Understanding Eye Pressure: Normal Ranges, Causes & Risks

Learn what normal eye pressure is, why it matters, what raises or lowers it, and how eye pressure relates to diseases like glaucoma.

Eye pressure, also known as intraocular pressure (IOP), plays a crucial role in maintaining the shape, structure, and health of your eyes. Since abnormal eye pressure can put your vision at risk, understanding what is normal, what causes changes in eye pressure, and when to seek treatment are essential for lifelong eye health. This detailed guide covers everything you need to know about eye pressure, from typical ranges and risk factors to its connection with serious conditions like glaucoma.

What Is Eye Pressure (Intraocular Pressure)?

Intraocular pressure (IOP) refers to the fluid pressure inside your eye. The eye is filled with fluids that help maintain its shape and provide nutrients. One of these fluids is the aqueous humor, continuously produced by the eye and drained away to keep pressure within a healthy range. Normal IOP is crucial for clear vision and proper eye function.

Key Points About IOP:

- IOP is usually measured in millimeters of mercury (mmHg).

- Regulated by the delicate balance between fluid production and drainage within the eye.

- When drainage is blocked or fluid is overproduced, eye pressure can increase.

What Is a Normal Eye Pressure Range?

The generally accepted normal range for eye pressure is between 10 and 21 mmHg (millimeters of mercury). This range is considered appropriate for most healthy adults, though slight variations can occur from person to person.

| Eye Pressure Category | IOP Range (mmHg) | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 10–21 | Healthy pressure for most people; low risk of optic nerve damage |

| Borderline Elevated | >21 | Possible risk; warrants further evaluation and monitoring |

| Ocular Hypertension | Above 21 | Increased risk of glaucoma; may require treatment |

| Low Eye Pressure (Hypotony) | <10 | May threaten vision due to improper eye structure support |

It is important to note:

- Average IOP is about 15–16 mmHg in most people.

- Eye pressure can fluctuate throughout the day and with age.

- Some people may experience optic nerve damage at lower pressures, especially those with certain risk factors.

Why Is Eye Pressure Important?

The primary significance of IOP lies in its impact on the optic nerve. Abnormal pressures—either too high or too low—can damage the sensitive nerve fibers that relay visual information to the brain:

- High IOP (Ocular Hypertension): Increases the risk of glaucoma, a leading cause of irreversible vision loss in adults.

- Low IOP (Hypotony): Can result in structural changes and vision loss if the eye loses support from internal pressure.

In fact, untreated ocular hypertension leads to about a 9.5% risk of developing glaucoma within five years.

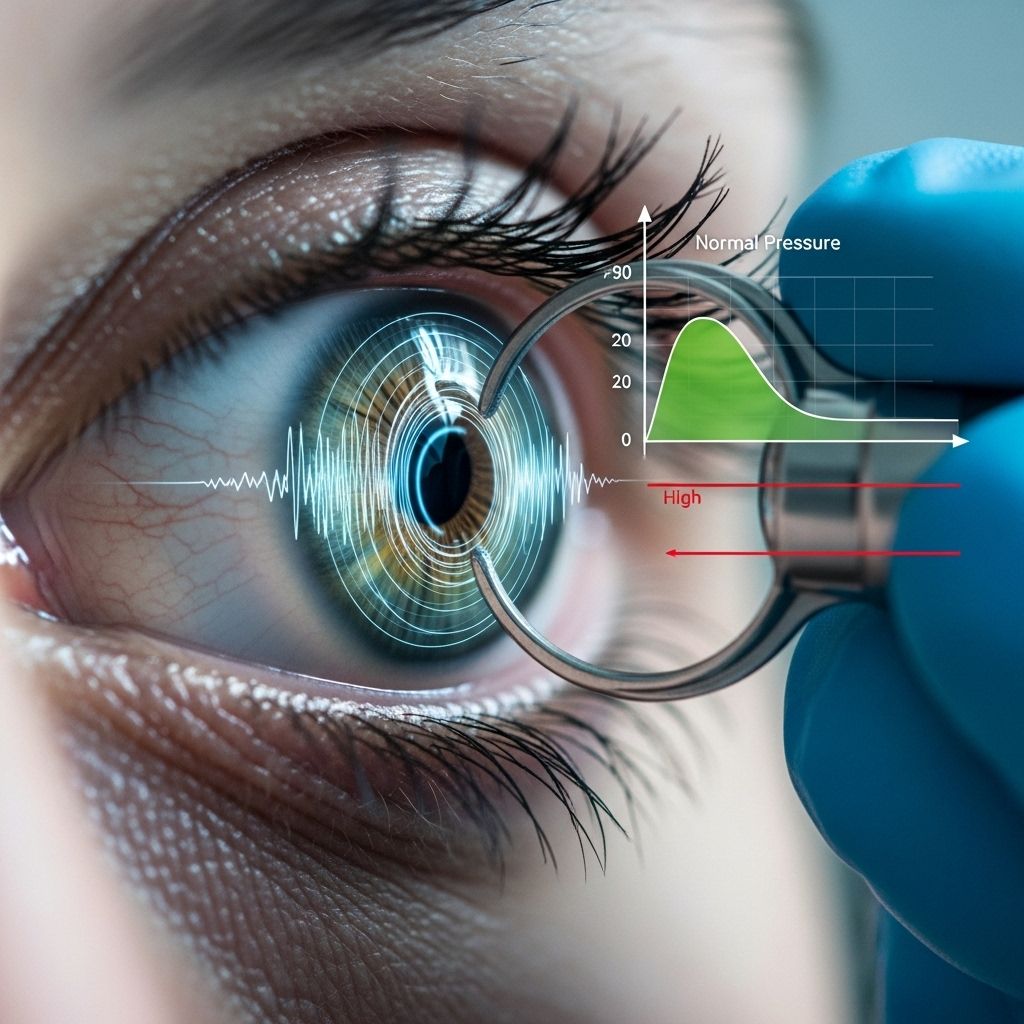

How Is Eye Pressure Measured?

Ophthalmologists use a process called tonometry to evaluate your intraocular pressure. The most common methods include:

- Applanation tonometry: Measures the force required to flatten a part of your cornea.

- Non-contact tonometry: Uses a quick puff of air to estimate pressure.

- Diaton tonometer: FDA-authorized device that measures pressure through the eyelid.

Regular eye exams are crucial as elevated IOP rarely causes noticeable symptoms until damage is advanced.

Factors Affecting Eye Pressure Levels

Multiple factors impact your eye pressure. Understanding these can help you maintain healthy vision and seek medical advice when needed:

Age

- Normal IOP tends to decrease by about 0.5 mmHg per decade of age.

- However, risk for elevated IOP and associated vision problems increases after age 40.

Genetics & Family History

- A family history of glaucoma or elevated IOP substantially increases your risk.

- IOP has a heritability estimate of around 36%.

- Having both parents with high IOP raises risk up to 76.1% for their children.

Medical Conditions

- Conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and thyroid eye disease can influence IOP, but the link is less clear than once thought.

- Systemic disease and eye trauma can also affect pressures.

Medications

- Corticosteroids (used in asthma, arthritis, and certain eye diseases) can raise your eye pressure.

- Some glaucoma medications aim to lower IOP by increasing outflow or reducing fluid production.

Lifestyle Factors

- Nutritional habits, obesity, exercise, and stress can all have minor roles in influencing IOP.

- Moderate aerobic exercise has been shown to help lower IOP in many individuals.

High Eye Pressure and Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases characterized by damage to the optic nerve, often—but not always—associated with elevated IOP.

How Does High IOP Cause Glaucoma?

- Excess pressure within the eye presses on the optic nerve, gradually damaging its fibers.

- Damage is irreversible and can lead to permanent vision loss or blindness if untreated.

- It’s possible to have normal IOP but still develop glaucoma, a condition known as “normal-tension glaucoma.”

What Causes Increased Eye Pressure?

The balance of fluid production and drainage controls IOP. High IOP is typically due to:

- Blocked or inefficient drainage system in the eye (trabecular meshwork dysfunction).

- Increased production of aqueous humor.

- Eye injuries or inflammation.

- Tumors, rare conditions, or advanced cataracts.

If fluid buildup is not addressed, pressure continues to rise, increasing glaucoma risk.

Low Eye Pressure (Ocular Hypotony)

Lower-than-normal IOP may result from trauma, surgery, or inflammatory eye disorders. Uncorrected, very low pressures can cause vision-threatening changes in the shape and function of the eye.

Symptoms of Abnormal Eye Pressure

Unusually high or low IOP often does not cause noticeable symptoms in the early stages. That’s why regular eye exams are so important for early detection and intervention.

- Persistent elevated IOP is often discovered only during routine exams.

- Acute IOP rise (as in angle-closure glaucoma) may trigger severe eye pain, headache, nausea, blurred vision, and halos around lights. Call an eye doctor immediately if these occur.

- Symptoms of low IOP (hypotony) can include distorted vision or a soft, shrunken eyeball.

Who’s at Risk for High Eye Pressure?

- People aged 40 and older

- Individuals with a family history of glaucoma or ocular hypertension

- Those of African, Hispanic, or Asian descent (increased risk for certain glaucoma subtypes)

- Long-term users of steroid medications

- People with diabetes or high blood pressure

- History of eye injury or surgery

How to Protect Your Vision

If you are in a higher risk group or have already been told you have ocular hypertension, there are steps to help protect your eyesight:

- Routine eye exams: Essential for early detection—even if you have no symptoms.

- Monitor for vision changes: Sudden changes, pain, or visual field loss need immediate medical attention.

- Lifestyle modification: Regular exercise, diabetes and blood pressure control, avoiding smoking, and healthy diet all contribute to eye health.

- Medication adherence: If prescribed glaucoma drops, use them exactly as directed.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is considered normal eye pressure?

Normal eye pressure is typically between 10 and 21 mmHg. Values over 21 mmHg are considered high and may increase your risk for glaucoma.

Is high eye pressure always indicative of glaucoma?

No. While consistently high eye pressure increases your risk, not everyone with high IOP develops glaucoma. However, monitoring is necessary to prevent potential optic nerve damage.

Can you have glaucoma with normal eye pressure?

Yes. Some individuals have “normal-tension glaucoma,” where optic nerve damage and vision loss occur despite IOP within the normal range.

Are there symptoms of high eye pressure?

Usually, elevated pressure causes no symptoms until significant damage has occurred. Acute, severe spikes in IOP, as with angle-closure glaucoma, may cause pain, headache, and vision changes and constitute a medical emergency.

What should you do if you’re at risk?

Schedule regular comprehensive eye exams, particularly if you have risk factors like age over 40, a family history of glaucoma, diabetes, or use steroid medications. Early detection can help prevent vision loss.

Summary Table: Eye Pressure at a Glance

| Condition | Description | IOP | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal IOP | Healthy pressure in most adults | 10–21 mmHg | Low |

| Ocular Hypertension | High pressure without eye damage | >21 mmHg | Moderate/High |

| Glaucoma | Optic nerve damage often linked to high IOP | Any IOP | High |

| Ocular Hypotony | Abnormally low IOP | <10 mmHg | Moderate/High |

Takeaway: Monitoring and Managing Eye Pressure

Because many changes in intraocular pressure come with no warning signs, routine eye examinations by an eye care professional are the best way to protect your vision for the long term. Individual variations mean that “normal” pressure can differ, and risk is dependent on overall eye health and other factors besides IOP alone. Stay proactive, especially if you are at higher risk, and always discuss eye pressure concerns with your healthcare provider.

References

- https://nweyeclinic.com/understanding-eye-pressure-range-and-its-importance-for-health/

- https://glaucoma.org/articles/what-is-considered-normal-eye-pressure

- http://www.webmd.com/eye-health/occular-hypertension

- https://www.cheapmedicineshop.com/blog/eyecare/eye-pressure-range/

- https://www.healthline.com/health/pressure-behind-eye

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5957383/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532237/

- https://homelessresources.networkofcare.org/Texas/HealthLibrary/Article?docType=na&articleId=hw153259

Read full bio of medha deb