CMML vs. CML: Understanding the Key Differences in Chronic Leukemias

Learn how chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) differ, from diagnosis and symptoms to prognosis and treatment approaches.

Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) are two distinct types of blood cancers that often share some overlapping symptoms and arise from similar types of cells. However, these conditions differ greatly in their underlying causes, how they affect the body, approaches to treatment, and their long-term outcomes. This article provides an in-depth look at both CMML and CML, helping patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals understand their unique characteristics.

Overview: What Are CMML and CML?

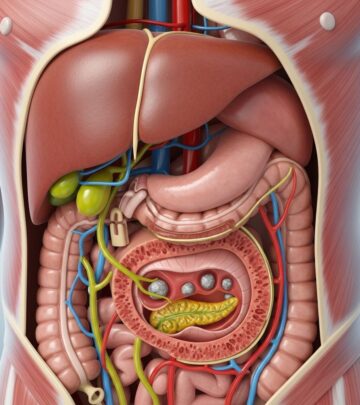

Both CMML and CML are classified as myeloid leukemias — cancers arising from myeloid stem cells found in bone marrow. These stem cells typically form three types of blood cells:

- Red blood cells (RBCs): Carry oxygen throughout the body.

- White blood cells (WBCs): Help fight infection.

- Platelets: Aid in controlling bleeding and clotting.

Despite their similar origins, CMML and CML impact distinct cell types and exhibit important differences in their genetic markers, classification, symptoms, and management.

Key Differences Between CMML and CML

| Feature | CMML | CML |

|---|---|---|

| Main WBC type affected | Monocytes | Granulocytes |

| Typical genetic cause | Multiple acquired genetic/chromosomal changes (specific cause often unknown) | Philadelphia chromosome (BCR-ABL1 fusion gene) |

| Classification | CMML-0, CMML-1, CMML-2 (based on percentage of blast cells) | Chronic, Accelerated, Blastic phases (based on blast count) |

| Estimated new U.S. diagnoses (2021) | 1,100 | 9,110 |

| Common treatments | Watchful waiting, stem cell transplant, chemotherapy, supportive care | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, stem cell transplant, chemotherapy, supportive care |

CMML: Understanding Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia

CMML is a rare type of leukemia characterized primarily by a persistent elevation of monocytes, a type of white blood cell, in the blood and bone marrow. Monocytes are normally involved in fighting infections, but in CMML, many are poorly developed and function abnormally. Additionally, immature blast cells may also rise in number.

Classification of CMML

CMML is further categorized by blast cell counts (immature cells) in the blood and bone marrow:

- CMML-0: <2% blasts in blood, <5% in bone marrow

- CMML-1: 2–4% blasts in blood, 5–9% in bone marrow

- CMML-2: 5–19% blasts in blood, 10–19% in bone marrow

CMML possesses unique features of both myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS, characterized by abnormal cell development) and myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN, involving excess production of cells), making diagnosis and management complex.

CMML: Common Symptoms

Symptoms of CMML may be subtle at first but can become more pronounced as the disease progresses. Common symptoms include:

- Persistent fatigue or weakness

- Fever and frequent infections

- Unexplained weight loss

- Anemia (paleness, shortness of breath)

- Bleeding or bruising more easily

- Night sweats

- Enlarged spleen or liver (causing discomfort in upper left abdomen)

CMML: Underlying Causes

The precise cause of CMML remains unknown. However, it is believed to result from acquired genetic or chromosomal abnormalities within bone marrow stem cells. Unlike CML, CMML does not feature the Philadelphia chromosome. Environmental exposures and increasing age may raise the risk, but most cases occur without any known risk factor.

CMML: Diagnosis

Diagnosing CMML involves a combination of:

- Blood tests (checking elevated monocyte counts and overall cell numbers)

- Bone marrow biopsy (assessing for abnormal cell maturation and blast counts)

- Genetic and chromosomal analyses

- Imaging (to assess spleen or liver enlargement)

CMML: Treatment Options

- Watchful waiting may be appropriate in early, mild cases, especially for older adults or those with few symptoms.

- Supportive care to manage symptoms, such as blood transfusions, antibiotics, or medications to increase blood cell counts.

- Chemotherapy, including hypomethylating agents, may help slow disease progression or prepare for transplant.

- Stem cell (bone marrow) transplant is the only potentially curative option but is typically reserved for younger or fit patients due to the risks involved.

CML: Understanding Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

CML is a type of leukemia where myeloid stem cells divide uncontrollably, leading to an oversupply of abnormal granulocytes (a subtype of white blood cells). A hallmark of CML is the presence of the Philadelphia chromosome, which results from a translocation that creates the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene. This gene produces an abnormal tyrosine kinase protein driving cancer growth.

CML Progression Phases

- Chronic phase: <10% blasts; usually few or no symptoms. Most patients are diagnosed at this stage.

- Accelerated phase: 10–19% blasts; symptoms become more noticeable, disease may resist some treatments.

- Blastic phase: ≥20% blasts; symptoms rapidly worsen, and the disease behaves like acute leukemia, becoming life-threatening.

Note: Some newer guidelines now combine only chronic and blast phases, omitting ‘accelerated,’ due to modern therapies’ impact.

CML: Common Symptoms

- Fatigue or weakness

- Fever and night sweats

- Pain or discomfort in or around bones

- Unexpected weight loss

- Unexplained bleeding or bruising

- Enlarged spleen (causing upper left abdominal swelling or discomfort)

CML: Underlying Causes

Over 90% of people with CML possess the Philadelphia chromosome. This genetic change causes the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene, prompting excessive cell growth and reduced normal cell maturation. The triggers for this chromosomal switch are usually sporadic and not inherited or related to specific environmental exposures.

CML: Diagnosis

A diagnosis of CML involves several steps:

- Blood count tests (showing high granulocyte counts and immature blast cells)

- Bone marrow biopsy (identifying abnormal cell growth, blast percentage)

- Genetic testing for the Philadelphia chromosome (BCR-ABL1 fusion gene)

- Cytogenetic studies and molecular analyses

CML: Treatment Options

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs): The mainstay of treatment; these medications (e.g., imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib) block the cancer-driving BCR-ABL1 enzyme and can keep CML in remission for many years.

- Chemotherapy: Used less frequently, often in advanced or resistant cases.

- Stem cell transplantation: Recommended in select cases, particularly those who are young or whose cancer does not respond to TKIs.

- Supportive care: Addressing anemia, bleeding, infections, or other side effects throughout the disease course.

CMML vs. CML: Similarities and Shared Aspects

- Both are chronic leukemias that develop from myeloid stem cells.

- Both can cause fatigue, anemia, increased risk of infection, bleeding, night sweats, and unexplained weight loss.

- Diagnosis in both relies on blood tests, bone marrow examination, and genetic analysis.

- Supportive care (like transfusions and antibiotics) is important for symptom management in both diseases.

- Stem cell transplantation can be potentially curative in select patients for either condition.

Comparing Prognosis: What to Expect Long Term

Prognosis for each condition depends on several factors, including age at diagnosis, stage or subtype, genetic findings, and response to therapy.

CMML Prognosis:

- Generally, CMML has a more variable and less predictable natural history than CML.

- The disease may remain stable for years or gradually progress to acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

- Median survival typically ranges from 20 to 36 months after diagnosis, with younger patients and those eligible for stem cell transplantation having better prospects.

CML Prognosis:

- The outlook for CML patients has risen dramatically due to TKIs, with many achieving long-term remission.

- If detected and treated in the chronic phase, 5-year survival rates now exceed 80–90%.

- Progression to more advanced phases or resistance to TKIs portends a poorer outcome.

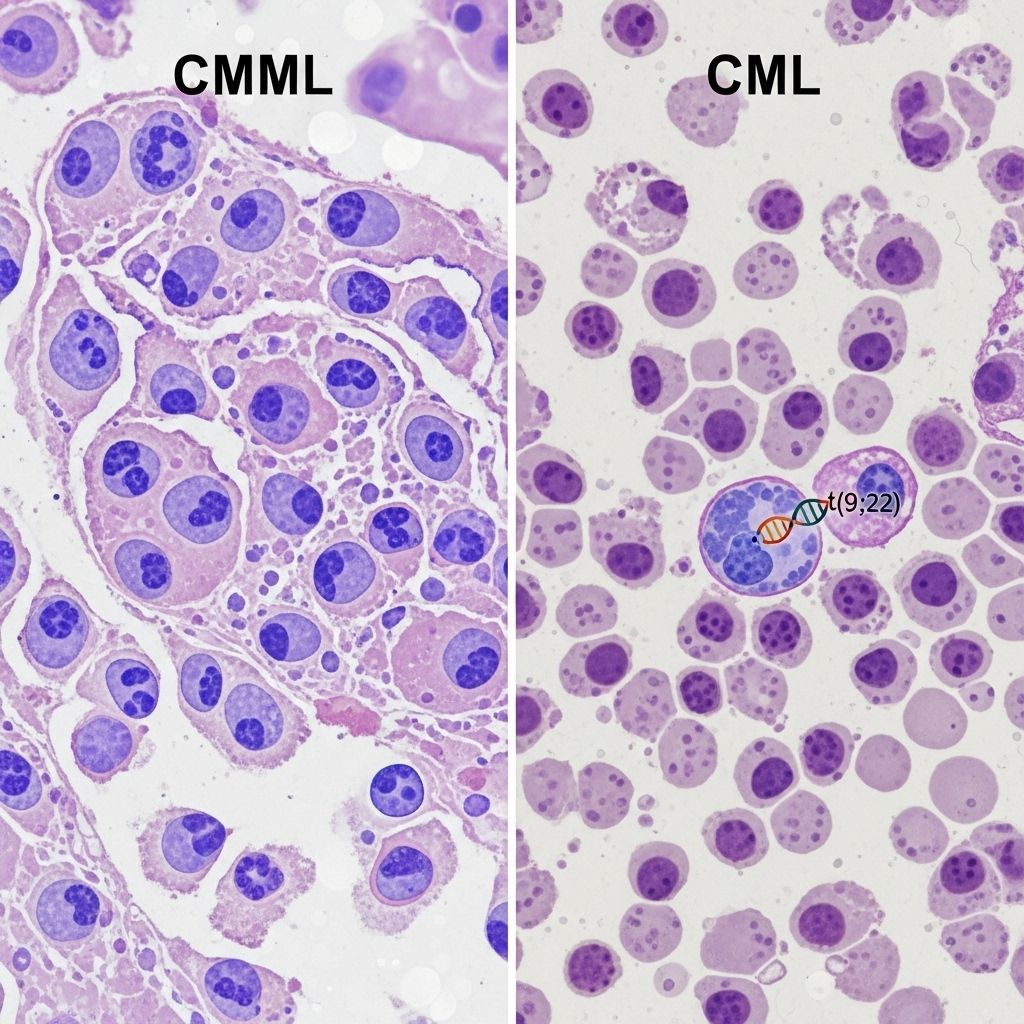

Diagnosis: How Are These Chronic Leukemias Distinguished?

The diagnosis of CMML vs. CML rests on a combination of laboratory techniques and clinical findings:

- Blood cell evaluation: Both diseases show high white cell counts, but CML predominantly affects granulocytes, while CMML has excessive monocytes.

- Genetic testing: The presence of the Philadelphia chromosome or BCR-ABL1 gene confirms CML; its absence (with other certain features) supports a diagnosis of CMML.

- Blast cell percentages: Used in both diseases to stage/severity and guide the choice of therapy.

- Clinical and morphologic findings: Bone marrow cell appearance under the microscope helps distinguish morphologic dysplasia (seen in CMML) from the nearly normal appearance (in CML).

Summary Table: CMML vs. CML At a Glance

| CMML | CML | |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Type Affected | Monocytes | Granulocytes |

| Chromosomal Abnormality | None specific (various acquired mutations) | Philadelphia chromosome (BCR-ABL1) |

| Classification | CMML-0, CMML-1, CMML-2 | Chronic, Accelerated, Blastic |

| Treatment Focus | Supportive care, chemo, transplant | TKIs, transplant, chemo |

| Prognosis | Variable (months–years) | Generally excellent (chronic phase, on TKIs) |

Potential Complications

- Transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in both diseases, though more common or rapid in some patients

- Anemia, bleeding, and frequent infections due to marrow failure

- Enlargement of spleen or liver due to abnormal cell buildup

- Side effects from treatments, including immunosuppression and transplant complications

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the Philadelphia chromosome, and how is it related to CML?

The Philadelphia chromosome is a genetic mutation resulting from a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22. This abnormality causes the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene, which leads to unchecked cell growth in CML. It is the defining marker for CML and is rarely (if ever) found in CMML.

Can CMML transform into CML?

No, CMML and CML are biologically distinct diseases. CMML may evolve into acute myeloid leukemia (AML), but it does not become CML.

Are there any age or risk factors linked to CML and CMML?

Both diseases are more common in older adults. There are rarely clear risk factors, although a history of other blood disorders or prior chemotherapy may raise the risk for certain individuals. Occasionally, family history plays a role, but most cases are sporadic.

Is a stem cell transplant always needed?

No, not all patients will need a stem cell transplant. In CML, most can live long, healthy lives on TKIs alone. In CMML, transplant is reserved for younger patients or those with aggressive disease due to its risks.

How often should follow-up testing or monitoring occur?

Regular follow-up is essential for both diseases. The schedule depends on type, treatment received, disease stage, and individual health factors. Monitor blood counts, disease markers, and treatment side effects as recommended by a hematologist-oncologist.

Takeaway Points

- CMML and CML are both chronic blood cancers but differ in the white blood cells they affect, their underlying genetics, their treatment options, and their prognosis.

- Expert evaluation—including lab tests, bone marrow assessment, and genetic testing—is essential for an accurate diagnosis.

- Modern therapies, especially TKIs for CML, have greatly improved survival and quality of life for many patients.

- CMML remains a challenging condition that may need individualized and supportive management.

Further Resources

- Hematologist-oncologist consultations for those diagnosed with leukemia

- Patient advocacy organizations, such as the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society

- Up-to-date research and clinical trial opportunities for both CMML and CML

References

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/cml-vs-cmml

- https://www.healthline.com/health/leukemia/cmml-vs-cml

- https://www.leukaemia.org.au/blood-cancer/types-of-blood-cancer/myelodysplastic-syndromes/chronic-myelomonocytic-leukaemia/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10319893/

- https://leukemiarf.org/leukemia/chronic-myelomonocytic-leukemia/

- https://www.droracle.ai/articles/106512/cml-versus-cmml

- https://www.myleukemiateam.com/resources/chronic-myelomonocytic-leukemia-an-overview

- https://www.mdanderson.org/cancer-types/leukemia.html

Read full bio of medha deb