Bicuspid Aortic Valve: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment, and Outlook

A detailed overview of bicuspid aortic valve, its causes, symptoms, potential complications, diagnosis, management, and treatment options.

Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) is a congenital heart condition that can impact the way the heart pumps blood to supply the body. Typically, the aortic valve has three flaps or ‘cusps,’ but in people with BAV, there are only two. This structural difference can lead to complications over time, especially as the valve ages. Understanding BAV’s causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and management is essential for those affected and their families.

Overview

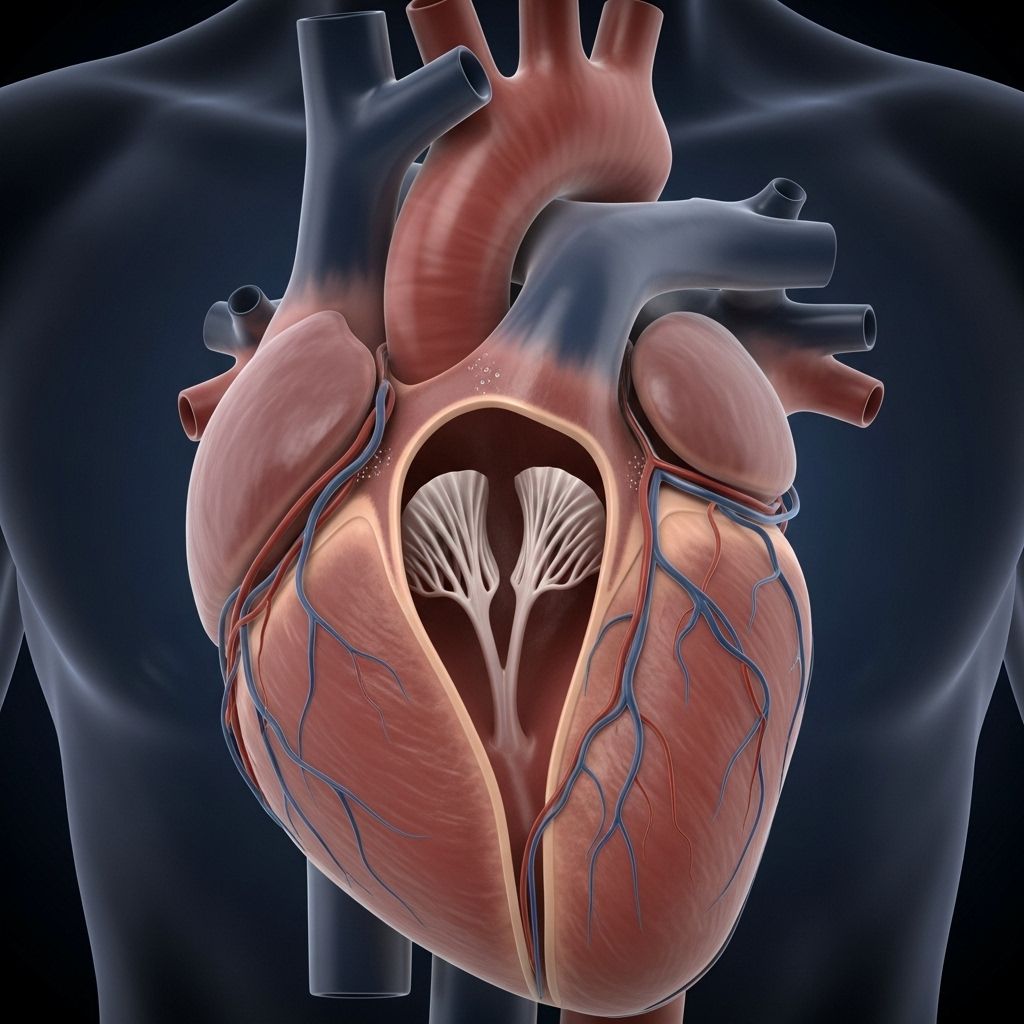

The heart has four main valves, each acting as gates to control blood flow in the proper direction. The aortic valve sits between the heart’s left ventricle and the aorta—the main artery carrying oxygen-rich blood to the body. In a typical heart, the aortic valve has three thin, mobile leaflets (tricuspid configuration) that open and shut with each heartbeat. A bicuspid aortic valve has only two leaflets, a condition present at birth. This altered anatomy can compromise the smooth flow of blood out of the heart and over time may result in significant cardiac problems.

How Does the Aortic Valve Work?

During each heartbeat, the aortic valve opens as the left ventricle contracts, allowing blood to flow from the heart into the aorta. The valve then closes tightly during relaxation to prevent blood from leaking back into the heart.

- With three leaflets (normal), blood flows efficiently out, and the valve closes securely.

- With two leaflets (bicuspid), the valve may not open fully, making it harder for the heart to pump blood (called aortic stenosis), or may not close properly, allowing blood to leak back (called aortic regurgitation).

Causes

Bicuspid aortic valve is a congenital condition—meaning it occurs during fetal development and is present at birth. The exact cause is not fully understood but is believed to involve complex genetic factors, possibly related to how connective tissue forms during embryonic growth. BAV tends to run in families, so children and siblings of those diagnosed with the condition have a higher risk.

- BAV is heritable; family screening may be recommended.

- No environmental factor has been convincingly linked to increased risk.

Symptoms

Many individuals with a bicuspid aortic valve have no symptoms for years, especially during childhood or early adulthood. As the condition progresses or complications develop, symptoms may emerge, typically in midlife (ages 50–70).

- Chest pain or tightness

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath—especially during exertion

- Lightheadedness or fainting (syncope)

- Swelling in the legs, ankles, or feet

- Heart murmur—often the first sign, detected by a physician listening with a stethoscope

Children and young adults with BAV usually have no symptoms unless complications arise early.

Complications

Having a bicuspid aortic valve increases the risk of specific heart and aorta-related complications:

- Aortic valve stenosis — Valve narrowing reducing blood flow from the heart; most common and typically emerges later in life.

- Aortic regurgitation — The valve doesn’t close properly, causing blood to flow backward into the heart.

- Enlarged aorta (aortopathy) — The aorta can widen or weaken, increasing the risk for aortic aneurysm or aortic dissection.

- Heart failure — The extra workload can weaken the heart muscle over time.

- Infective endocarditis — The misshapen valve is at higher risk of infection involving the heart’s lining or valve tissue.

Uncommon, but serious complications may include problems with the coronary arteries or unstable high blood pressure in the chest region.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis frequently follows the detection of a suspicious heart murmur or related symptoms during a routine physical exam. Confirming a diagnosis involves specialized imaging and tests:

- Echocardiogram (Echo) — An ultrasound of the heart that shows the structure and function of the valves, and identifies BAV as well as the presence of stenosis or regurgitation.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) — Records the electrical impulses and looks for associated abnormalities.

- Cardiac MRI or CT scan — May be ordered to evaluate the size of the aorta, especially if dilation or aneurysm is suspected.

- Chest X-ray — Can help assess the overall heart size and aorta shape.

- Genetic and family screening — Recommended if there’s a family history of BAV or aortic disease.

Routine checkups are vital. Often, mild cases are observed over time, while more severe forms need prompt intervention.

Treatment

The management of BAV is individualized based on severity and complications. Some people may never need intervention, while others require surgery.

Medical Treatment

- Medications:

- Blood pressure-lowering drugs

- Diuretics to reduce fluid buildup

- Drugs to control heart rhythm and workload

- Monitoring: Regular follow-up with echocardiograms to check for changes in valve or aorta function and structure.

Procedural and Surgical Treatments

- Balloon valvuloplasty — A catheter with a balloon is inserted, inflated to widen a stenotic valve (less common, usually reserved for certain populations or temporary relief).

- Surgical valve repair — Repair of the native valve to improve function, suitable for selected cases.

- Valve replacement surgery — Replacement with a mechanical or tissue valve is often required for severe stenosis or regurgitation.

- Aortic repair — If the aorta is significantly dilated, surgical repair or replacement of the affected segment may be necessary, often performed alongside valve surgery.

Modern surgical and interventional techniques are generally safe, and most individuals recover well, resuming normal lives with ongoing medical follow-up.

Management and Lifestyle

People with BAV should be managed by a healthcare team with experience in structural heart disease. Lifestyle adaptations play a key role in long-term outcomes:

- Regular exercise — Moderate, heart-healthy activity (limit if advised by your cardiologist).

- Heart-healthy diet — Low in saturated fats, refined sugars, and sodium; high in fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains.

- Blood pressure control — Essential to reduce stress on the heart and aorta.

- Avoid smoking and excessive alcohol — Cardiovascular risk factors worsen BAV prognosis.

- Infective endocarditis prevention — Good dental hygiene; prophylactic antibiotics before certain dental or surgical procedures if recommended by your doctor.

Annual or biannual visits to a cardiologist with echocardiographic monitoring are generally advised.

Outlook

Many people with a bicuspid aortic valve live normal, productive lives. Prognosis depends on the presence and management of complications such as aortic stenosis, regurgitation, or aortic dilation. Advances in valve repair and replacement techniques have dramatically improved long-term survival and quality of life for symptomatic individuals.

- Routine monitoring and early intervention are the keys to good outcomes.

- Genetic counseling and screening may benefit family members.

- Successful valve or aorta surgery can often restore a high level of function and activity.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What causes a bicuspid aortic valve?

Bicuspid aortic valve is a congenital (present at birth) condition thought to be caused by genetic factors that affect the development of the heart valves during fetal life.

How common is bicuspid aortic valve?

It is the most common congenital heart defect, affecting about 0.5–2% of the population.

What are the risks of a bicuspid aortic valve?

The main risks include aortic valve narrowing (stenosis), backward leaking (regurgitation), aortic enlargement (aortopathy or aneurysm), and the potential for valve infection (endocarditis).

Can you exercise with a bicuspid aortic valve?

Most people can exercise, but intensity and activity level recommendations depend on the severity of valve dysfunction and aorta size. Your cardiologist will guide you.

Are family members at risk?

Yes, BAV is heritable. First-degree relatives should inquire about screening, especially if someone in the family is diagnosed.

What is the life expectancy?

With appropriate monitoring, early intervention for complications, and good heart health management, many people with BAV enjoy a normal lifespan.

Summary Table: Bicuspid vs. Tricuspid Aortic Valve

| Feature | Bicuspid Aortic Valve | Tricuspid Aortic Valve |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Leaflets | 2 | 3 |

| Incidence | 0.5–2% (most common congenital defect) | Most of the population |

| Risk of Stenosis/Regurgitation | Much higher, particularly with age | Lower unless acquired valve disease |

| Associated Aortic Disease | Common (aneurysm, dissection) | Rare |

| Hereditary Risk | Yes | No |

Takeaway

Bicuspid aortic valve is a common heart valve congenital defect causing the valve between the left ventricle and aorta to have only two flaps instead of three. While many people may not be aware of their diagnosis for years, BAV increases the risk for serious heart complications, especially as they age. With proactive management, a healthy lifestyle, and, when necessary, surgical intervention, people with BAV can lead healthy, active lives. Genetic evaluation of family members is recommended due to the heritable nature of the condition. Always consult with a specialized cardiologist for personalized care and follow-up.

References

- https://www.healthline.com/health/heart-disease/bicuspid-aortic-valve

- https://marfan.org/conditions/bicuspid-aortic-valve/

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/bicuspid-aortic-valve/cdc-20385577

- https://www.healthline.com/health/heart/living-with-bicuspid-aortic-valve

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16780-bicuspid-aortic-valve-disease

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5141520/

- https://academic.oup.com/ehjcimaging/article/25/3/425/7420918

Read full bio of Sneha Tete