Noise Pollution Maps: A Jarring Journey Through an Overstimulated World

Explore the unsettling reality of environmental noise pollution with global noise maps, their health impacts, and what can be done to restore quieter spaces.

Few environmental hazards are as invisible and yet as deeply pervasive as noise pollution. In our modern world, the constant hum, roar, and clatter of urban life form an unrelenting backdrop that affects billions of people, countless wildlife species, and the very health of our cities. But while air and water pollution are mapped and measured with painstaking detail, noise pollution has only recently begun to receive similar attention. Thanks to evolving technologies and a growing field of environmental acoustics, noise maps now provide a haunting visual representation of the sounds that saturate our environment—and the few places where silence remains sacred.

Mapping the Invisible: The Purpose and Power of Noise Maps

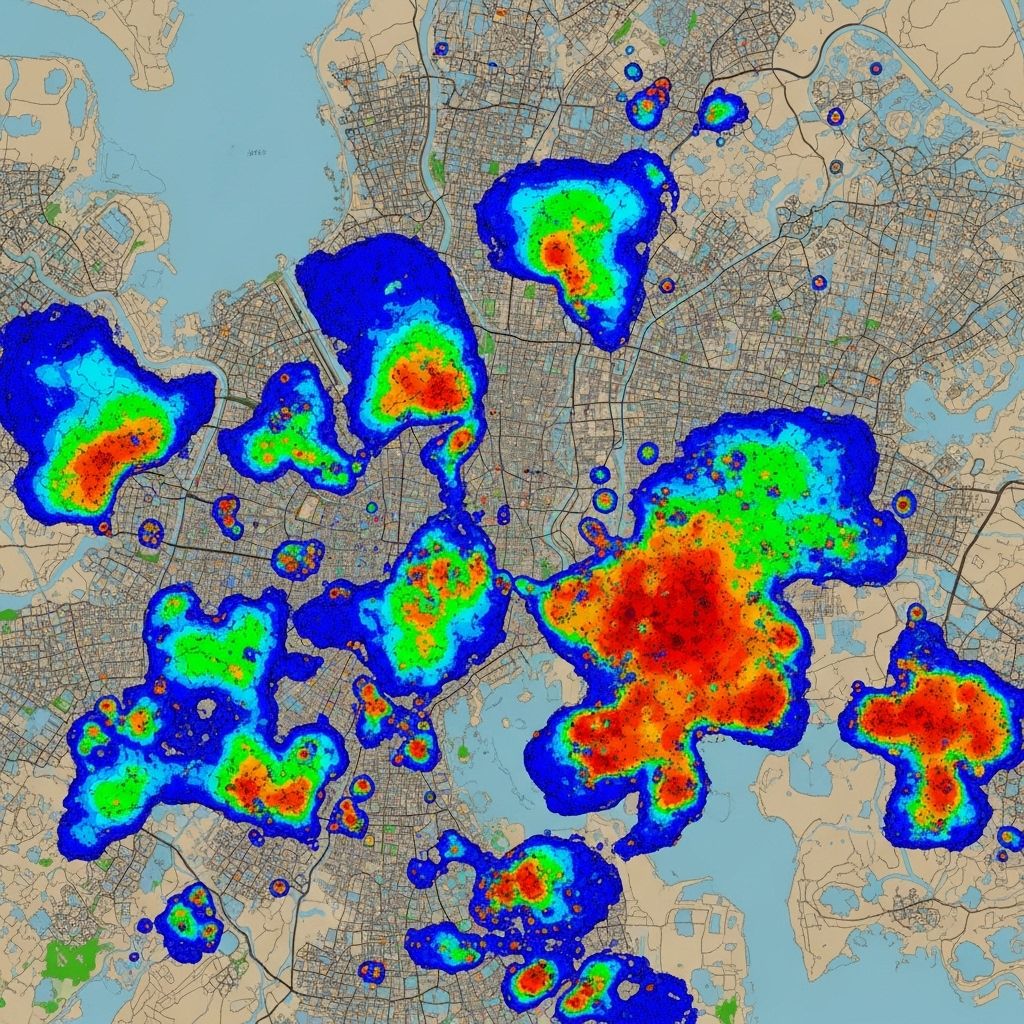

Unlike pollutants you can see or smell, environmental noise is intangible and often underestimated. Enter noise pollution maps: graphical representations that layer real-world data—traffic patterns, flight paths, urban density, natural landscapes—over geographic regions to reveal the true extent of our sonic environment.

- Technological foundations: Modern noise maps draw from a range of data, including traffic counts, industrial activity, and even meteorological information. Software platforms, often based on Geographic Information Systems (GIS), aggregate these inputs to predict and visualize spatial patterns in sound exposure.

- Data accuracy and modeling: Tools such as kriging and co-kriging—advanced statistical interpolation methods—improve the precision of these noise maps. By weighting noise measurements from multiple points, these techniques help generate a more realistic picture of average (and peak) noise levels across cities or regions.

- Public health advocacy: These maps are now used by urban planners, public health officials, and environmental advocates to inform zoning, guide traffic improvements, and identify communities at heightened risk from chronic noise exposure.

The result is a vivid tapestry: jagged red lines for highways, pockets of deep purple in city centers, and rare washes of blue in rural and protected natural areas. The images are as alarming as they are instructive.

What Is Noise Pollution, Really?

Not all sound is harmful; natural soundscapes are essential for human well-being and crucial to many ecological processes. Noise pollution refers specifically to unwanted, disruptive, or harmful sound—typically created by human activity—that interferes with normal life or environmental quality. The most common sources include:

- Transportation: Automobiles, trucks, trains, airplanes, and even maritime shipping lanes.

- Industrial operations: Factories, construction sites, and power plants.

- Urban activity: Nightlife, public events, and dense residential noisescapes.

The difference between benign background noise and disruptive pollution lies in both intensity (measured in decibels, dB) and the time of day, context, and population sensitivities involved. Chronic exposure to elevated noise levels, above 55 dB in daytime and 40 dB at night per World Health Organization guidelines, is associated with a range of adverse health effects.

Where the Noise Never Stops: A Glimpse at Global Maps

The most dramatic results from contemporary noise maps can be found in major urban centers across Europe, Asia, and North America. The European Environment Agency’s noise maps, for instance, reveal vast tracts of densely populated urban areas colored above 60 dB, often stretching unbroken for miles. Highways, railways, and airports create corridors of acoustic overload that cut through cities day and night.

| Location | Dominant Noise Sources | Peak Decibel Levels | Population Exposed (approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| London, UK | Road traffic, rail, aviation | Up to 70 dB | Over 8 million |

| New York City, USA | Road traffic, construction | 65-75 dB | Over 4 million (exceeding 65dB) |

| Paris, France | Road, rail, neighborhood activities | 65-70 dB | Over 3 million |

| Mumbai, India | Road, nightlife, industry | 60-75 dB | Millions (exact exposures unknown) |

By contrast, the world’s quietest places—if they still exist—are typically found in remote mountainous regions, protected forests, or specially designated wilderness zones. Here, baseline sound levels can drop below 20 dB, described by scientists as approaching ‘the threshold of hearing.’

The Human Cost of a Noisy World

1. Physical and Mental Health

Emerging research has firmly established that chronic noise exposure doesn’t just fray nerves—it can:

- Increase risk of cardiovascular disease (including heart attacks and hypertension)

- Heighten stress, anxiety, and symptoms of depression

- Disrupt sleep patterns, often leading to insomnia and reduced cognitive performance

- Contribute to hearing loss—much earlier in life than previously recognized

- Impair children’s learning and memory retention

Worst of all, noise pollution rarely affects society equally—it disproportionately harms children, elderly people, and those living in poverty near loud infrastructure. Night shift workers, for instance, face persistent sleep disturbances due to traffic and neighborhood noise when they try to rest during the day.

2. Social Fragmentation and Inequity

Noisy environments can undermine social cohesion and neighborhood harmony. In communities where excessive noise is chronic and unavoidable, researchers often see elevated rates of:

- Social withdrawal and reduced community engagement

- Higher levels of conflict and disputes between neighbors

- Feelings of helplessness and loss of agency

Wildlife Under Threat: A Sonic Hazard to Ecosystems

The consequences of environmental noise ripple far beyond the human community. Many wildlife species, from birds and frogs to whales, depend on the natural soundscape for communication, navigation, and survival. As noise levels rise, scientists have observed profound impacts:

- Altered animal behavior: Birds in cities often sing at night, or at much higher pitches, just to be heard above the urban din. This can interfere with mating and territory establishment.

- Impaired reproduction: Some female frogs exposed to traffic noise fail to recognize or find suitable mates, threatening entire populations.

- Predation and foraging: Mammals and bats reduce foraging activity in noisy zones, as their ability to detect prey by sound is compromised.

- Population decline: When combined with other stressors, like food scarcity or disease, chronic noise can reduce animal health and survival—potentially leading to local extinctions.

Even protected natural areas and parks are not immune. Thanks to roadways, tourism, and air travel, noise levels in many national parks now exceed those of nearby cities.

The Challenge of Measuring Noise: Methods and Limitations

Mapping a variable as fleeting and context-dependent as noise is far from simple. Scientists rely on several approaches:

- Field measurements: Placing sensitive microphones across representative areas, often for weeks or months at a time, to collect real-world decibel data.

- Predictive modeling: Using statistical methods—such as kriging and co-kriging—to estimate noise levels in unsampled locations, improving map accuracy.

- GIS integration: Combining noise data with spatial information (road networks, land use, wind conditions) to track how sound propagates through cities, forests, and open spaces.

Yet, there are challenges:

- Mapping at different times of day yields dramatically different patterns—rush hour versus midnight, weekday versus weekend.

- Weather, topography, and even local flora can dampen or amplify sound.

- Most global noise maps are still modeled, not directly measured—meaning they carry inherent uncertainties.

Nonetheless, the growing sophistication of these models is narrowing the gap between perception and reality.

Pushing Back: Efforts to Reduce Environmental Noise

As awareness of noise pollution grows, so too does the push to mitigate its sources:

- Urban planning innovations: Zoning laws, noise barriers, strategic plantings, and the design of quieter roads and rail lines.

- Technology upgrades: Quieter aviation engines, electric public transport, and ‘green’ building techniques that insulate against external noise.

- Policy interventions: Curfews for loud activities, restrictions on night flights, and public health campaigns.

- Protection of quiet spaces: Identifying and preserving natural silence ‘hotspots’ in parks and wilderness areas for future generations.

Some European cities have pioneered ‘quiet zones’ where traffic is restricted and natural soundscapes restored. Meanwhile, public pressure continues to mount for stricter noise regulations—especially in neighborhoods chronically exposed to industrial or transportation noise.

Why Silence Matters: Psychological and Spiritual Dimensions

The battle against noise pollution is not merely about decibels—it’s about restoring depth and variety to our sensory environment. Silence, or even the presence of nondestructive natural sounds (like water or birdsong), is increasingly recognized as vital for:

- Stress reduction and mental clarity

- Restorative sleep and cognitive performance

- Opportunities for reflection, meditation, and connection to nature

- Cultural and spiritual practices that depend on tranquility

According to a growing body of evidence, exposure to natural soundscapes—streams, wind through trees, animal calls—supports physical and emotional healing. But in a world filled with mechanical clamor, such experiences are becoming alarmingly rare.

Global Perspectives: Contrasts and Commonalities

While noise pollution is a global concern, exposures and attitudes vary dramatically between regions:

- Europe: Rigorous noise mapping and actionable benchmarks across the EU; many cities enforce strict maximum noise limits and regularly update noise maps to reflect urban change.

- United States: Regulations typically focus on occupational (workplace) noise and environmental noise in specific settings (e.g., near airports or highways), but broader mapping is still gaining ground.

- Asia: Mega-cities like Mumbai and Beijing experience intense noise pollution, with rural ‘sound havens’ quickly shrinking.

- Global South: Rapid urbanization often outpaces enforcement, with sprawling informal settlements bearing the brunt of unregulated industrial and traffic noise.

Looking Forward: A Call for Action

Noise pollution may be invisible, but it is not insurmountable. As noise maps become more precise, the disparities they reveal can guide targeted action—from technological innovation to policy reform and community engagement. Building a quieter world means:

- Empowering citizens with real-time data so they can demand change and protect their health.

- Incentivizing industry and city planners to prioritize soundscapes as part of green infrastructure.

- Investing in studies that track the complex interplay between sound, health, and equity at both local and global scales.

- Championing quiet as a common good, worth defending in every community.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a noise map is worth a thousand arguments: an urgent, graphic case for a world where silence is not a luxury, but a right.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the main sources of noise pollution?

A: The dominant sources are transportation (vehicles, aircraft, trains), industrial operations, construction, nightlife, and densely populated urban areas.

Q: How do noise pollution maps work?

A: They combine measured and modeled data with GIS software to estimate and visually represent average sound levels across wide geographic areas, helping identify noise hotspots and quiet zones.

Q: What health effects are linked to chronic noise exposure?

A: Research associates long-term noise exposure with elevated cardiovascular risk, stress, sleep disorders, hearing impairment, and cognitive deficits, particularly in vulnerable groups.

Q: How is wildlife affected by environmental noise?

A: Many species experience disrupted communication, reduced mating success, altered foraging, and population declines—especially in areas near roads, airports, and cities.

Q: Can cities or individuals do anything to reduce noise pollution?

A: Yes. Cities can enforce stricter regulations, redesign infrastructure, and preserve quiet spaces. Individuals can use soundproofing, support advocacy efforts, and choose quieter transport or lifestyles where possible.

References

Read full bio of Sneha Tete