Assessing Cardiovascular Risk with C-Reactive Protein (CRP)

Understanding why C-reactive protein (CRP) matters in evaluating heart disease risk, its testing methods, and limitations.

C-reactive protein (CRP) is an important biomarker produced by the liver in response to inflammation in the body. Over the past two decades, research has highlighted the potential role of CRP in assessing an individual’s risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, including heart attacks and strokes. This article explores the fundamentals of CRP, how it is measured, its connection to heart disease, and the limitations and considerations associated with its use in clinical practice.

What Is C-Reactive Protein (CRP)?

CRP is a protein that circulates in the blood and rises when there is systemic inflammation. Many conditions, such as infections or chronic inflammatory diseases, can cause elevated CRP. However, in recent years, researchers discovered that even low but persistently elevated levels of CRP may reflect underlying inflammation within blood vessels, providing insight into cardiovascular risk.

- Produced by the liver: CRP is manufactured primarily in the liver.

- Marker of inflammation: Elevated CRP levels are found in various conditions involving inflammation, including infections, autoimmune diseases (like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis), and tissue injury.

- Acute-phase reactant: CRP reacts rapidly and dramatically to increases in inflammation.

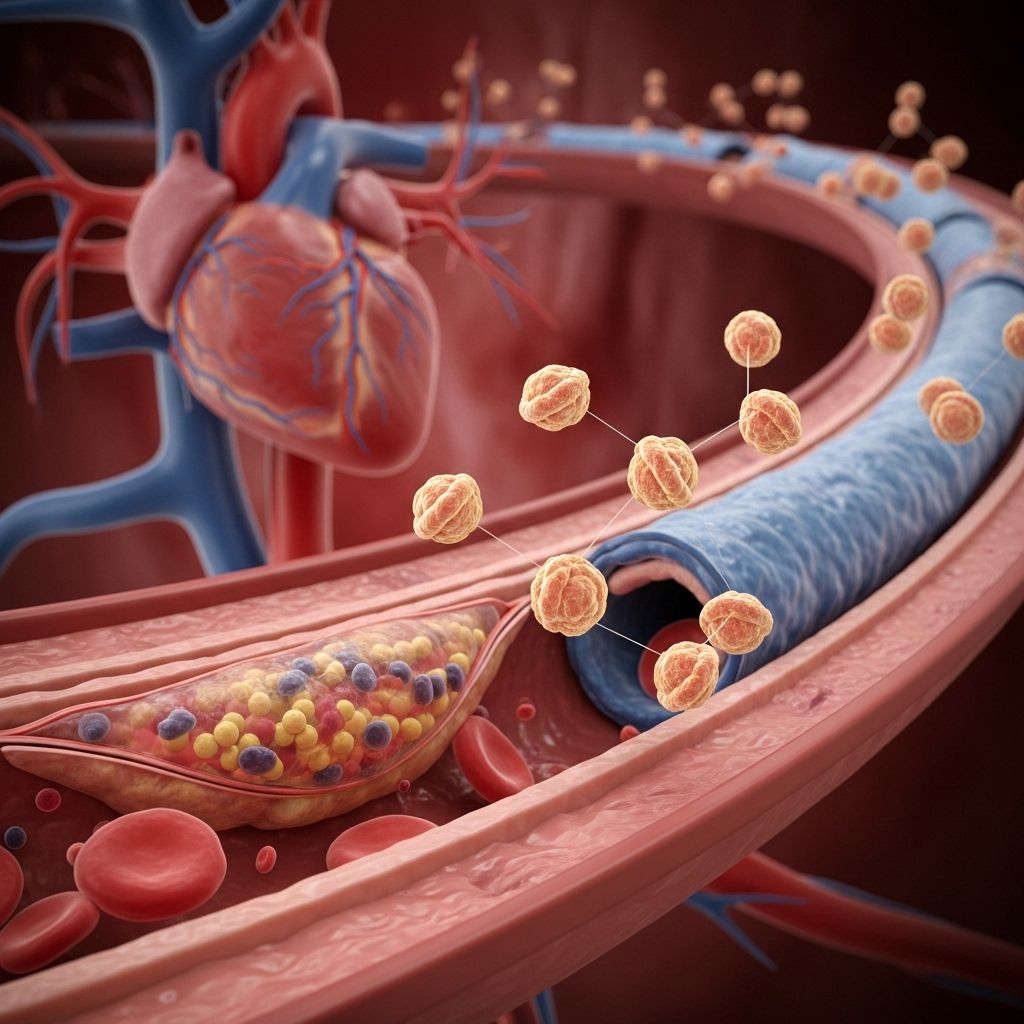

The Inflammatory Link to Cardiovascular Disease

Classic cardiovascular risk factors, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, and smoking, do not explain all heart disease cases. Recent advances reveal that inflammation plays a central role in the development and progression of atherosclerosis—the buildup of fatty, inflammatory plaques inside arteries that can rupture and cause heart attacks or strokes.

Inflammation within the vessel walls contributes to:

- Formation of atherosclerotic plaques

- Plaque instability, making them prone to rupture

- Recruitment of immune cells, worsening arterial damage

Because CRP levels rise in response to systemic inflammation, scientists hypothesized and later demonstrated that higher CRP levels may indicate a greater risk for cardiovascular events even among people with otherwise normal cholesterol or blood pressure.

What Is a CRP Test?

The CRP test is a straightforward blood test that measures the level of C-reactive protein circulating in your body. The test is widely available and commonly used to assess inflammation for a variety of medical conditions.

- Standard CRP test: Detects higher levels of inflammation, such as those seen in infections or autoimmune diseases.

- High-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) test: Specifically designed to detect much lower levels of CRP. This version is sensitive enough to pick up subtle, chronic inflammation associated with atherogenesis (the early formation of artery plaques).

How Is the CRP Test Performed?

A health professional collects a sample of blood from a vein, usually in your arm. The analysis is performed in a laboratory, and results can often be reported within a day. For cardiovascular risk assessment, the high-sensitivity version is preferred because of its accuracy at lower CRP concentrations.

CRP Levels and Their Meaning

Interpretation of CRP results depends on the specific test used. For cardiovascular risk, only the hs-CRP values are informative. The American Heart Association and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have provided reference ranges for hs-CRP in the context of heart disease risk:

| hs-CRP Level (mg/L) | Cardiovascular Risk Category |

|---|---|

| < 1.0 | Low risk |

| 1.0 – 3.0 | Average (moderate) risk |

| > 3.0 | High risk |

For the most accurate assessment, the test is often repeated after about two weeks to confirm a persistent elevation. Single, isolated elevations can sometimes reflect acute illnesses, injuries, or other transient causes of inflammation rather than true underlying cardiovascular risk.

CRP vs. Traditional Heart Disease Risk Factors

Traditional risk assessments for cardiovascular disease focus on factors like age, sex, cholesterol levels, blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, and family history. Many experts questioned whether measuring CRP provides additional information beyond these established risks.

Key findings from various studies include:

- CRP can independently predict future cardiovascular events in some people, even when traditional risk factors are controlled for.

- Measuring both LDL cholesterol and CRP identifies more high-risk individuals than either marker alone. For example, some people with low LDL but high CRP have a significant risk of heart disease, which would be missed if only cholesterol was measured.

- However, other large-scale studies indicate that when all traditional risk factors are known and incorporated into risk calculation models (like the Framingham Risk Score), adding CRP does not significantly improve the ability to predict heart disease in the general population, particularly in the elderly.

When Is a CRP Test for Cardiovascular Risk Useful?

Based on extensive research and guidelines, the high-sensitivity CRP test should be considered mainly for people at intermediate risk (roughly 10%-20% risk of cardiac event within the next 10 years).

- For those at low risk, testing rarely changes management.

- For those at already high risk, aggressive risk factor modification is recommended regardless of CRP level.

- Testing is most helpful when the decision to start or intensify preventive therapies (like statins) is unclear based on traditional risk factors alone.

How Accurate Is CRP in Predicting Heart Disease?

CRP reflects inflammation, which is an indirect marker of atherosclerotic activity. Some individuals may have elevated CRP from non-cardiac causes, including infections, trauma, or chronic inflammatory illnesses. As a result, CRP should not be used as a standalone test for heart disease risk. It is most informative when interpreted in the context of a full clinical evaluation, including cholesterol levels and other risk factors.

Major points about accuracy:

- A persistently elevated hs-CRP (above 3 mg/L on repeated tests, with no other explanation) suggests a higher risk of cardiovascular events.

- The test is not specific: other causes of inflammation must be ruled out before attributing risk to the cardiovascular system.

Should Everyone Get a CRP Test?

Major medical organizations recommend against routine hs-CRP screening of all adults. Instead:

- Intermediate-risk individuals: Testing may help clarify risk and inform shared decision-making about preventive therapies.

- Low or high-risk individuals: Routine testing usually does not change management or outcome.

- Discuss your overall risk profile and possible benefits of CRP testing with your healthcare provider.

How to Lower High CRP and Reduce Cardiovascular Risk

Lowering CRP is not a direct treatment goal, but reducing underlying inflammation and atherosclerosis will improve both CRP levels and cardiovascular risk.

Main approaches include:

- Adopting a heart-healthy diet: Emphasize fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats; limit saturated fat and processed foods.

- Engaging in regular physical activity: Aim for at least 150 minutes per week of moderate exercise.

- Avoiding tobacco: Smoking cessation is critical.

- Managing weight: Achieving and maintaining a healthy weight helps reduce CRP and cardiovascular risk.

- Controlling cholesterol, blood pressure, and diabetes: Medications and lifestyle changes that address these factors may also lower CRP.

- Statins: These cholesterol-lowering medications also appear to lower CRP levels and reduce the risk of heart attack even in people without high cholesterol.

Limitations of the CRP Test

While measurements of hs-CRP provide valuable insight, the test itself has several limitations:

- Lack of specificity: Elevated CRP is not specific to cardiovascular inflammation; results may be elevated for many other reasons.

- Variability: CRP levels can fluctuate due to temporary illness, injury, or other changes in health status. Repeat testing may be needed for accurate assessment.

- Not a replacement: CRP testing does not replace traditional risk factor evaluation. Managing cholesterol, blood pressure, blood sugar, and lifestyle remains the cornerstone of prevention.

- Age and sex: Reference ranges and risk interpretation may vary among different demographic groups.

Summary Table: CRP and Cardiovascular Risk

| Factor | Significance |

|---|---|

| High-sensitivity CRP level | Marker of low-grade inflammation and cardiovascular risk |

| Persistent elevation (>3 mg/L) | Increased risk of heart attack or stroke, especially when other causes of inflammation are excluded |

| Single elevation | May reflect transient issues (infection, injury); often re-test is necessary |

| CRP and LDL measurement together | Identifies high-risk individuals that might be missed by measuring either alone |

| Testing populations | Most informative for those at intermediate risk of cardiovascular disease |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Is a high CRP result a diagnosis of heart disease?

A: No. Elevated CRP indicates inflammation but does not specify its source or mean you have heart disease. It must be interpreted along with clinical context and other risk factors.

Q: Can CRP levels be reduced naturally?

A: Yes. Lifestyle changes, including diet, exercise, and smoking cessation, along with medications to treat high cholesterol, blood pressure, or diabetes, can lower CRP and overall cardiovascular risk.

Q: Should everyone at risk have their CRP tested?

A: CRP testing is most useful for people at intermediate risk. Talk to your healthcare provider to determine if CRP testing may help clarify your risk assessment or guide treatment.

Q: Can a cold or infection raise my CRP?

A: Yes. Acute infections, injuries, and other illnesses can temporarily elevate CRP levels. Tests for cardiovascular risk should ideally be done when you are healthy, and sometimes repeated to confirm findings.

Q: How does CRP compare to cholesterol in predicting heart disease?

A: CRP and LDL cholesterol provide overlapping but distinct information. Using both together can identify more individuals at risk than either test alone. However, traditional risk factor management remains essential.

References

- van der Meer IM, de Maat MPM, Kiliaan AJ, et al. The Value of C-Reactive Protein in Cardiovascular Risk Prediction.

- WebMD. “C-Reactive Protein Test: What It Means to You.”

- PMC. “C-Reactive Protein: The Quintessential Marker of Systemic Inflammation.”

- Harvard Health. “C-Reactive Protein test to screen for heart disease.”

References

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/215672

- https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/c-reactive-protein-test

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10525787/

- https://www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/c-reactive-protein-test-to-screen-for-heart-disease

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/c-reactive-protein-test/about/pac-20385228

- https://www.labcorp.com/tests/120766/c-reactive-protein-crp-high-sensitivity-cardiac-risk-assessment

- https://www.uscjournal.com/articles/high-sensitivity-c-reactive-protein-atherosclerotic-cardiovascular-disease-measure-or-not?language_content_entity=en

Read full bio of medha deb