Anatomy of the Breasts: Structure, Function, and Health

A comprehensive guide to the breast’s anatomy, its role in health and lactation, and common concerns for both women and men.

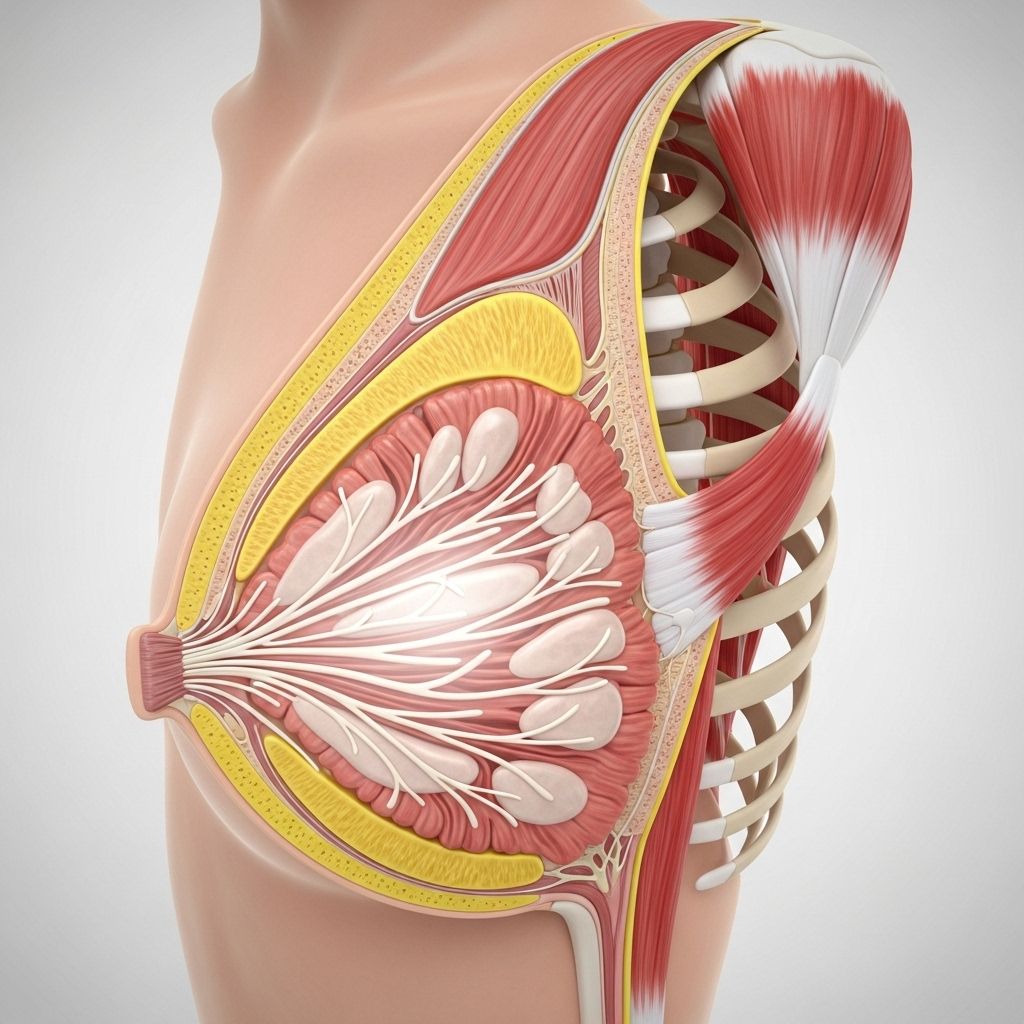

Anatomy of the Breasts

The breasts are complex, specialized organs on the chest—most notably developed in women but present in both sexes—to provide the crucial function of milk production for breast-feeding infants. Beyond their core role in lactation, the breasts are essential to both health and self-image. Knowing their anatomy is fundamental not only for understanding normal body function but also for recognizing changes and supporting breast health throughout life.

Location and Position

- Location: Each breast sits atop the pectoralis major chest muscle, covering the upper ribs.

- Horizontal Extent: Breasts extend horizontally from the edge of the sternum (the breastbone at the center of the chest) to the midaxillary line (which runs down the side of the underarm).

- Axillary Tail: The axillary tail of Spence is an extension of breast tissue into the underarm area, important as it can harbor breast pathologies.

- Vertical Position: Breasts typically span from the 2nd to the 6th rib, but their size and positioning can vary with age, genetics, and body type.

Structural Components of the Breast

The breast’s anatomy is intricate, with layers designed for structural support, milk production, and sensitivity. It consists of several major elements:

- Skin and Fascia: The outer surface is covered by skin, with a thin layer of connective tissue called fascia beneath. There is a superficial fascia just under the skin and a deep fascia sitting atop the pectoralis muscle. These envelop the core breast tissue and provide some support.

- Glandular (Milk-Producing) Tissue: The true functional portion, including lobes, lobules, and ducts.

- Stroma (Supportive Tissue): This refers to the combination of fibrous tissue and adipose tissue (fat) distributed among the glandular tissue. These impart the breast’s shape, volume, and feel.

- Ligaments: Cooper’s ligaments are fibrous bands running from the skin deep into the breast, attaching to the chest muscle fascia and maintaining breast structure.

Nipple and Areola

- Nipple: A protruding structure at the breast’s center, providing an outlet for milk. It contains multiple small openings for milk ducts and is rich in nerve endings.

- Areola: The pigmented circular area surrounding the nipple. It has specialized glands (Montgomery glands) that secrete oils to lubricate and protect the skin during breastfeeding.

- Together, the nipple and areola make up the nipple-areola complex, essential both anatomically and in surgical and imaging procedures.

Glandular Structures: Lobes, Lobules, and Ducts

The true functional core of the breast lies in its epithelial (glandular) component, which supports the production and delivery of milk:

- Each breast contains between 15 to 20 lobes arranged in a flower-petal pattern around the nipple.

- Each lobe contains smaller units called lobules, which in turn consist of the milk-producing alveoli.

- Ducts lead from the lobules toward the nipple, widening into lactiferous sinuses near the areola before narrowing again to pass through the nipple’s surface.

- The terminal intersection of each terminal duct and its associated lobule is known as the terminal ductal lobular unit (TDLU). Most breast cancers originate from the TDLUs.

Table: Major Glandular Components in the Breast

| Component | Function | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Lobe | Main unit for milk grouping | 15–20 per breast. Each contains many lobules. |

| Lobule | Milk production | Clusters of alveoli produce and secrete milk. |

| Duct (Milk duct) | Transport | Carries milk from lobule to nipple; widens in areola region (lactiferous sinus). |

| TDLU | Cancer origin | Junction of terminal duct and lobule; most susceptible to carcinogenesis. |

Stroma: Supportive Tissue of the Breast

The stroma is the matrix within which the glandular elements are suspended, providing both structural support and defining the overall size, texture, and resiliency of the breast.

- Adipose Tissue: Fat cells that largely determine the breast’s size and shape; radiolucent on imaging.

- Dense Fibrous Tissue: Thick connective fibers, more prevalent in younger women, responsible for firmness; appears denser (whiter) on imaging scans.

- Regions of Stroma:

- Subcutaneous: Just beneath the skin, between superficial fascia and the gland.

- Intraparenchymal: Among the lobes and lobules.

- Retromammary: Behind the gland, adjacent to the deep fascia.

- Cooper’s Ligaments: Tough fibrous bands providing internal support; their stretching or weakening over time leads to breast sagging.

Lymphatic System of the Breast

The lymphatic system plays a pivotal role in the breast’s immune defense and is central to the spread (or containment) of diseases such as breast cancer.

- Superficial lymphatic capillary network originates in the skin and areola, merging into precollectors and lymph collectors deeper in the tissue.

- Subareolar plexus: Dense web of lymphatic vessels underneath the nipple-areola complex, draining much of the superficial breast tissue.

- Main drainage pathways:

- Axillary lymph nodes: Primary route for lymphatic drainage; most breast lymphatics flow here.

- Internal mammary lymph nodes: Deep, along the sternum; important secondary pathway.

- Lymphatic mapping and biopsy: Clinical procedures (such as sentinel lymph node biopsy) rely on this anatomy for cancer staging and treatment decision-making.

Most lymphatic drainage heads toward the axilla (underarm), but variations can occur. Understanding lymphatic routes is essential for breast cancer surgery and prevention of lymphedema after treatment.

Blood Supply

The breasts are richly supplied with blood. Major arteries include:

- Internal mammary (thoracic) artery: Supplies the inner parts of the breast.

- Lateral thoracic artery: Feeds the outer breast and axillary tail.

- Intercostal arteries: Small branches that nourish the deeper tissues.

Venous drainage mirrors arterial supply, with blood flowing primarily to the axillary and internal thoracic veins.

Nerve Supply

Breast sensation is regulated by branches of the intercostal nerves (T3–T5 levels), with the nipple sensory supply specifically from the fourth intercostal nerve. Nerves control muscle fibers in the nipple and transmit sensory signals critical during breastfeeding and for sexual sensation.

Development and Changes Throughout Life

The human breast is dynamic, changing considerably during various stages of life:

- Infancy and Childhood: Breast tissues are rudimentary in both sexes.

- Puberty: Under the influence of hormones, female breasts enlarge with development of glandular tissue and fat deposition. Males do not develop functional lobules.

- Pregnancy: Marked proliferation of ducts and lobules prepares the breast for lactation; increased blood flow and sensitivity are common.

- Lactation: Full maturation of alveoli and ducts; milk production and secretion occur actively.

- Menopause: Glandular elements shrink; fat content may increase, leading to overall changes in size and consistency.

The Male Breast

Male and female breasts share the same basic structures: skin, ducts, connective tissue, and adipose tissue. However, males typically lack the lobule and alveolar development necessary for milk production. Male breast tissue can still develop certain conditions, including gynecomastia (benign enlargement) and, uncommonly, breast cancer.

Common Breast Changes and Concerns

Being familiar with normal breast anatomy can make it easier to detect potential problems. Some changes are harmless, while others warrant medical attention:

- Lumps and Nodules: May be benign cysts or fibroadenomas but require professional evaluation.

- Changes in Skin Texture: Dimpling or puckering may signal underlying issues.

- Nipple Discharge: Can result from benign or malignant causes; unusual color or persistent output should prompt assessment.

- Pain: Often hormonal, but persistent or localized pain deserves evaluation.

- Swelling or Redness: May be signs of infection or inflammatory conditions.

Breast Health and Self-Care

Maintaining breast health relies on regular self-exams, awareness of family history, and timely screening. Key points for proactive care:

- Become familiar with your own normal breast anatomy and how changes occur throughout the menstrual cycle or with age.

- Report any persistent changes—lumps, nipple changes, skin dimpling, or unusual pain—to a healthcare provider.

- Undergo screening mammography as recommended, particularly for women over 40 or those with increased risk factors.

- Understand that most breast changes are benign but should be investigated if persistent or unusual.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the main function of the breast?

A: The primary function is to produce and deliver milk to nourish an infant, thanks to a complex network of lobules and ducts.

Q: Why is breast anatomy important in health and disease?

A: Understanding the structure aids in recognizing abnormal changes, detecting diseases like breast cancer early, and guiding effective treatment, especially since most cancers arise from glandular elements such as the terminal ductal lobular unit.

Q: Why do breasts sag with age?

A: Over time, the supportive Cooper’s ligaments stretch and the proportion of glandular to fatty tissue declines, leading to natural drooping (ptosis).

Q: Are lymph nodes and lymphatic drainage important for breast health?

A: Yes, most breast lymph drains to the axillary (underarm) nodes. This is critical for immune surveillance and has major implications in the spread and treatment of breast cancer.

Q: Do men have breasts, and can they get breast cancer?

A: Yes, men have similar breast tissue (except for specialized lobules). While rare, men can develop breast cancer and other breast health issues.

References

- Johns Hopkins Medicine, “Anatomy of the Breasts.”

- UCLA Health, Breast Imaging Teaching Resources.

- Johns Hopkins Pathology, Overview of the Breast.

- PMC, The Lymphatic Anatomy of the Breast and its Implications.

References

Read full bio of Sneha Tete