The Resurrection of Extinct Animals: Science, Ethics, and Ecological Implications

Exploring the challenges, breakthroughs, and controversies in the quest to revive extinct species and reshape our planet

The Fascination With Extinct Animal Resurrection

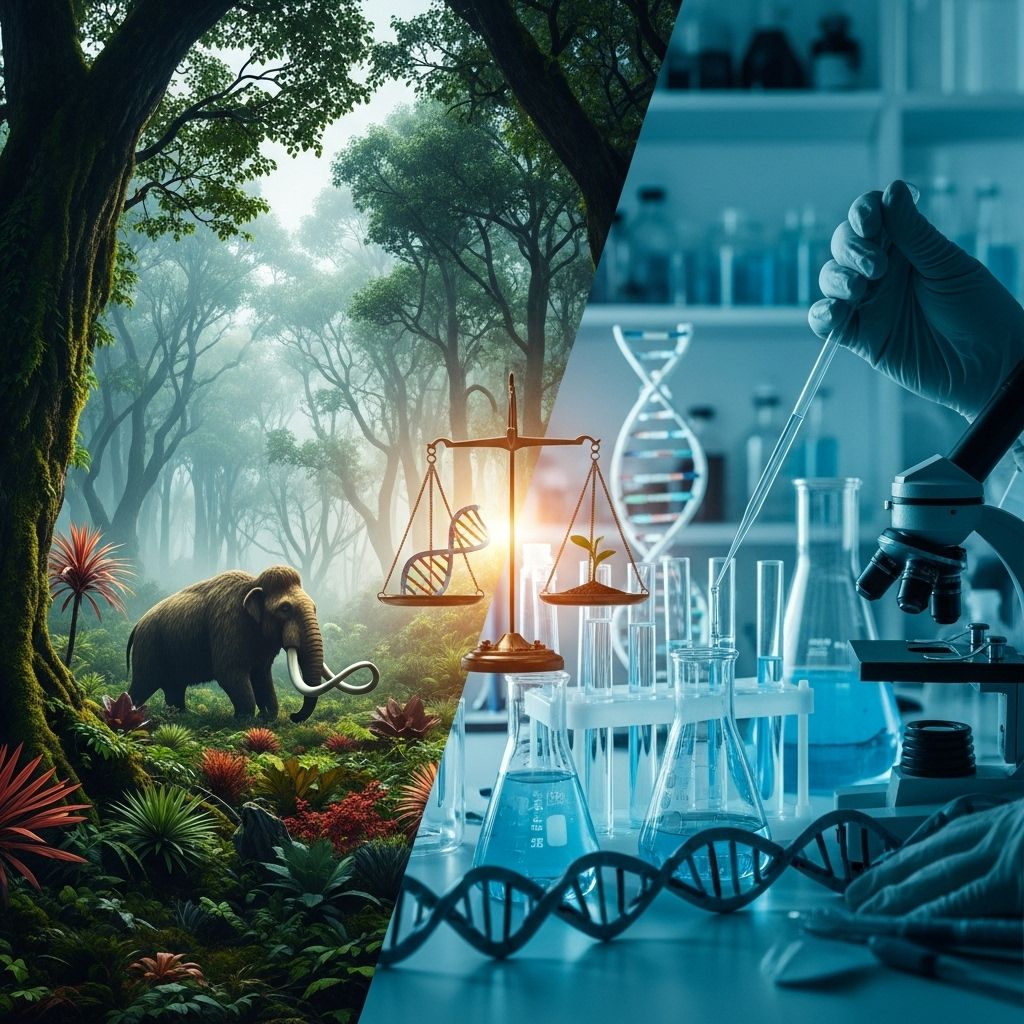

Human fascination with lost species dates back centuries, but modern science is now investigating methods to bring extinct animals back to life. The quest, often termed de-extinction, blends genetics, cloning, ecology, and profound ethical considerations. While these efforts promise exciting breakthroughs, they also raise challenging questions about human responsibility towards nature and the consequences of tampering with the past.

What Is De-Extinction?

De-extinction (also called resurrection biology) refers to using biotechnology to recreate organisms that resemble extinct species or restore their unique traits. This can involve cloning, genome editing, or selective breeding. Scientists hope that advancing de-extinction could help conserve biodiversity, restore lost ecological functions, and even rectify previous human-caused extinctions.

- Cloning: Replicating the genome of extinct animals in living surrogate species.

- Genome Editing: Editing DNA in close relatives to mimic extinct traits using tools like CRISPR.

- Selective Breeding: Encouraging reproduction of living animals displaying traits reminiscent of extinct relatives.

The Historical Context: Species Lost and Lessons Learned

The rate of species extinction has accelerated due to human impact, including habitat destruction, overhunting, and climate change. Famous examples of lost species inspiring de-extinction efforts include:

- Passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) – once astonishingly abundant, wiped out in the early 20th century.

- Quagga (Equus quagga quagga) – an African zebra subspecies, extinct since the late 19th century, now a target for selective breeding.

- Woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) – vanished thousands of years ago, studied for cold-adapted gene revival.

- Aurochs (Bos primigenius) – Eurasian wild cattle, extinct since 1627, subject of genome editing and breeding projects.

Each extinction event offers tragic reminders of lost biodiversity, but also motivates re-evaluation of conservation strategies.

How Can Extinct Animals Be Resurrected?

The science of de-extinction has advanced rapidly. There are several main approaches:

- Ancient DNA Extraction: Recover DNA from preserved remains, fossils, or museum specimens.

- Genetic Reconstruction: Fill in gaps or modify the DNA of a close living relative to match the extinct species.

- Cloning and Surrogacy: Implant reconstructed embryos into surrogate mothers of related species.

- Selective Back-Breeding: Breed living relatives to concentrate extant genes that resemble the extinct form.

Each step poses enormous technological, biological, and ethical challenges—but also opportunities to address conservation in new ways.

Examples of De-Extinction Efforts

Passenger Pigeon Revival

The passenger pigeon, once numbering in the billions, disappeared due to commercial hunting and habitat loss. De-extinction attempts focus on:

- Museum DNA analysis: Decoding the genetic differences between extinct passenger pigeons and their closest living relatives, the band-tailed pigeon.

- Genome editing: Modifying band-tailed pigeons to re-create passenger pigeon traits. These edited birds are bred in captivity, with release into the wild targeted for the coming decades, although technical roadblocks have delayed the schedule.

- Ecological studies: Researching how forest ecosystems might respond to a reintroduction of these birds, which once influenced tree distribution and forest structure.

The Woolly Mammoth Project

The idea of resurrecting the woolly mammoth has captured global imagination. Preserved mammoth remains from Siberian permafrost provide ancient DNA, but the DNA is typically too fragmented for simple cloning. Some approaches under exploration:

- Mammoth genes in Asian elephants: Using genome editing to insert cold-adapted mammoth genes into elephants. The aim is to engineer hybrid animals capable of surviving harsh Arctic environments.

- Environmental restoration: Scientists speculate that rewilded mammoths could help restore tundra ecosystems, reverse permafrost thaw, and combat climate change.

Quagga Selective Breeding Program

The Quagga Project in South Africa aims to bring back the extinct quagga through selective breeding of plains zebras that show quagga-like traits.

- DNA studies have confirmed that the quagga is a subspecies of the plains zebra, raising hopes for restoration via selective breeding.

- Special breeding camps have produced foals increasingly similar in appearance to historical quaggas, known as “Rau quaggas”—though not genetically identical to their extinct ancestors.

Aurochs Genome Editing and Breeding

The extinct aurochs—a wild ancestor of modern cattle—has inspired projects using genome editing and breeding with domestic cattle to revive its traits.

- Some European teams focus on reconstructing aurochs-like cattle by identifying and selecting for their physical and genetic traits within existing cattle breeds.

Neanderthals: Humanity’s Extinct Cousins

Surprisingly, Neanderthals have also been considered for de-extinction—though this prospect sparks heated ethical and philosophical debate. Scientists possess high-quality Neanderthal DNA but face major hurdles regarding surrogate mothers, genetic completeness, and moral concerns.

Pet Cloning: Extending the Concept to Domestic Animals

Animal resurrection isn’t limited to wild species. Pet cloning is a booming industry, with families seeking to bring back beloved pets through biotechnology. While not technically de-extinction, pet cloning involves complex emotional and ethical considerations, particularly around animal welfare and the meaning of identity.

- Examples include cloning dogs and cats for grieving owners, sparking debate about the distinction between memories and genetic legacy.

- Some veterinarians question whether cloned pets offer true solace, as each animal’s personality is shaped both by genes and life experiences.

Ethical and Ecological Challenges

The dream of bringing back extinct animals is fraught with significant risks and responsibilities. Experts highlight concerns such as:

- Animal welfare: Cloning requires surrogates and often leads to health problems for animals involved.

- Ecological impacts: Reintroducing extinct species could disrupt existing ecosystems or create invasive populations.

- Genetic authenticity: Revived species, being hybrids or edited descendants, may not truly replicate extinct populations.

- Conservation priorities: Diverting resources to de-extinction could deprive current conservation efforts.

- Ethical debates: From the value of correcting past human mistakes to the moral costs of ‘playing God,’ experts and the public alike are divided.

Potential Benefits and Hopes for the Future

Despite daunting challenges, proponents of de-extinction cite several promising benefits:

- Restoring lost ecological functions: Revived species could fill ecological niches left empty after their extinction.

- Learning from genetic diversity: Research into ancient DNA may help protect living relatives from disease or environmental change.

- Reversing human harm: De-extinction may demonstrate a commitment to rectifying damage caused by past actions.

- Public engagement: High-profile de-extinction efforts can inspire public interest and funding for conservation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is de-extinction?

A: De-extinction is the process of reviving extinct species using techniques like cloning, genome editing, or selective breeding to create new individuals that closely resemble those that have disappeared.

Q: Which animals are scientists currently trying to bring back?

A: Notable candidates include the passenger pigeon, woolly mammoth, quagga, aurochs, and—interestingly—Neanderthals.

Q: What are the main ethical concerns surrounding de-extinction?

A: Concerns include animal welfare, ecological risk, authenticity of revived species, and the broader question of whether humans should intervene in nature in this way.

Q: Could resurrected species survive in today’s environment?

A: Scientists study habitat viability and ecological dynamics carefully. For long-extinct species, their original ecosystems may have changed so drastically that survival or ecological balance cannot be guaranteed.

Q: Does de-extinction distract from conserving endangered species?

A: Critics argue that focusing on spectacular de-extinction projects may divert funding and attention from urgent conservation needs, whereas advocates suggest it could enhance broader conservation efforts.

Major Extinct Animal Candidates for Resurrection

| Species | Extinction Date | Main Revival Method | Ecological Role | Effort Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passenger Pigeon | 1914 | DNA Editing / Cloning | Seed dispersal, forest ecology | Active research, goal: 2029-2032 captive breeding |

| Quagga | 1883 | Selective Breeding | Grazing, savanna habitats | Ongoing, several “Rau quaggas” bred |

| Woolly Mammoth | ~4,000 years ago | Genome Editing | Tundra grazing, climate moderation | Active, technical barriers remain |

| Aurochs | 1627 | Back-Breeding / Editing | Cattle ancestor, grassland maintenance | Various ongoing projects |

| Neanderthal | ~28,000 years ago | Cloning (proposed) | Human relative; unknown impact | Theoretical; severe ethical issues |

Scientific, Social, and Moral Implications

While the resurrection of extinct animals excites scientists and the public, its consequences reverberate through science, philosophy, and conservation policy:

- Scientific curiosity: Unlocks deeper understanding of genetics, adaptation, and ancient ecosystems.

- Social debate: Sparks discussions over our role as planetary stewards and the ethics of reversing extinction.

- Moral dilemmas: Raises questions about animal suffering, ecological disruption, and the value of authenticity in nature.

Conclusion: The Path Ahead for Resurrection Biology

The journey to resurrect extinct animals is filled with scientific breakthroughs and ethical quandaries. As researchers continue to unravel ancient DNA and engineer new forms of life, society must balance hope for restored biodiversity with caution over unforeseen impacts. Whether or not the dreams of reviving lost species are fully realized, de-extinction is reshaping our understanding of evolution, conservation, and humanity’s place in the natural world.

Related Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Are resurrected species truly the same as their extinct predecessors?

A: Genetically, revived species may not be 100% identical due to incomplete DNA, reliance on living relatives, and gaps in knowledge. Their traits may be similar but subtle differences remain.

Q: What is the timeline for bringing back species like the passenger pigeon or woolly mammoth?

A: Estimates vary widely due to technological hurdles. For passenger pigeons, captive breeding may begin by 2029-2032; woolly mammoth projects face longer timelines with “as soon as 2027” cited optimistically but not yet feasible.

Q: Could de-extinction efforts help with fighting climate change?

A: Some scientists claim that mammoth rewilding could help restore Arctic grasslands and stabilize permafrost, potentially mitigating climate change, though this is still unproven and requires more research.

References

Read full bio of medha deb