The Starfish Wasting Epidemic: Unraveling the Collapse of West Coast Sea Stars

A decade-long ecological crisis is dissolving sea stars and reshaping Pacific coastal ecosystems—scientists are finally closing in on answers.

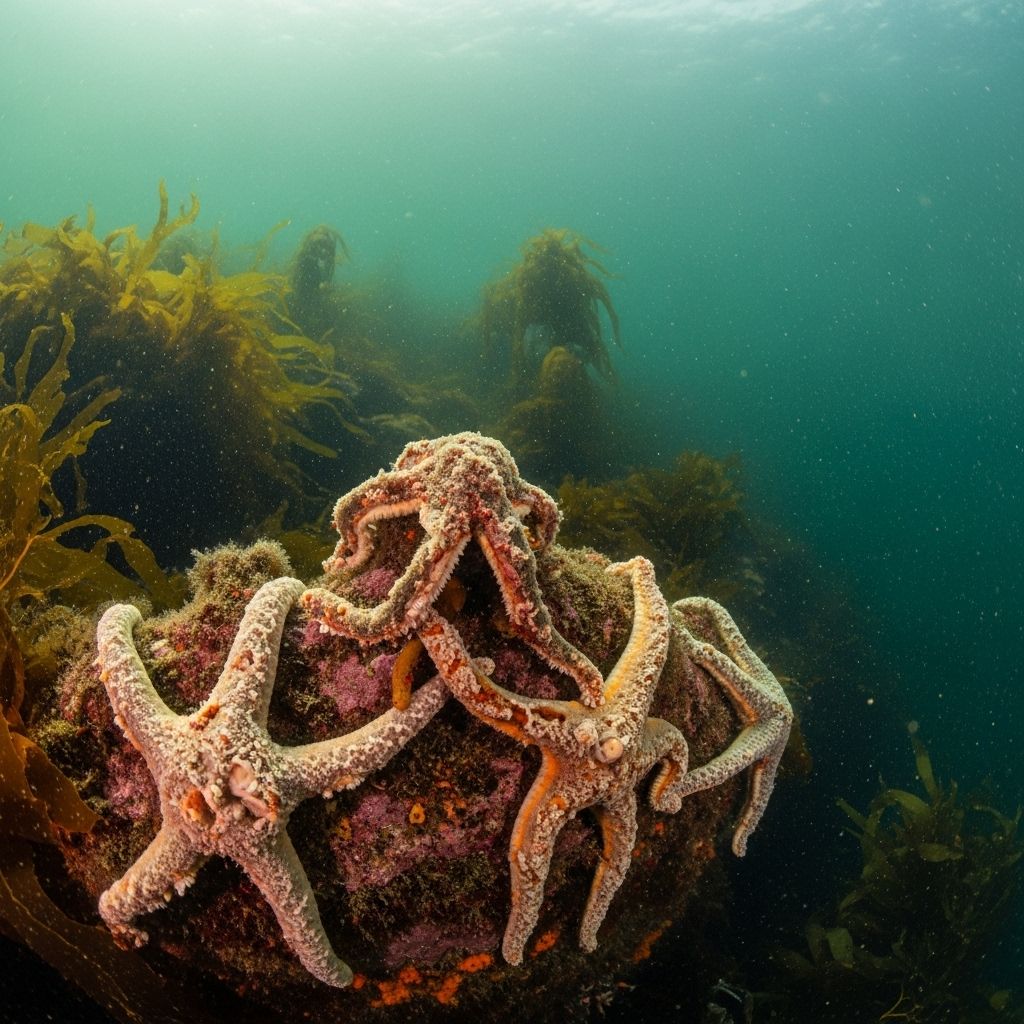

A devastating mystery has been unfolding beneath the waves of the Pacific Ocean for over a decade. Sea stars, also known as starfish, once keystone members of rocky coastal ecosystems, have been dying in the millions along the US and Canadian West Coast. Striking not just in scope but in the sheer horror of its symptoms, this affliction—known as sea star wasting disease (SSWD)—has left researchers, conservationists, and coastal communities alarmed and searching for answers. Recent scientific breakthroughs are illuminating both the culprit and the catastrophic consequences for entire marine environments.

What Is Sea Star Wasting Disease?

Beginning in 2013, scientists and volunteers from Alaska to Southern California started noticing a dramatic decline in sea star populations. The die-off hit more than 20 species, but none more so than the sunflower sea star (Pycnopodia helianthoides)—arguably the largest sea star species in the world, with specimens often spanning up to a meter in diameter and brandishing over 20 arms. The wasting disease causes sea stars to lose their limbs, their tissues melt, and ultimately, their bodies dissolve into a grotesque, gelatinous sludge within days or weeks.

- Symptoms include:

- White lesions on the surface

- Limb curling, twisting, and contortion

- Autotomy (self-amputation) of arms

- Rapid tissue decay and softening

- Dissolution into a ‘gooey’ mass, sometimes leaving only skeletal ossicles

Early detection of these symptoms was already a cause for concern, but the ensuing scale and rapidity of the die-off shocked marine scientists and ecologists. Gone were countless ochre, sunflower, and other star species once visible on rocky tidal shores and underwater kelp forests. By some estimates, over 90% of sunflower sea stars vanished within years.

Tracking the Outbreak: Scale and Impact

This epidemic, described as one of the most destructive marine diseases ever witnessed, spanned from Alaska through California. The 2013–2014 event was the most severe—affecting a wide range of species and reaching unprecedented geographic breadth. Although sea star die-offs had occurred regionally in past decades, the current outbreak was unmatched in both intensity and scope.

Some of the most severely impacted species included:

- Sunflower star (Pycnopodia helianthoides): >90% population reduction

- Ochre star (Pisaster ochraceus): Noted as a ‘keystone species’ due to its pivotal ecological role

- Rainbow, giant pink, giant, mottled, leather, vermilion, sun, six-armed, and bat stars: All experienced varying degrees of population loss

Of the estimated 5 billion sunflower stars affected globally, virtually none remain in many locales, like the continental US, landing the species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of threatened species.

The Mystery: What Causes Sea Star Wasting Disease?

For years, the cause of SSWD eluded scientists. Early hypotheses centered on a viral culprit, but repeated studies failed to consistently identify a singular virus associated with all outbreaks.

By contrast, evidence now points to a bacterial pathogen—specifically, a strain of Vibrio pectenicida—as the primary driver behind the disease. The breakthrough came in the summer of 2025, when a coalition of researchers from the Hakai Institute, University of Washington, and other partners isolated and confirmed this strain as causative:

- Vibrio pectenicida:

- A genus of bacteria with several species known to cause disease in marine animals (and, in rare cases, humans)

- Associated with multi-species die-offs in corals, shellfish, and now, sea stars

- Lab exposure to isolated V. pectenicida reliably induced wasting symptoms mirroring wild outbreaks

- Presence confirmed in tissue samples dating back to previous years’ outbreaks

This bacterial discovery is a landmark moment for marine disease ecology, closing a key knowledge gap and directing future research and conservation response.

Why Did It Take So Long to Find the Cause?

There were several reasons the search for the culprit lasted over a decade:

- The disease presents a constellation of symptoms and affects more than 20 species, some more quickly or visibly than others.

- Initial suspicions of a viral agent clouded scientific focus; viral metagenomics provided ambiguous results.

- Complexities in culturing, isolating, and testing marine pathogens delayed experimental confirmation.

Which Species Are Affected?

While sunflower stars garnered the most attention due to their size and ecological significance, a wide spectrum of West Coast sea stars have been afflicted. Documented species with observed wasting include (but are not limited to):

- Pycnopodia helianthoides – sunflower star

- Pisaster ochraceus – ochre star

- Orthasterias koehleri – rainbow star

- Pisaster brevispinus – giant pink star

- Pisaster giganteus – giant star

- Evasterias troschelii – mottled star

- Solaster – sun star

- Dermasterias imbricata – leather star

- Mediaster aequalis – vermilion star

- Leptasterias – six-armed stars

- Patiria miniata – bat star

The progression and visibility of symptoms varies among species and even among individuals at the same site.

Keystone Loss: Broader Ecosystem Impacts

Sea stars, especially the ochre and sunflower species, are regarded by ecologists as ‘keystone predators’—organisms that hold disproportionate influence over the community composition of their habitats. The consequences of their removal are profound and multi-layered:

| Role of Sea Stars | Effect of Their Decline |

|---|---|

| Predate on sea urchins & mussels | Urchin populations surge, devouring kelp forests and reducing biodiversity |

| Maintain rocky intertidal balance | Altered competition among barnacles, snails, and limpets; shifts in community structure |

| Enhance habitat complexity | Loss of sea stars simplifies benthic habitat, leading to decreased marine diversity |

| Support kelp forest health | Kelp loss undermines shelter and food for countless marine fish and invertebrates |

One of the most visible aftermaths has been the rapid proliferation of sea urchins, formerly kept in check by sunflower stars. Swarming unchecked, these urchins overgraze kelp, converting lush underwater forests into so-called ‘urchin barrens’ where little else survives. Such fundamental changes threaten fisheries, carbon sequestration, and shoreline stability.

Current Status and Ongoing Threats

While the worst of the mass die-off occurred in 2013–2014, flare-ups of SSWD continue, varying seasonally and regionally. Some locations see only sporadic cases now, while others witness recurring population crashes. Recovery has been slow or absent for the most vulnerable species.

- Monitored locations continue to show depressed population levels.

- Ongoing outbreaks threaten any nascent recovery efforts.

- Potential interaction with climate stress, such as warmer waters, may exacerbate infection risk and mortality rates.

Conservationists have expressed alarm that this decline may be irreversible for certain species without human intervention or dramatic environmental changes.

Ecological and Conservation Lessons

The SSWD crisis is a warning about unseen vulnerabilities in marine ecosystems and the latent power of microbial pathogens.

- Long-term ecological monitoring proved essential to documenting, analyzing, and eventually solving the mystery.

- Community science (citizen science) groups played a role in reporting symptomatic animals and wider patterns of die-off.

- Early hypotheses, sometimes misleading, underscore the importance of experimental validation in ecology.

- SSWD’s impact exemplifies how losing a keystone predator ripples through an ecosystem, altering everything from species competition to carbon storage.

How Are Scientists Monitoring Progress?

Researchers track populations of affected star species using long-term survey sites, photographic records, and sample collection. Biodiversity surveys help measure indirect effects on other intertidal and kelp forest inhabitants. New tools such as population graphing, interactive mapping, and advanced genetic screens are now integral to capturing slow recovery or renewed outbreaks.

Recovery: A Slow, Uncertain Road?

Most experts agree that natural recovery will be slow, especially for the sunflower star. Protective measures, marine protected areas, and, potentially, future re-introduction efforts may become necessary to hasten population rebound.

- Long lifespans and slow reproductive rates constrain recovery even when individual animals survive disease exposure.

- Secondary threats such as ocean warming, acidification, and altered predator-prey dynamics complicate the outlook.

- Recent identification of the primary pathogen may eventually lead to mitigation, but there is no direct treatment for wild populations at this time.

The loss underscores the urgent need for conservation vigilance in marine systems—and the perils of relying on one or a few species to maintain ecological equilibrium.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is sea star wasting disease (SSWD)?

A: SSWD is a fast-acting marine disease affecting more than 20 species of sea stars. It causes lesions, tissue decay, limb loss, and often leads to total body dissolution (‘melting into goo’), devastating populations along the Pacific coast.

Q: What causes sea star wasting disease?

A: A recently discovered strain of the bacterium Vibrio pectenicida has been identified as the main cause. The bacteria infect sea star tissues, triggering the cascade of wasting symptoms observed in affected regions.

Q: Are any starfish species safe from this disease?

A: Over 20 species have shown symptoms, but some, like the sunflower star and ochre star, have suffered the most significant declines. Other species may be partially or temporarily unaffected, but almost all are at risk if the disease persists.

Q: How does the disease impact ocean ecosystems?

A: The loss of keystone sea stars, especially sunflower and ochre stars, leads to surges in prey species like sea urchins and mussels, which in turn devastate kelp forests and diminish habitat complexity, resulting in widespread loss of marine biodiversity.

Q: Can people help restore sea star populations?

A: Monitoring programs and marine protected areas contribute to conservation, while research continues into the biology and possible resistance of surviving sea stars. Direct human intervention (such as captive breeding/release) remains a prospect for the most imperiled species but is not yet widely applied.

Conclusion: The Starfish Wasting Crisis—A Call to Action

The West Coast’s starfish crisis reveals how swiftly a disease can upend whole ecosystems, and how scientific persistence—bolstered by public engagement—can eventually illuminate even the murkiest marine mysteries. Now the challenge is to turn that understanding into action, safeguarding the fragile interconnected web of ocean life for future generations.

References

- https://www.opb.org/article/2025/08/08/sea-star-wasting-disease-discovery/

- https://marine.ucsc.edu/research/sea-star-wasting/

- https://www.washington.edu/news/2025/08/04/researchers-have-found-the-culprit-behind-sea-star-wasting-disease/

- https://www.opb.org/article/2025/08/05/northwest-scientists-crack-case-melting-sea-stars-after-decade/

- https://www.usgs.gov/centers/western-fisheries-research-center/news/solving-mystery-sea-star-wasting-disease-a

- https://www.statesmanjournal.com/story/tech/science/environment/2025/08/04/sea-star-wasting-disease-study-pacific-coast/85515931007/

Read full bio of medha deb