Anatomy of the Skin: Structure, Layers, and Essential Functions

Explore the complex structure, cellular makeup, and crucial protective functions of the human skin, the body's largest organ.

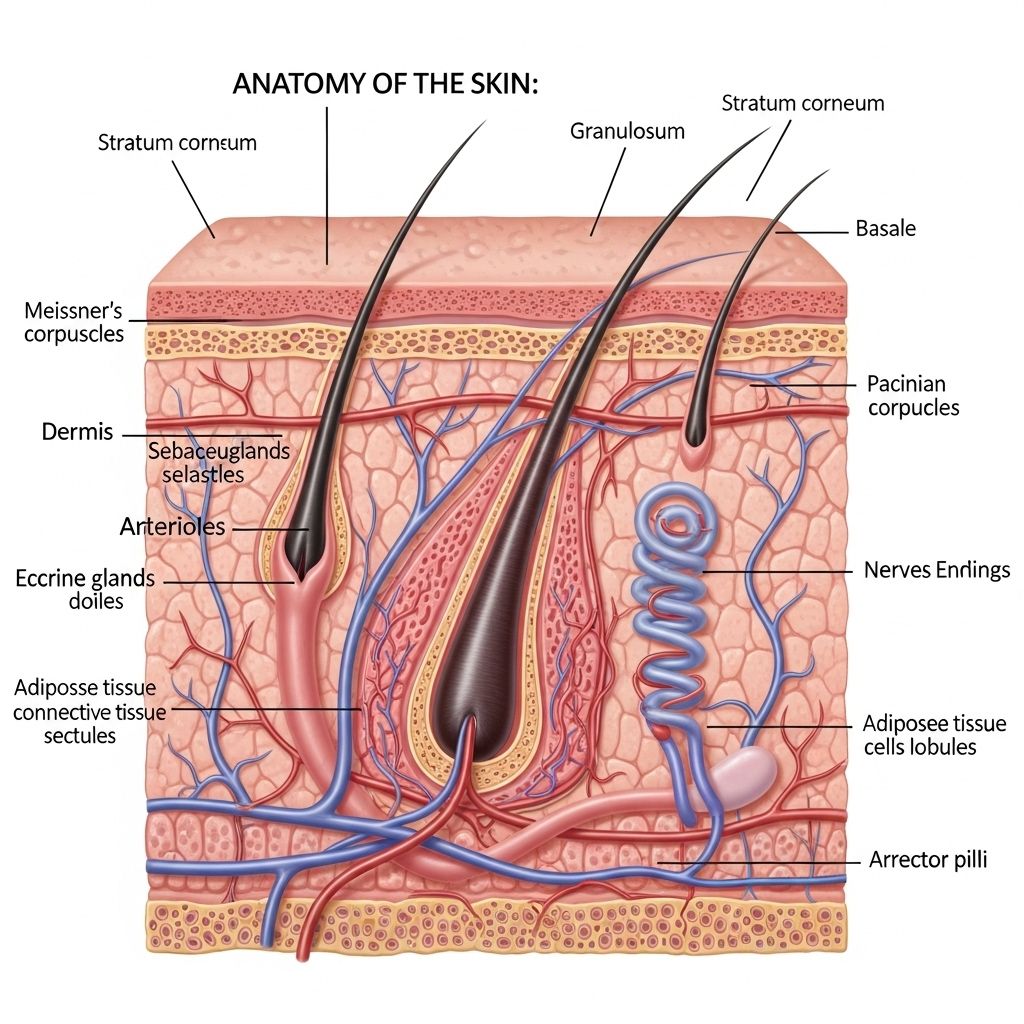

Anatomy of the Skin

The skin is the largest organ of the human body, accounting for roughly 16% of total body weight. As a multifunctional organ and the body’s outermost barrier, it is essential for protection, sensation, temperature regulation, and much more. Through its layered construction and specialized cells, the skin forms the foundation for the integumentary system, which also comprises hair, nails, sweat glands, and sebaceous (oil) glands.

Core Functions of the Skin

- Protection against pathogens, physical damage, and chemical irritants

- Temperature regulation through sweat secretion and blood vessel modulation

- Sensation via extensive neural receptors

- Vitamin D synthesis utilizing UVB sunlight absorption

- Water retention to prevent dehydration

Overview: Layers of the Skin

The skin features a sophisticated structure with three primary layers, each with distinctive functions and cellular makeup:

- Epidermis – the thin, outermost protective layer

- Dermis – the thicker, middle layer rich in nerves, blood vessels, and connective tissue

- Hypodermis (Subcutaneous Layer) – the deepest layer, comprised mainly of fat and connective tissue

Epidermis: The Protective Outer Layer

The epidermis is the outer shield of the body, made of stratified epithelial cells that continually renew. Despite its thinness, it provides formidable protection against mechanical injury, pathogens, and water loss. The epidermis contains multiple specialized cell types and is structured into distinct layers:

Key Cell Types in the Epidermis

- Keratinocytes – predominate; produce keratin and lipids for water barrier and structural integrity

- Melanocytes – produce melanin, which gives skin its pigmentation and absorbs harmful UV radiation

- Langerhans cells – immune function, capturing and presenting antigens

- Merkel cells – mechanical sensory receptors involved in touch detection

Structural Layers of the Epidermis

| Layer Name | Location | Main Features |

|---|---|---|

| Stratum Basale (Germinativum) | Deepest layer; adjacent to dermis | Mitotically active stem cells; site of keratinocyte and melanocyte origin |

| Stratum Spinosum (Prickle Cell Layer) | Above stratum basale | Keratinocytes connected by desmosomes; initial keratin production |

| Stratum Granulosum (Granular Layer) | Above stratum spinosum | 3–5 cell layers; contains keratohyalin and lamellar granules for keratin/adhesion and water barrier formation |

| Stratum Lucidum | Only present in thick skin (palms, soles) | Translucent layer of dead cells, providing extra protection |

| Stratum Corneum | Surface layer | 20–30 layers of dead, flattened, keratinized cells; main barrier against environment |

Thick vs Thin Skin

- Thick Skin – found on palms and soles; features all five layers, including the stratum lucidum

- Thin Skin – covers most of the body; lacks the stratum lucidum and generally has a thinner stratum corneum and other layers

As keratinocytes migrate from the stratum basale up through the layers, they mature and eventually become part of the stratum corneum. These cells are continuously shed and replaced, forming skin flakes or dandruff in routine turnover.

Dermis: The Supportive Middle Layer

Beneath the epidermis lies the dermis, significantly thicker and composed mainly of dense, fibrous connective tissue. It supports the epidermis structurally and functionally, housing blood vessels, lymphatics, nerve receptors, hair follicles, and skin glands.

Primary Dermal Layers

- Papillary Layer

• Superficial and thin; made of loose connective tissue.

• Contains finger-like projections (papillae) that interlock with the epidermis, enhancing structural stability and forming the basis of fingerprints.

• Rich in blood vessels, fibroblasts (making collagen), sensory nerve endings (e.g., Meissner corpuscles for fine touch, free nerve endings for pain), and immune cells (macrophages).

• Responsible for unique gripping surface and tactile sensitivity. - Reticular Layer

• Deeper and much thicker layer; composed of dense connective tissue.

• Packed with collagen and elastin fibers for strength and flexibility.

• Houses accessory structures, such as oil (sebaceous) glands, sweat glands, hair follicles, lymph vessels, and nerves.

Dermal Functions and Components

- Connective tissue matrix with collagen, fibronectin, hyaluronic acid, and elastin for mechanical support and resilience

- Blood and lymphatic vessels that nourish the epidermis and regulate immune responses

- Neural structures for touch, pressure, temperature, and pain sensation

- Small muscles (arrector pili) associated with hair follicles

Dermal fibroblasts actively secrete key proteins and molecules for healing and repair, illustrating the layer’s dynamism beyond simple support.

Hypodermis (Subcutaneous Layer): The Deep Anchoring Layer

The hypodermis, or subcutaneous tissue, forms the deepest layer of the skin. It acts as an anchor to underlying muscle while providing insulation, energy storage, and physical cushioning.

- Composed primarily of adipose (fat) tissue and connective fibers

- Protects deeper body structures from trauma and temperature extremes

- Permits skin movement and flexibility above bony or muscular regions

- Contains large blood vessels and nerves that branch up to serve the dermis

Accessory Structures of Skin

Several essential structures are embedded within the dermis and hypodermis, linking the skin’s anatomy to broader physiological roles:

- Hair follicles – produce and anchor hair shafts, contribute to warmth and sensation

- Sweat glands – regulate temperature via perspiration and facilitate excretion of some wastes

- Sebaceous (oil) glands – secrete sebum, which lubricates, waterproofs, and protects skin and hair

- Nails – protect fingertips and enhance fine motor control

The coordinated actions of these accessory organs enable the skin to function as a stable, adaptable barrier in diverse environmental conditions.

Major Functions of the Skin: A Closer Look

- Barrier to pathogens: Physical and biochemical barriers (keratin, lipids, defensins) shield against infection and injury.

- Thermoregulation: Evaporation of sweat, vasodilation, and vasoconstriction help regulate body temperature.

- Sensory reception: Specialized endings detect fine touch, pressure, vibration, temperature, and pain.

- Vitamin D synthesis: UVB-triggered reactions in the epidermis lead to vitamin D production, essential for bone health.

- Water management: Lipids and cell junctions prevent undue water loss and maintain hydration.

- Immune defense: Langerhans cells, macrophages, and other immune cells capture antigens and participate in initial immune responses.

- Identity and communication: Skin tone (melanin) and surface features (fingerprints) play roles in social interaction, identity, and forensic science.

Skin Types and Anatomical Variation

- Thick skin: Found on the palms and soles; adapted for high abrasion and mechanical stress.

- Thin skin: Covers most body surfaces; less robust and more flexible, with hair follicles present.

Skin thickness, the density of accessory organs, and pigmentation all vary regionally and between individuals, reflecting adaptation to environment, heritage, and health status.

Common Disorders and Changes in Skin Anatomy

- Aging – skin thins, loses elasticity (less collagen/elastin), and shows increased wrinkling, dryness, and vulnerability to injury.

- Injury and repair – wounds trigger complex healing processes involving all skin layers, fibroblasts, and immune components.

- Dermatitis – inflammation often involving the epidermis and dermis, can be triggered by irritants, allergens, or autoimmune reactions.

- Infections – bacteria, fungi, and viruses penetrate the skin’s defenses, causing specific diseases.

- Skin cancers – arise from mutations in skin cells, most commonly keratinocytes (carcinomas) or melanocytes (melanomas).

Skin Care and Maintenance

Healthy skin requires ongoing care to maintain its structure and function:

- Cleansing – removes oils, dirt, pathogens, and dead cells

- Moisturizing – preserves hydration, supports barrier repair

- UV protection – sunscreen and protective clothing minimize damage to cells and DNA

- Nutrition – supports cell growth, healing, and pigment production (including vitamin D synthesis)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the main function of the skin?

The skin acts as a protective barrier, regulating temperature, detecting sensory stimuli, and enabling vitamin D synthesis.

How many layers are in the skin?

The skin comprises three main layers: epidermis (outer), dermis (middle), and hypodermis (deepest).

What cells produce skin pigment?

Melanocytes, located in the stratum basale of the epidermis, synthesize melanin, the primary skin pigment.

Why are some areas of skin thicker than others?

Areas like the palms and soles have ‘thick skin’ with an extra stratum (stratum lucidum) for added protection against abrasion.

How does the skin heal after injury?

Skin repair involves coordinated activity of epidermal stem cells, dermal fibroblasts, immune cells, and vascular responses to regenerate damaged tissue.

References

- Information synthesized from authoritative medical sources including NCBI Bookshelf, Cambridge Media Journals, and educational videos.

References

Read full bio of Sneha Tete