Evaluation of a First-Time Seizure: Clinical Approach and Key Considerations

Comprehensive guidance on diagnosing, assessing, and managing a first-time seizure, covering causes, tests, risks, and prognosis.

Evaluation of a First-Time Seizure

A seizure can be a frightening and life-altering event for patients. The clinical evaluation of a first-time seizure is central to medical diagnosis, future risk assessment, and effective treatment planning. This article discusses the process of evaluating a first seizure, including causes, clinical features, diagnostic steps, prognosis, risk of recurrence, special considerations, and important FAQs.

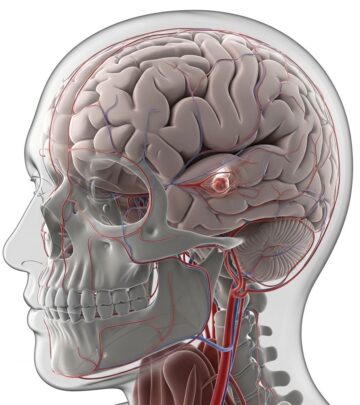

What Is a Seizure?

A seizure is a transient event caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Symptoms may range from involuntary movements and unconsciousness, to subtle changes in awareness, sensation, or emotion. Seizures are classified by their appearance (semiology), duration, and underlying causes. Not all seizures indicate epilepsy, a chronic tendency for recurrent unprovoked seizures.

Initial Considerations: Urgency and Immediate Actions

- If a person presents with a first-time seizure, ensure they are safe and evaluate for immediate medical emergencies.

- Emergency action is warranted if the seizure lasts longer than five minutes, repeats without recovery, or if the person shows signs of injury, infection, or other serious illness.

- Stabilize airways, breathing, circulation, and vital signs.

Distinguishing Seizure Types and Causes

Determining the type of seizure and whether it is provoked or unprovoked is crucial:

- Provoked (Acute Symptomatic) Seizures: Caused by a reversible medical condition (e.g., metabolic disturbance, high fever, medication/toxin effects, trauma, or stroke).

- Unprovoked Seizures: Occur without an identifiable acute cause and may signal a predisposition to epilepsy or a chronic brain abnormality.

A thorough medical history can aid in differentiation:

- Recent illnesses, drug use, or injuries.

- Family history of seizures or epilepsy.

- Descriptions by witnesses (duration, movements, confusion, recovery).

Common Non-Epileptic Seizure Mimics

- Syncope (fainting)

- Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (stress-related)

- Transient ischemic attacks (mini-stroke)

- Sleep disorders

Clinical History and Description of Events

A detailed clinical history is the foundation for diagnosis. Information to gather includes:

- Timing and context of the event (during sleep, after illness, during exercise, etc.).

- Onset (sudden or gradual), duration, and progression of symptoms.

- Prodrome or aura (warning symptoms like strange smells, feelings, or visual phenomena).

- Movements during the event (convulsions, stiffness, automatisms).

- Post-event recovery (confusion, tiredness, rapid return to baseline).

- Witness account if available, as patients may have amnesia for the event.

Physical Examination

The physical exam helps identify neurological deficits, injuries, or clues to underlying causes:

- General assessment of conscious state and orientation

- Neurological examination (cranial nerves, reflexes, muscle strength, coordination)

- Signs of trauma or infection

- Cardiovascular and systemic review

Diagnostic Tests and Laboratory Studies

Initial laboratory workup may include:

| Test | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Complete blood count, glucose, electrolytes | Detect metabolic, infectious, or electrolyte abnormalities |

| Liver and kidney function tests | Exclude organ dysfunction or toxin influences |

| Toxicology screening | Rule out drug or alcohol-induced seizures |

| Pregnancy test (if applicable) | Identify pregnancy-related causes |

| Infectious workup | If fever or immunosuppression present |

Neuroimaging

- CT scan: Often performed urgently to detect acute bleeding, stroke, or mass.

- MRI: Provides higher sensitivity for structural brain lesions, tumors, old strokes, and subtle abnormalities.

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

- EEG records the brain’s electrical activity and can reveal epileptiform abnormalities, guiding diagnosis and risk assessment.

- A normal EEG does not rule out epilepsy, but epileptiform findings (spikes, sharp waves) increase risk of recurrence.

- New tools such as network analysis of EEG signals may help detect epilepsy even when classic abnormalities are absent.

Assessing Risk of Recurrence

Key risk factors for future seizures after a first unprovoked seizure include:

- Prior brain injury, insult, or lesion (stroke, trauma, tumor)

- Abnormal EEG showing epileptiform discharges

- Significant abnormal findings on brain imaging

- Nocturnal (sleep-related) seizures

Less than half the people who experience a first unprovoked seizure will have a second seizure; however, the presence of these risk factors increases the likelihood and may alter treatment decisions.

Epilepsy Diagnosis: Definitions and Thresholds

- Historically, epilepsy was diagnosed only after two unprovoked seizures.

- The 2014 International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) definition now includes individuals with one unprovoked seizure if their future risk is at least 60% over the next 10 years.

- This risk threshold is based on specific features identified in population studies.

Treatment Considerations After a First Seizure

Immediate Treatment vs. Waiting

- Immediate use of anti-seizure drugs (AEDs) is debated after a first unprovoked seizure.

- AED therapy can reduce short-term risk of recurrence but does not improve long-term prognosis or increase chances of permanent remission.

- Risks and benefits of medications must be weighed, as AEDs have potential side effects and may impact quality of life.

- If the patient has more than one seizure, AED initiation is generally accepted due to much higher recurrence risk (over 50% in the first year, up to 75% within four years).

Adverse Effects of Anti-Seizure Medications

- AEDs may cause fatigue, dizziness, cognitive changes, mood disturbances, and rare but serious reactions such as rashes or organ toxicity.

- Side effect profiles and pharmacodynamics are particularly important in special populations (children, pregnant patients, elderly, those with comorbidities).

Social and Psychological Impacts

- Even a single seizure can cause anxiety about recurrence, driving, and employment.

- Legal limitations may apply to driving and certain job duties until further evaluation.

- Education and support resources can improve coping and adherence to follow-up care.

Special Circumstances and Considerations

- Children: Guidelines for pediatric patients differ and require risk stratification based on age, developmental status, and seizure phenotype.

- Women of Childbearing Age: Considerations around teratogenic potential of AEDs and the need for effective contraception or folate supplementation.

- Comorbidities: Medication selection and diagnostic priorities may be affected by underlying conditions such as cardiovascular disease or psychiatric illness.

Follow-Up and Patient Counseling

- Close follow-up is required to monitor for recurrence, side effects, and adjustment in therapy.

- Patients should be aware of reported risk factors and their implications for lifestyle (e.g., driving restrictions until cleared).

- Primary care physicians and neurologists collaborate on ongoing care and decision-making.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What should I do if I witness a seizure?

Stay calm, ensure the person is safe, turn them onto their side if possible, and do not restrain movements. Call emergency services if the seizure lasts more than five minutes or if injury occurs.

Q: Does having one seizure mean I have epilepsy?

No. Epilepsy is diagnosed after two or more unprovoked seizures, or after a single seizure if risk factors predict a high likelihood of recurrence.

Q: Will I need lifelong medication after my first seizure?

Not necessarily. Many patients will not have a recurrence or may not require long-term therapy. Medication decisions depend on risk assessment and discussion with your doctor.

Q: Can a normal EEG rule out epilepsy?

No. A normal EEG does not exclude epilepsy, though an abnormal EEG may increase the likelihood of future seizures. Advanced tools may improve diagnostic sensitivity.

Q: What actions should I avoid after a first seizure?

Do not drive, swim alone, or operate heavy machinery until cleared by a physician. Discuss legal requirements with your doctor based on local regulations.

Summary Table: Key Aspects in Evaluating a First-Time Seizure

| Evaluation Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| History & Witness Account | Detailed description, context, and prodromal symptoms |

| Physical & Neurological Exam | Screening for neurological deficits or injuries |

| Laboratory Tests | Rule out metabolic or infectious causes |

| Neuroimaging | Detection of structural brain abnormalities |

| EEG | Assessment for epileptiform activity |

| Risk Stratification | Identification of factors for recurrence |

| Treatment Planning | Decision on immediate versus delayed AED therapy |

References and Resources

- American Academy of Neurology: Clinical guidelines for seizure management

- International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE): Updated definitions and risk assessment protocols

- Johns Hopkins Epilepsy Center: Research on advanced diagnostic tools for epilepsy

Conclusion

Evaluating the first seizure is a multidisciplinary process, grounded in careful clinical history, diagnostic testing, and risk assessment. Accurate distinction between provoked and unprovoked seizures, use of EEG and neuroimaging, and tailored treatment planning are essential for patient safety and long-term neurological health. Close follow-up and patient education can mitigate risks and improve quality of life after a first seizure.

References

Read full bio of medha deb