Cerebral Fluid Shunts: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Care for Hydrocephalus

A comprehensive guide to cerebral shunts: understanding, placement, complications, and long-term management for hydrocephalus patients.

Cerebral shunts are life-saving medical devices used to manage hydrocephalus—a condition defined by an abnormal buildup of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the brain’s ventricles. Excess CSF increases intracranial pressure, risking brain tissue damage and life-threatening complications. Modern shunt systems help drain this excess fluid safely from the brain to other parts of the body, markedly improving quality of life and prognosis for affected patients. This article serves as a comprehensive guide to cerebral shunt purpose, surgery, daily management, and problem troubleshooting, empowering patients and caregivers with essential knowledge on hydrocephalus care.

What Is a Cerebral Shunt?

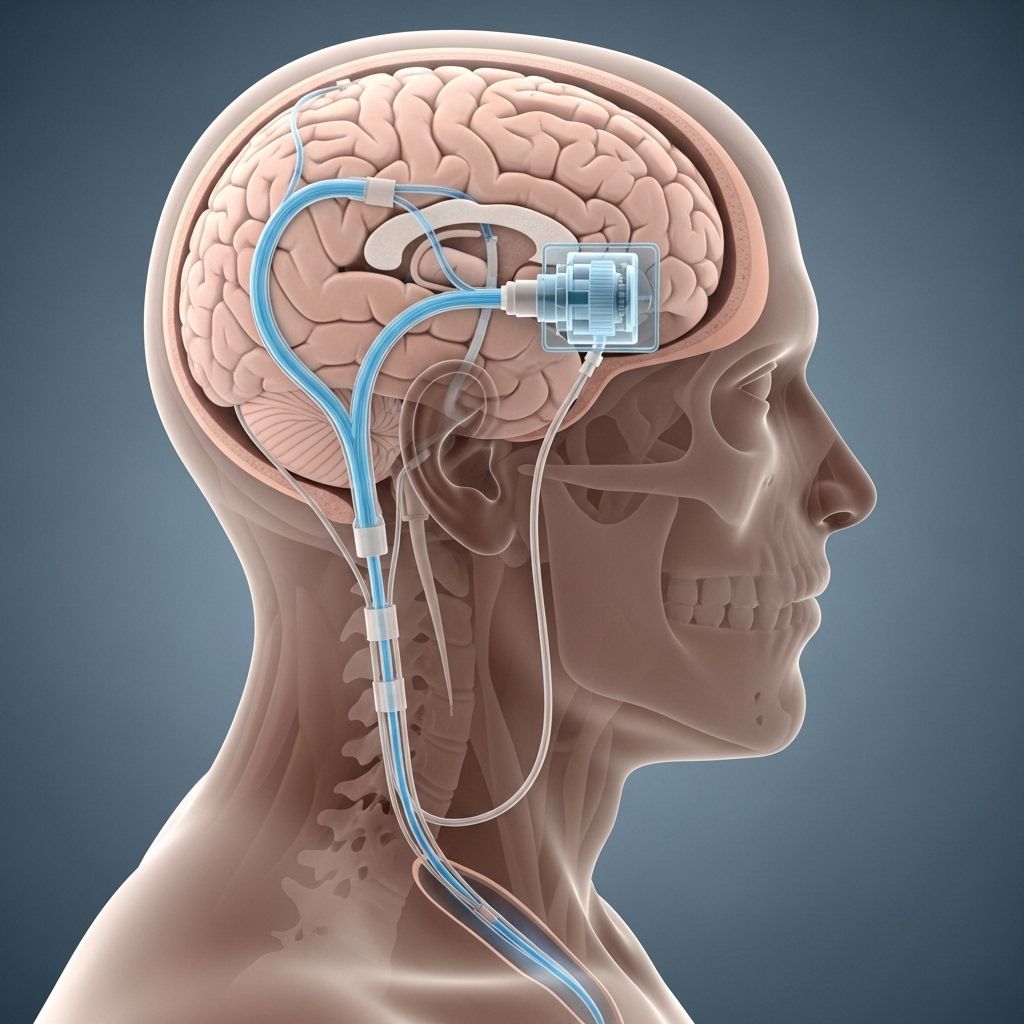

A cerebral shunt is a surgically implanted device composed of flexible tubing and a valve system. The device reroutes excess CSF from the brain’s ventricles to another body cavity (commonly the abdomen) where the fluid is safely reabsorbed. By regulating CSF flow and pressure, cerebral shunts prevent complications and control the symptoms associated with hydrocephalus.

Key Purposes of a Cerebral Shunt

- Reduces intracranial pressure caused by CSF accumulation.

- Prevents or minimizes damage to brain tissue due to prolonged pressure.

- Improves neurological function and reduces symptoms such as headaches, gait disturbance, and cognitive issues.

Types of Shunts and Valve Systems

Shunt systems come in different configurations, tailored to each patient’s needs and age. The core design involves three major components: the proximal (ventricular) catheter, a valve, and the distal catheter. Variations are based on the fluid’s outflow destination and valve technology used.

Major Shunt Types

- Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) Shunt: Channels CSF from the brain’s ventricles to the peritoneal (abdominal) cavity, the most commonly used type.

- Ventriculoatrial (VA) Shunt: Reroutes CSF into the right atrium of the heart, used when abdominal placement is not possible or contraindicated.

- Ventriculopleural Shunt: Drains CSF into the pleural cavity (around the lungs), typically reserved for patients unable to have peritoneal or atrial placement.

Valve Technologies

- Fixed-pressure valves: Operate at a pre-set pressure and are simple but less adaptable to patient changes.

- Programmable (adjustable) valves: Can be externally adjusted postoperatively to optimize drainage and minimize complications.

- Anti-siphon devices: Designed to reduce overdrainage risks by reacting to patient position changes and pressure differences.

Who Needs a Cerebral Shunt?

Shunts are indicated for individuals diagnosed with hydrocephalus due to various causes:

- Congenital hydrocephalus (present at birth)

- Acquired hydrocephalus from head injury, brain tumors, infection, or bleeding

- Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) most common in older adults, characterized by gait disturbance, urinary incontinence, and cognitive decline

Clinical evaluation, brain imaging, and sometimes lumbar punctures are employed to confirm the diagnosis and assess for surgical candidacy. According to clinical studies, up to 60–70% of patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus show meaningful improvement following shunt surgery.

The Shunt Placement Procedure

Shunt surgery is typically performed under general anesthesia by a neurosurgeon and includes several carefully coordinated steps:

- Incision and Access: A small incision is made on the scalp, and a burr hole is created in the skull to access the brain’s ventricles.

- Placement of the Ventricular Catheter: The proximal catheter is inserted into a lateral ventricle to allow CSF drainage.

- Valve Connection: The catheter is connected to a pressure-regulating valve, often positioned just behind the ear beneath the scalp.

- Routing the Distal Catheter: The distal catheter is tunneled subcutaneously (under the skin), leading to the fluid’s destination site (usually the abdomen).

- Closure and Recovery: The incisions are closed, and the patient is monitored in the recovery area or intensive care unit.

Surgical Considerations and Risks

- Shunt placement typically takes between one and two hours.

- Risks of surgery include bleeding, infection, or inadvertent damage to the brain or other tissues.

- Advanced imaging guidance and modern valve systems have improved placement accuracy and safety.

Postoperative Care and Hospital Stay

The initial recovery period after shunt surgery is vital for detecting early complications and ensuring proper device function:

- Hospital stay can range from 2 to 7 days, depending on patient age, underlying condition, and presence of complications.

- Postoperative imaging may be used to confirm catheter position and monitor for complications.

- Pain management, wound care, and early mobility are emphasized to reduce post-surgical risks.

Return to Activities

- Limited activity is usually recommended for the first few weeks after surgery.

- Most patients can gradually return to school, work, or normal physical activities after an initial recovery period, guided by their healthcare team.

Potential Complications of Cerebral Shunts

While shunt systems are crucial in treating hydrocephalus, they are not free from complications. Recognizing and addressing problems promptly is key to preventing serious outcomes.

Common Shunt Complications

- Shunt Infection: Can occur within months of placement or later, often presenting with fever, redness, tenderness along the shunt tract, nausea, or changes in neurological status.

- Shunt Malfunction or Obstruction: Blockages may form in any part of the shunt system, causing CSF buildup to recur with symptoms such as headache, vomiting, lethargy, altered consciousness, or vision changes.

- Overdrainage: Occurs when CSF drains too quickly, risking headache (especially in upright posture), subdural hematomas (bleeding around the brain), or slit ventricle syndrome.

- Underdrainage: Happens when CSF removal is inadequate, allowing hydrocephalus symptoms to persist or return.

- Mechanical Failure: Tubing disconnections, fractures, or valve misfunction can occur over time due to device aging or trauma.

Clinical Warning Signs of Shunt Problems

- Persistent or severe headache

- Vomiting or nausea unrelated to other illness

- Changes in vision or double vision

- Irritability, drowsiness, confusion, or other neurological changes

- Seizures (rare but possible)

- Redness, swelling, or discharge along the shunt tract

- Abdominal pain (in peritoneal shunts)

Diagnosing Shunt Malfunction

Because the symptoms of shunt problems can mimic other common illnesses, prompt and accurate diagnosis is critical. A variety of tests and technologies are employed to evaluate shunt function:

Diagnostic Approaches

- Physical and Neurological Examination: The clinician checks for classic hydrocephalus symptoms and signs of increased intracranial pressure.

- Neuroimaging: CT scans or MRI of the brain are commonly performed to evaluate ventricle size and shunt position.

- Shunt Series X-rays: Sequential X-rays may be taken along the shunt pathway to detect disconnections or kinks.

- Shunt Taps: In some cases, fluid may be withdrawn from a shunt access port for analysis.

- Innovative Non-Invasive Tools: Emerging technologies, such as non-radiative ultrasound devices, promise rapid bedside evaluation of shunt function without the need for invasive tests or radiation exposure.

Long-Term Outlook and Life with a Shunt

Most patients with shunts lead active, productive lives when provided with appropriate follow-up and preventive care. Regular checkups and patient education are important for timely detection of any issues.

Shunt Longevity and Maintenance

- While some shunts function for many years, most patients will require at least one revision surgery in their lifetime. Pediatric patients, in particular, may undergo multiple revisions as they grow.

- Technological advances, such as improved valve designs and anti-siphon devices, have reduced malfunction and overdrainage risks.

Patient Precautions and Lifestyle Considerations

- Activities such as swimming and most sports are generally permitted after surgical incisions have healed and with physician guidance. Contact sports may need to be avoided or undertaken with extra protective measures.

- MRI scans can usually be performed, but patients must inform radiology staff in advance if they have programmable valves so appropriate precautions (or reprogramming) can be arranged.

- Patients and families should wear a medical alert identification stating they have a shunt.

- Caregivers and patients must be alert to shunt problem symptoms and seek prompt medical attention if any arise.

Living Well with a Shunt: Support and Resources

Undergoing shunt placement and adapting to life with a device can be challenging. The support of a specialized care team, education, and resources help maximize long-term success.

- Regular neurosurgeon and neurology follow-ups help monitor shunt function and development over time.

- Hydrocephalus support groups and national organizations offer patient resources, advocacy, and connections to others with similar experiences.

- Family members, teachers, and caregivers play a vital role in observing symptoms and supporting young and older patients alike.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Cerebral Shunts

Q: How long does a cerebral shunt last?

A: Shunt longevity can vary widely—from years to decades. Most patients, especially children, will eventually require revision surgery as the body grows or if device complications arise.

Q: Is shunt surgery safe?

A: Shunt surgery is generally safe when performed by experienced neurosurgical teams. Like any operation, risks include infection, bleeding, or device malfunction, but modern techniques have made the procedure increasingly reliable.

Q: Can patients with shunts undergo MRI scans?

A: Yes, but it is important to inform staff beforehand. Some programmable valves require reconfiguration after MRI due to possible magnetic interference.

Q: What symptoms should prompt concern about shunt malfunction?

A: Severe or persistent headaches, vomiting, lethargy, changes in vision, seizures, or changes in mental status should prompt immediate medical evaluation.

Q: Are there activities patients with shunts cannot do?

A: Most everyday activities are possible. Some sports, including those with direct head contact, may require modifications or restrictions. Patients should discuss individual risks with their physician.

Key Resources and Patient Support

- Hydrocephalus Association: Information and support for patients and families.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine Neurology and Neurosurgery: Expert evaluation and long-term care for hydrocephalus and shunt management.

With ongoing advances in shunt design, diagnostic technology, and patient education, prognosis for patients with hydrocephalus continues to improve. Close collaboration among care teams, families, and patients ensures the best possible outcomes following cerebral shunt placement.

References

- https://www.jhuapl.edu/news/news-releases/150211-researchers-reduce-shunt-maintenance-hydrocephalus-patients

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9904195/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32521017/

- https://ventures.jhu.edu/news/brain-swelling-longeviti-cranial-implant-study/

- https://pure.johnshopkins.edu/en/publications/cerebrospinal-fluid-shunt-placement-for-pseudotumor-cerebri-assoc-3

Read full bio of Sneha Tete