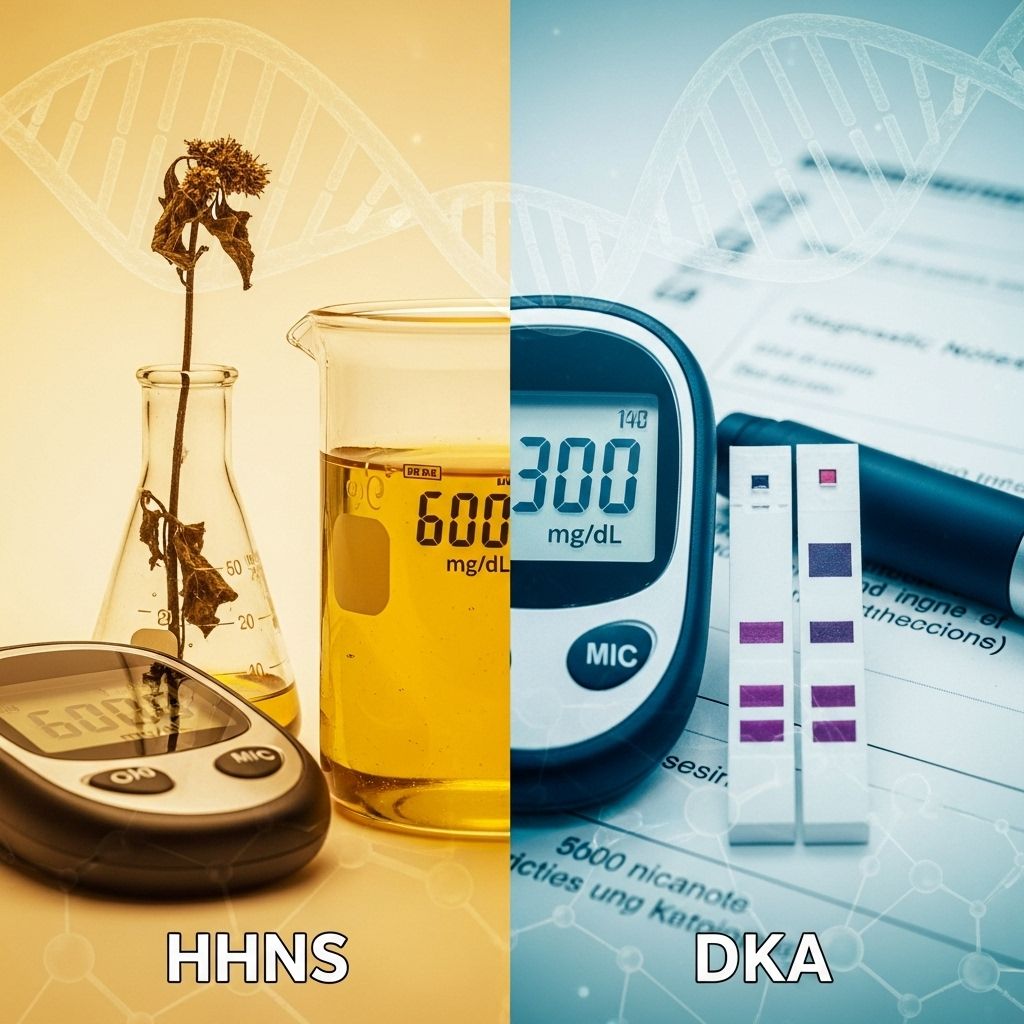

HHNS vs. DKA: Understanding Diabetes Emergency Complications

Explore the critical differences, warning signs, and treatments for two life-threatening diabetes complications: HHNS and DKA.

HHNS vs. DKA: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatments

In people living with diabetes, emergencies like Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar Nonketotic Syndrome (HHNS) and Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) can develop quickly and require immediate medical attention. While both are triggered by dangerously high blood sugar levels, their underlying causes, symptoms, and management strategies differ in important ways. Understanding the differences between them can help prevent serious complications and promote prompt, effective treatment.

What Are HHNS and DKA?

HHNS and DKA are both acute, potentially life-threatening complications of diabetes characterized by severe hyperglycemia (very high blood sugar). However, key differences distinguish one from the other—from who they typically affect to how they disrupt the body’s metabolism:

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) primarily affects people with type 1 diabetes.

- Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar Nonketotic Syndrome (HHNS, also called HHS) is more common in older adults with type 2 diabetes, but can occur in people with type 1 as well.

- DKA features ketone buildup due to fat breakdown, while HHNS rarely involves significant ketone production.

Understanding the Terminology

- DKA: A condition where lack of insulin causes blood sugar and ketone levels to rise, leading to acidosis—an acidic shift in blood pH.

- HHNS: Extreme elevations in blood sugar create hyperosmolarity, drawing water out of cells and causing severe dehydration, without significant ketone build-up.

Symptoms of HHNS vs. DKA

While there is an overlap in symptoms due to high blood sugar and dehydration, certain warning signs point more specifically toward HHNS or DKA. Being able to identify these signs can save lives by prompting faster medical intervention.

| Symptom | DKA | HHNS |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Rapid (hours) | Gradual (days to weeks) |

| Ketones | High in blood/urine | Absent or minimal |

| Blood sugar | > 250 mg/dL | > 600 mg/dL |

| Acid-base balance | Acidosis (pH < 7.3) | Normal or mild acidosis |

| Peeing/Thirst | Frequent urination, excessive thirst | Frequent urination, excessive thirst |

| Dehydration | Moderate | Severe |

| Breath odor | Fruity or acetone-like | None |

| Mental status | Confusion, drowsiness (less common) | Marked confusion, stupor, coma (more common) |

| Other signs | Nausea/vomiting, abdominal pain, rapid breathing | Seizures, visual disturbances |

Main Differences Between HHNS (HHS) and DKA

Despite some shared features, especially in the early stages, HHNS and DKA have fundamental clinical differences:

- Onset: DKA develops rapidly, often within a few hours; HHNS develops over days to weeks.

- Blood glucose: DKA usually appears with blood glucose > 250 mg/dL; HHNS typically exceeds 600 mg/dL.

- Ketones: Elevated in DKA; absent or only mildly elevated in HHNS.

- Acid-base disturbance: DKA is marked by acidosis; HHNS maintains near-normal blood pH.

- At risk populations:

- DKA: More common in younger people with type 1 diabetes

- HHNS: More often affects older adults with type 2 diabetes, but risk is present for anyone with poorly controlled diabetes

Causes and Risk Factors

Both emergencies can be triggered by situations that impair the effectiveness of insulin or greatly increase the body’s demand for insulin.

Common Triggers for Both DKA and HHNS

- Infection (most common trigger, such as pneumonia or urinary tract infection)

- Serious illness (stroke, heart attack)

- Skipping or inadequate insulin dose

- Physical or emotional stress

- Surgery or trauma

Additional Risk Factors Unique to HHNS

- Older age (especially those with type 2 diabetes)

- Dehydrating medications such as diuretics, beta-blockers, corticosteroids, or certain antipsychotics

- Undiagnosed or untreated diabetes

- Poor access to water or inability to sense thirst (due to impairment, illness, or neurological issues)

- Morbid obesity

- Family history of diabetes

Diagnosing DKA and HHNS

Prompt diagnosis is critical for both conditions. Diagnosis is based on symptoms, medical history, and laboratory results, including blood and urine tests.

Diagnostic Criteria Comparison Table

| Feature | DKA | HHNS/HHS |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Glucose | > 250 mg/dL | > 600 mg/dL |

| Serum Ketones | High | Absent or minimal |

| Arterial pH | < 7.3 (acidotic) | > 7.3 (normal–slightly low) |

| Serum Osmolality | Variable, often mildly elevated | > 320 mOsm/kg (markedly high) |

| Bicarbonate | < 18 mmol/L | > 18 mmol/L |

| Urine Ketones | Present | Absent or trace |

Potential Complications

Both DKA and HHNS can result in severe, life-threatening consequences if left untreated:

- Severe dehydration

- Electrolyte imbalances (especially potassium, which can affect heart rhythms)

- Cerebral edema (swelling of the brain)

- Shock

- Organ failure

- Coma and death

Timely treatment dramatically reduces these risks.

Treatment and Management

Immediate hospitalization is critical for both DKA and HHNS. Treatment addresses dehydration, high blood sugar, and electrolyte disturbances, while also targeting any underlying cause such as infection.

Key Elements of Treatment

- Intravenous fluids: To correct dehydration (often started immediately upon hospital arrival)

- Insulin therapy: Usually delivered intravenously to control blood sugar

- Electrolyte replacement: Especially potassium, which must be monitored and adjusted

- Treating underlying causes: Such as antibiotics for infections or management of heart attack/stroke symptoms

- Monitoring: Continuous observation of heart, kidney function, and neurological status

Differences in Treatment Approach

- DKA: Immediate insulin, aggressive hydration, and close monitoring of acidosis. Treat underlying cause as discovered.

- HHNS: Even more vigorous fluid replacement may be needed due to profound dehydration; insulin is often started after some rehydration; watch for complications from rapid shifts in fluid or electrolytes.

Who Is Most at Risk?

Understanding high-risk groups helps prevent these emergencies:

- DKA: Most common in people with type 1 diabetes, especially children, teens, and young adults. Can occur in people with type 2 diabetes, particularly during significant stress, illness, or when insulin requirements rise temporarily.

- HHNS: More typical in older adults with poorly managed or undiagnosed type 2 diabetes. Dehydration from illness or impaired thirst response increases risk markedly.

Preventing DKA and HHNS

- Monitor blood sugar levels frequently and adjust medications as needed.

- Never skip insulin or other prescribed diabetes medications.

- Increase blood glucose monitoring frequency during illness (“sick day rules”).

- Stay hydrated, especially during illness, hot weather, or if unable to eat/drink normally.

- Seek urgent medical attention for symptoms of high blood sugar, ketones in the urine, or mental status changes.

- Discuss a personalized diabetes action plan with healthcare providers, especially for managing sick days or other high-risk scenarios.

Prognosis: Recovery and Outcomes

When treated promptly, most people recover fully from DKA or HHNS. However, delays in seeking care increase the risk of lasting complications or even death. The mortality rate for DKA is under 2% with proper treatment, while HHNS has a higher risk—up to 20% or more, due largely to the older age and accompanying illnesses of those affected.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the main difference between HHNS and DKA?

DKA is marked by ketone buildup and acidosis, rapidly evolving over hours, and usually affects people with type 1 diabetes. HHNS develops over days or weeks, involves much higher blood sugar and more severe dehydration, but rarely causes ketosis, and more often affects older people with type 2 diabetes.

What are the most common triggers for HHNS and DKA?

Both can be triggered by infection, missed insulin doses, dehydration, major illness (like heart attack or stroke), or physical trauma. Certain medications and lack of access to fluids or insulin can also increase risk.

Can you have DKA and HHNS at the same time?

Yes, some patients (up to 30% in one study) may present features of both conditions. These cases require careful monitoring and tailored treatment.

How can I reduce my risk of developing DKA or HHNS?

Keep blood sugar well-controlled, check regularly (especially during illness or stress), don’t miss doses of diabetes medication, and recognize early warning signs. Seek medical help early if you notice symptoms suggestive of either emergency.

Is one condition more dangerous than the other?

HHNS generally has a higher mortality rate, partly because it often affects older people who may have additional health problems. However, DKA can also lead to life-threatening complications without prompt treatment.

When to Seek Medical Help

Anyone with diabetes experiencing symptoms like persistent vomiting, confusion, rapid breathing, severe weakness, high blood sugar unresponsive to initial treatment, or inability to keep down fluids should seek emergency medical care immediately.

- If you notice significant ketones, high blood sugar, or neurological symptoms such as confusion or drowsiness, don’t delay—immediate medical evaluation can save your life.

Summary Table: Quick Comparison of DKA vs. HHNS (HHS)

| Feature | DKA | HHNS (HHS) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical patient | Type 1 diabetes, younger people | Type 2 diabetes, older adults |

| Blood glucose | > 250 mg/dL | > 600 mg/dL |

| Serum ketones | High | Absent or mild |

| Acidosis (pH) | Yes (<7.3) | No (near normal) |

| Serum osmolality | Normal to mildly elevated | High (>320 mOsm/kg) |

| Onset | Rapid (hours) | Slow (days–weeks) |

| Key symptoms | Nausea, vomiting, fruity breath, deep rapid breathing | Severe dehydration, confusion, coma, seizures |

| Mortality rate | < 2% | 10–20% or higher |

Takeaway

Both DKA and HHNS are preventable and treatable if identified early. Monitoring diabetes closely, understanding the warning signs, and acting swiftly during illness or metabolic emergencies are crucial to saving lives. If in doubt, reach out to a healthcare provider or emergency services without delay.

References

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/diabetic-ketoacidosis-vs-hyperosmolar-hyperglycemic-state

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/hhs-diabetes-4

- https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/32/7/1335/27093/Hyperglycemic-Crises-in-Adult-Patients-With

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9669841/

- https://www.healthline.com/health/diabetes/hhns-vs-dka

- https://www.healthline.com/health/understanding-and-preventing-diabetic-coma

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9624982/

- https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000304.htm

- https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/37/11/3124/29226/Hyperosmolar-Hyperglycemic-State-A-Historic-Review

Read full bio of Sneha Tete