Anatomy of a Joint: Structure, Types, and Health Insights

Explore the fascinating structure of joints, how they function, types, and ways to keep them healthy for lifelong mobility.

Anatomy of a Joint

Joints are one of the most essential anatomical features of the human body. They are the connections between bones that ensure mobility, stability, and structural support. Understanding joint anatomy helps illuminate how our bodies move, how we can protect our joints from injury or disease, and why joint pain and dysfunction can impact quality of life. This article provides an in-depth exploration of joint structure, the components that give joints their function and flexibility, different joint types, common joint problems, and practical guidance for lifelong joint health.

What Is a Joint?

A joint (also called an articulation) is the point where two or more bones meet in the body. Joints allow for movement, provide mechanical support, and help maintain the body’s structure. They can range from immovable connections—such as those in the skull—to highly mobile arrangements such as the shoulder and hip.

- Function: Facilitate body movement (walking, running, grasping, bending, etc.).

- Support: Help maintain posture and bear weight.

- Protection: Absorb and distribute forces to prevent injury to bones and vital organs.

The Basic Structure of a Joint

Though joints vary greatly in complexity and mobility, most contain a similar set of anatomical components. The major parts of a typical movable (synovial) joint include:

- Cartilage: A smooth, flexible tissue that covers the ends of bones in a joint, reducing friction and acting as a cushion.

- Synovial Membrane: This thin lining covers the inner surface of the joint capsule and produces synovial fluid, which lubricates the joint.

- Ligaments: Strong bands of fibrous tissue that connect bone to bone, providing stability and limiting excessive movement.

- Tendons: Tough cords of connective tissue connecting muscles to bones, facilitating movement when muscles contract.

- Bursa: Small, fluid-filled sacs that sit between bones, tendons, and muscles to decrease friction and cushion pressure points.

- Joint Capsule: A tough, flexible sleeve that surrounds the joint, containing the synovial membrane and helping stabilize the joint.

- Meniscus or Articular Disk: Pads of cartilage present in some joints (eg. knee), providing additional cushioning and support.

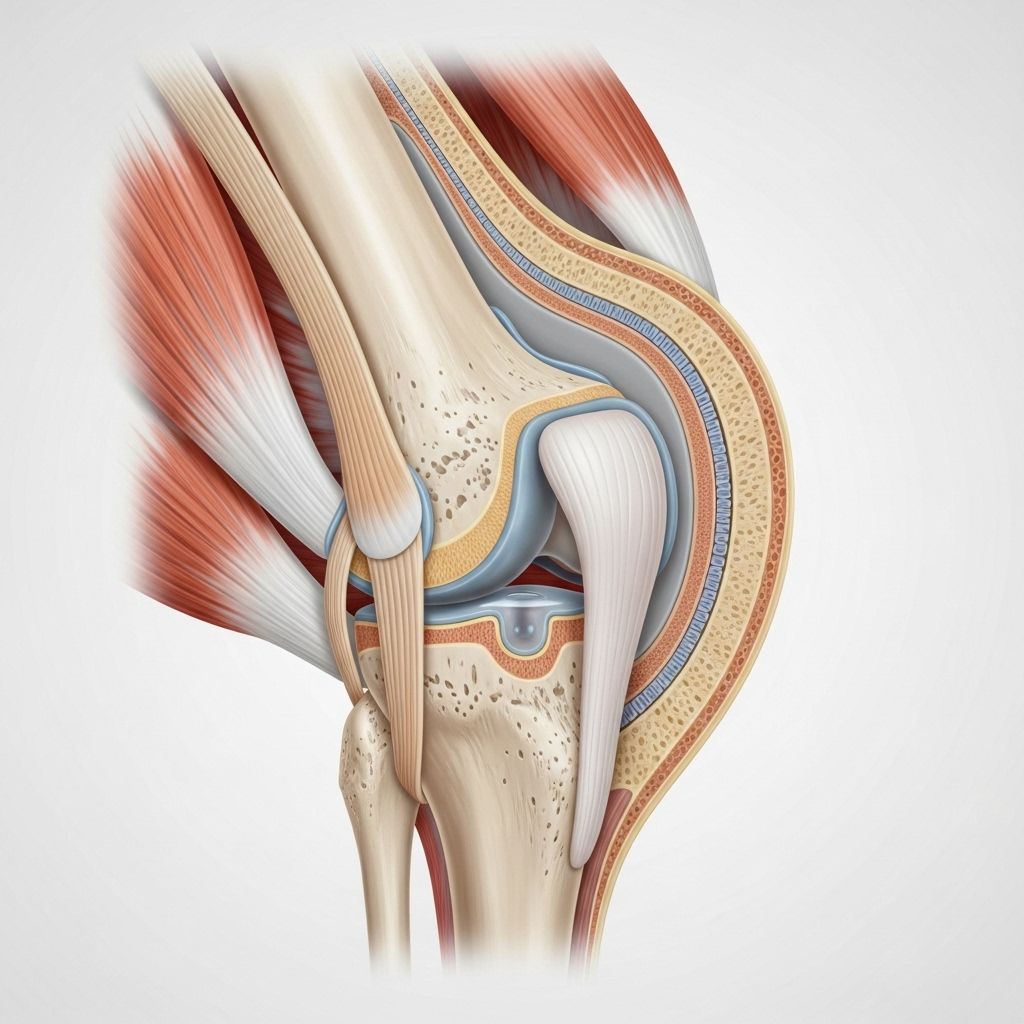

An Illustrated Overview

To visualize, imagine the knee: The ends of the femur and tibia are capped with smooth cartilage, enveloped by a synovial membrane and enclosed in a strong capsule. Ligaments stabilize the joint, the menisci add shock absorption, and nearby bursae minimize friction where tendons or skin move across bones.

Main Components of Joints

1. Articular Cartilage

This specialized, smooth and resilient connective tissue covers the surfaces of bones at movable joints. Its functions include providing a smooth, lubricated surface for low-friction articulation and absorbing shock. Cartilage contains chondrocytes cells within a matrix of collagen fibers and proteoglycans, but it has no blood vessels or nerves—making cartilage slow to heal when injured.

2. Synovial Membrane and Synovial Fluid

The synovial membrane lines the inner surface of the joint capsule, producing synovial fluid. This straw-colored liquid lubricates the joint, nourishes cartilage, and removes waste products, essential for smooth, pain-free movement.

3. Ligaments

Ligaments are strong, flexible bands of connective tissue. Unlike tendons (which attach muscle to bone), ligaments connect bones to other bones. They stabilize joints, control range of motion, and prevent dislocation.

4. Tendons

The tendons are connective tissues made mostly of collagen. They transmit the force of muscle contraction to bones, allowing for joint movement. Despite being strong, tendons are less elastic than muscles or ligaments, making them more susceptible to certain types of injury (such as tendonitis).

5. Bursa

Bursae are small, fluid-filled sacs embedded in tissues around joints. Their main role is to minimize friction and cushion movement where muscles, tendons, or skin rub against bone or each other.

6. Meniscus (in some joints)

The meniscus is a crescent-shaped wedge of cartilage, found in certain joints (notably, the knee and jaw). It acts as a shock absorber, provides structural stability, and aids in even distribution of joint pressure.

Types of Joints in the Human Body

Joints can be classified in several ways: by the tissue that connects them (structural classification), or by range of movement (functional classification).

| Joint Type | Structural Class | Mobility | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrous | Fibrous connective tissue | Immovable (synarthrotic) | Sutures in the skull, teeth in jaw |

| Cartilaginous | Cartilage | Slightly movable (amphiarthrotic) | Vertebral discs, pubic symphysis |

| Synovial | Synovial cavity, capsule | Freely movable (diarthrotic) | Shoulder, knee, finger joints |

Structural Classification of Joints

- Fibrous Joints: Bones are joined by fibrous connective tissue. These joints allow little or no movement. Examples include cranial sutures and the attachment between tooth and jawbone (gomphosis).

- Cartilaginous Joints: Bones are united by cartilage (either hyaline or fibrocartilage). They allow limited movement, such as the cartilage connecting vertebrae (intervertebral discs), or the pubic symphysis.

- Synovial Joints: The most common and most mobile type. Bones are separated by a synovial cavity, lined by membrane, and stabilized by a joint capsule, ligaments, and muscles.

Functional Classification of Joints

- Synarthrosis: Immovable joint (e.g., skull sutures).

- Amphiarthrosis: Slightly movable joint (e.g., vertebral discs).

- Diarthrosis: Freely movable joint (e.g., knee, elbow).

Types of Synovial Joints and Their Movements

Synovial joints are highly specialized for movement, and come in several distinct shapes, each permitting a different range and type of motion:

- Hinge Joint: Allows motion in one plane, like a door hinge. Examples: elbow, knee, ankle.

- Ball and Socket Joint: Rounded bone head fits into a cup shaped socket, allowing movement in all directions, including rotation. Examples: shoulder, hip.

- Pivot Joint: Permits rotational movement around a single axis. Example: radius and ulna bones of the forearm at the elbow, the first and second vertebrae in the neck.

- Condyloid (Ellipsoid) Joint: Permits motion in two planes (flexion/extension, abduction/adduction). Example: wrist joint, finger joints.

- Saddle Joint: Both bones have a concave and a convex portion, fitting together like a rider on a saddle. Provides movement in two planes. Example: base of the thumb (carpometacarpal joint).

- Gliding (Plane) Joint: Flat bones glide against each other, permitting sliding or translational motion. Example: joints between wrist or ankle bones (carpals, tarsals).

Nerves and Blood Supply to Joints

Joints require a healthy supply of nerves and blood for function, sensory feedback, and healing. Key details include:

- Nerve Supply: Joints are innervated by sensory nerves that detect pain and position (proprioception). The Hilton law states that nerves supplying the muscles moving a joint also supply the joint itself.

- Blood Supply: Small blood vessels branch around joints, nourishing the capsule, synovial membrane, and adjacent tissues. Some parts, like cartilage, have no direct blood supply and rely on diffusion from surrounding tissues.

Muscles and Joint Stability

Muscles crossing a joint produce movement, but they also provide dynamic stability. Strong muscles and tendons help stabilize joints, protect against injury, and maintain proper alignment. Muscular weakness or imbalance can increase the risk of dislocation, strain, or degenerative changes.

Common Problems That Affect Joints

Joints are subject to various disorders due to injury, wear-and-tear, inflammation, or genetic conditions. Frequent joint issues include:

- Osteoarthritis: Degenerative joint disease characterized by cartilage breakdown, pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility.

- Rheumatoid Arthritis: Autoimmune inflammation damaging joint linings, causing swelling, pain, deformity, and functional loss.

- Injuries: Sprains (ligament tears), strains (muscle/tendon injuries), dislocations, and fractures.

- Bursitis and Tendonitis: Inflammation of bursae or tendons, often from repetitive motion.

- Infections: Septic arthritis occurs when bacteria enter the joint, causing swelling and severe pain.

Keeping Your Joints Healthy

Protecting joints and supporting lifelong health requires a combination of healthy lifestyle practices and awareness. Consider these strategies:

- Exercise Regularly: Weight-bearing and strengthening exercises support muscles and bones, help maintain joint mobility, and reduce arthritis risk.

- Maintain Healthy Weight: Reduces extra stress on weight-bearing joints like knees and hips.

- Practice Good Posture: Reduces abnormal stress on joints, especially the back, neck, and knees.

- Protect from Injury: Use proper techniques when lifting, playing sports, or exercising. Wear supportive gear as needed.

- Listen to Your Body: Rest when you feel pain or discomfort. Early treatment is key for joint injuries.

- Stay Flexible: Incorporate stretching or yoga to maintain joint range of motion.

- Stay Hydrated and Eat Well: A balanced diet with adequate vitamins (especially vitamin D and calcium) supports joint health.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How many joints does the human body have?

The human body contains over 300 joints, with more than half found in the hands and feet. The exact number depends on which types of joints and connections are included.

What are the most common types of joints?

Synovial joints are the most common type, characterized by high mobility and a fluid-filled capsule. Examples include the knee, shoulder, and finger joints.

Why do joints sometimes crack or pop?

Cracking or popping sounds (crepitus) often result from gas bubbles in the synovial fluid collapsing, tendons snapping over bone, or minor movement between joint surfaces. This is generally harmless unless accompanied by pain or swelling.

What causes joint pain?

Joint pain may be due to injury (sprains, strains, fractures), arthritis, inflammation, excessive use, or infection. Persistent pain should be evaluated by a healthcare professional.

How can I strengthen my joints?

Strengthening muscles around the joint with resistance exercises, staying active, and maintaining flexibility through stretching helps support and protect joints.

Key Takeaways for Lifelong Joint Health

- Joints are vital points connecting bones, providing mobility and support.

- Healthy joints depend on the synergy of cartilage, ligaments, tendons, muscles, and flexibility.

- A proactive lifestyle—including regular exercise, weight management, balanced nutrition, and prompt injury care—promotes optimal joint function as you age.

- Consult a healthcare provider if you experience joint pain, stiffness, or swelling that interferes with normal activities.

References

Read full bio of Sneha Tete