Atrial Septal Defect: Causes, Types, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Atrial septal defect is a congenital heart condition, often found in infants and children, defined by an abnormal hole between the heart’s upper chambers.

Atrial Septal Defect Overview

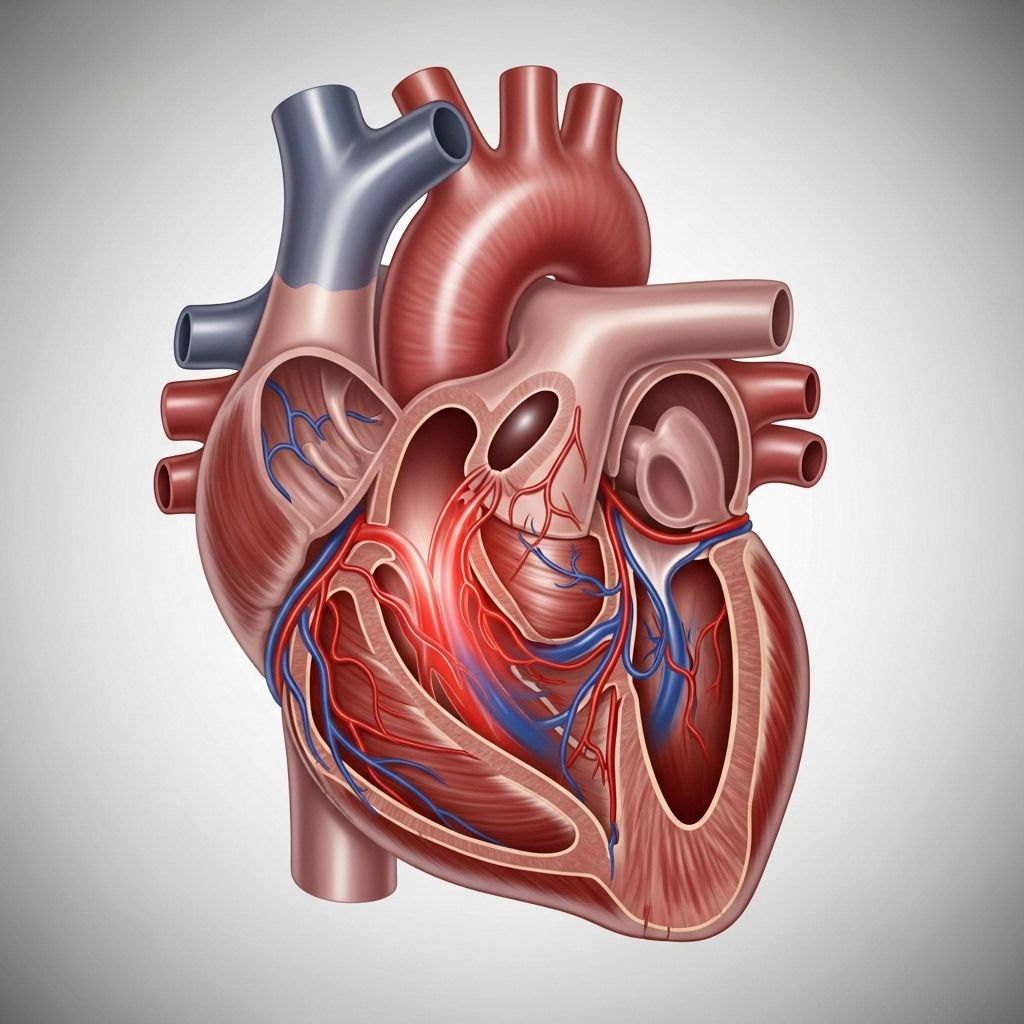

An atrial septal defect (ASD) is a congenital heart condition characterized by a hole in the wall (septum) that separates the heart’s two upper chambers (the atria). This opening disrupts normal blood flow through the heart, potentially leading to complications if untreated. ASDs are among the most common congenital heart defects, generally diagnosed in childhood and managed with considerable success by pediatric and adult cardiologists.

What Is an Atrial Septal Defect?

During fetal development, a natural opening exists between the atria to allow blood to bypass the lungs. This opening typically closes after birth. In children or adults with ASD, the opening persists or is abnormally large, allowing oxygen-rich blood from the left atrium to flow back into the right atrium. This increases the overall blood circulation to the lungs and can lead to several clinical signs and symptoms including heart murmurs and increased pressure in lung blood vessels .

- Location: The septum is the wall between the left and right atria; an ASD is a hole in this wall.

- Effect on circulation: Causes blood mixing between right and left sides, increasing lung blood flow.

- Symptoms: Many ASDs are “silent” early in life, but larger holes may cause murmurs or breathing difficulties.

Types of Atrial Septal Defects

Doctors categorize ASDs by their exact location and characteristics within the septal wall. Understanding these types is crucial for accurate diagnosis and treatment selection.

- Ostium Secundum Defect: Located in the middle part of the septum, and is the most common, accounting for about 75% of cases. This type is often amenable to catheter-based closure techniques .

- Ostium Primum Defect: Found in the lower part of the septum. This type comprises 15–20% of cases and is commonly associated with other heart defects, such as those seen in Down syndrome .

- Sinus Venosus Defect: In the upper part of the septum, often occurring alongside other structural heart changes. These are less likely to close on their own .

- Coronary Sinus Defect: The rarest, occurring where the wall separating the left atrium from the coronary sinus is missing or defective .

Causes and Risk Factors

Most cases of ASD are congenital, meaning they are present from birth. The exact cause is frequently unknown, but certain genetic and environmental factors are implicated.

- Genetic mutations: Identified in some families or patients, including conditions like Down syndrome or Ellis-van Creveld syndrome, which predispose to specific ASD subtypes .

- Environmental exposures: Certain chemicals encountered in utero may increase the risk of ASD formation, possibly by interacting with genetic susceptibilities .

- Normal fetal development: Every fetus has an opening between the atria, essential for pre-birth circulation, usually closing soon after birth. Failure to close, or an excessively large opening, leads to ASD .

Symptoms and Signs of ASD

Symptoms depend on the defect’s size, the volume of blood shunting between atria, and the direction of the blood flow.

- Small ASD: Often asymptomatic, may be discovered incidentally late in childhood or adulthood .

- Large ASD: Can lead to signs of heart or lung complications over time, including:

- Shortness of breath, especially with exercise.

- Frequent respiratory infections.

- Fatigue and poor weight gain (children).

- Heart murmur detectable during a physical exam.

- Swelling of legs, feet, or abdomen in severe cases.

Diagnosis of Atrial Septal Defect

Diagnosis typically involves a combination of clinical examination and cardiac imaging.

- Physical Exam: A heart murmur or abnormal heart sound often prompts further investigation in children.

- Echocardiogram: An ultrasound of the heart provides clear visualization of the ASD size, location, and effect on heart chambers.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): Helps assess heart rhythm and chamber enlargement.

- Chest X-ray: May show enlargement of the right atrium and ventricle, or increased lung vascularity if blood flow is excessive.

- Cardiac MRI/CT: Used for complex cases or when additional anatomical information is needed.

Severity and Potential Complications

The impact and seriousness of ASD depend heavily on several factors:

- Size of the defect: Holes smaller than 5 millimeters (< 0.2 inches) often close spontaneously within the first year. Defects greater than 1 centimeter (> 0.4 inches) generally persist and require intervention .

- Volume and direction of blood shunting: Excessive left-to-right flow increases workload on the right heart and lung vessels, potentially leading to pulmonary hypertension or heart failure if untreated .

- Associated heart problems: Other congenital heart defects compound risk and may trigger early symptoms .

Long-term complications from untreated ASD can include:

- Pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure in the lung vessels).

- Heart rhythm problems (arrhythmias).

- Stroke due to abnormal blood flow and clot formation.

- Right-sided heart enlargement or failure.

Treatment Options for ASD

Half of all ASDs may resolve naturally without intervention. Larger or persistent defects often require medical or surgical treatment .

Watchful Waiting

Doctors may recommend “watchful waiting” for small ASDs discovered during infancy. In these cases, periodic follow-up exams and echocardiograms are used to track progress. Some children may receive medications to manage symptoms, reduce fluid overload, or support heart function during this period .

Cardiac Catheterization

This minimally invasive procedure is the preferred treatment for many ostium secundum defects. Under sedation, a cardiologist threads a thin, flexible tube (catheter) through a blood vessel in the leg or neck to the heart and deploys a device to close the hole. Recovery is quicker than with open heart surgery, and risks are generally lower, but this option is not suitable for all types of defects .

- Advantages: Short recovery, less pain, lower risk of infection.

- Limitations: Only suitable for centrally located secundum ASDs.

Open Heart Surgery

Open surgery is recommended when the ASD is large, complex, or located in a region not accessible by catheter. Surgery is performed under general anesthesia, often in early childhood if the defect does not close naturally or causes symptoms .

- Incision: Performed through the chest.

- Repair: The surgeon closes the defect directly or places a patch over the opening.

- Risks: Include bleeding, infection, and complications related to anesthesia, but outcomes are generally excellent with modern techniques.

Outlook and Prognosis

Children and adults with appropriately treated ASD typically enjoy healthy, active lives. Untreated large ASDs, however, may result in serious cardiac complications later in life. Post-procedural follow-up is important to monitor for residual or recurrent defects, arrhythmias, or other heart issues. Most ASDs diagnosed and managed early have a favorable prognosis .

| ASD Type | Closure Potential | Usual Treatment | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ostium Secundum | May close on its own | Catheterization or open surgery | ~75% |

| Ostium Primum | Rarely closes on its own | Open surgery | 15–20% |

| Sinus Venosus | Rarely closes on its own | Open surgery | Rare |

| Coronary Sinus | Rarely closes on its own | Open surgery | Very rare |

Prevention and Genetic Counseling

Because most ASDs arise for unknown reasons, routine prevention is not generally possible. Maternal health during pregnancy—including good nutrition, avoidance of harmful substances, and management of chronic diseases—may reduce risk. Families with histories of congenital heart disease may benefit from genetic counseling, especially prior to future pregnancies.

Living with ASD: Support and Monitoring

- Routine follow-up with a cardiologist is essential for children and adults who have undergone closure procedures or surgery.

- Activity restrictions are rarely needed after successful ASD closure.

- Life expectancy is normal for most people with treated ASD.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Is ASD the same as a heart murmur?

A: No. ASD can cause a heart murmur, which is a sound created by abnormal blood flow through the heart, but the murmur itself is a sign—not the condition.

Q: Can an atrial septal defect close on its own?

A: Small ASDs often close spontaneously during the first year of life. Larger or certain types generally require intervention.

Q: Do adults get diagnosed with ASD?

A: Yes. Some ASDs remain undetected until adulthood, especially if small or asymptomatic.

Q: Will my child need surgery?

A: About half of all ASDs close without surgery. Persistent or symptomatic ASDs may require minimally invasive catheter closure or open surgery, depending on the defect type and size.

Q: What is the prognosis after ASD closure?

A: Prognosis is excellent for most children and adults after appropriate treatment. Routine monitoring ensures there are no further cardiac complications.

References

- https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000157.htm

- https://www.healthline.com/health/heart/atrial-septal-defects

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/atrial-septal-defect/symptoms-causes/syc-20369715

- https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/asd.html

- https://www.healthline.com/health/types-of-congenital-heart-disease

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535440/

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/11622-atrial-septal-defect-asd

- https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/congenital-heart-defects/about-congenital-heart-defects/atrial-septal-defect-asd

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6174151/

- https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circulationaha.105.592055

Read full bio of medha deb