Keystone XL Pipeline: Timeline, Controversy, and Legacy

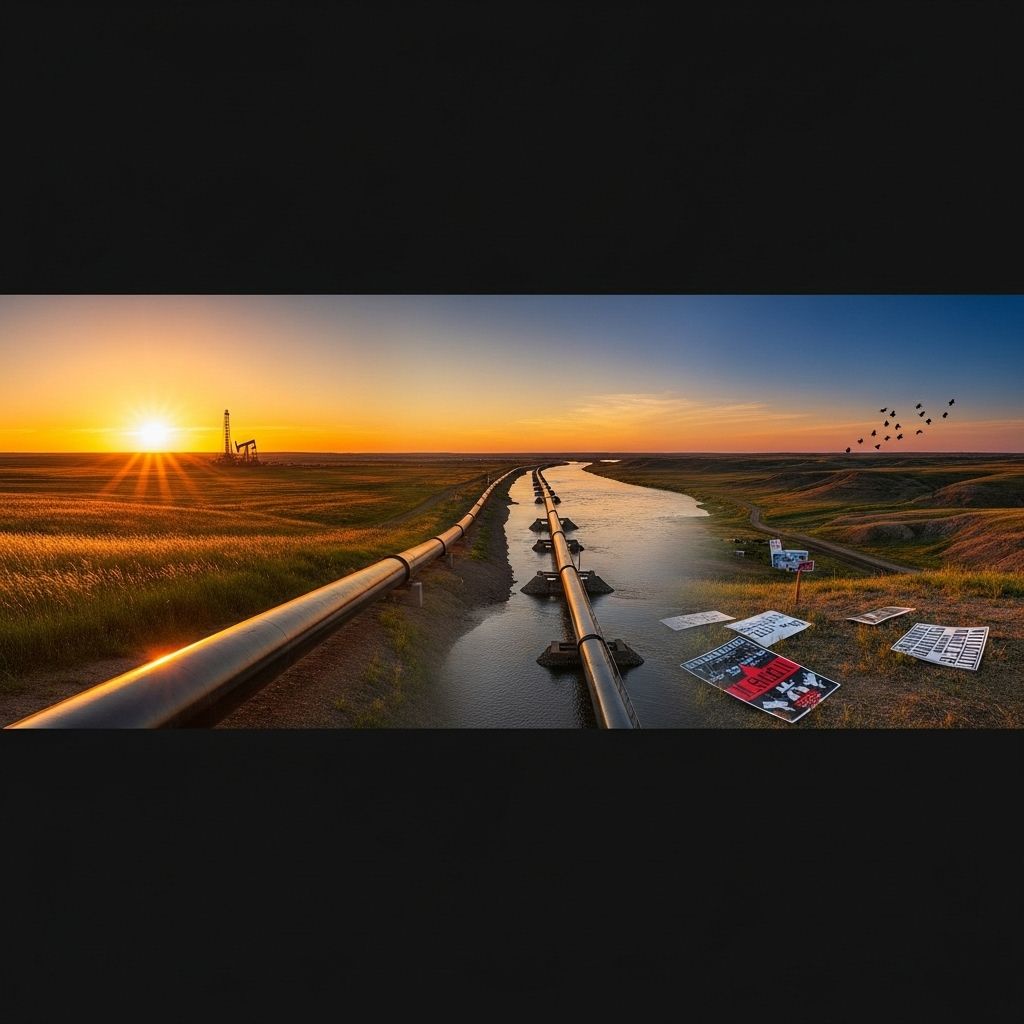

Tracing the rise, debates, and ultimate cancellation of the Keystone XL Pipeline and its impact on energy and climate policy.

The Keystone XL Pipeline stands as a pivotal controversy in North American energy development. Spanning nearly two decades, its saga showcases complex intersections of energy policy, environmental activism, Indigenous rights, and climate change strategy. This article provides a detailed timeline, examines the long-running debates, explores the environmental and social impacts, and assesses the enduring legacy of one of the continent’s most contested infrastructure projects.

What Is the Keystone XL Pipeline?

The Keystone XL Pipeline was designed as a major expansion of the pre-existing Keystone Pipeline system, intended to transport crude oil extracted from Alberta’s oil sands in Canada to refiners and terminals in the United States including Steele City, Nebraska, Cushing, Oklahoma, and Houston, Texas.

The primary aim was to create a more direct, higher-capacity route traversing Montana, South Dakota, and Nebraska, thus delivering up to 830,000 barrels of oil per day over an approximately 1,200-mile stretch.

While the original Keystone phases were completed and became operational between 2010 and 2014, the XL phase became a flashpoint for environment, climate, legal, and Indigenous resistance, and was eventually cancelled.

Timeline of Key Events

- 2005 62008: Inception and Early Proposals

- 2005: The project was proposed by TransCanada Corporation (now TC Energy).

- 2007: Canadian approval received to convert sections of existing natural gas pipeline to carry crude oil.

The Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada objects, citing concerns about national energy security and job creation. - 2008: U.S. State Department issues a Presidential Permit enabling cross-border construction. The Keystone XL extension is formally proposed.

- 2010 62014: Construction of Keystone Pipeline Phases

- 2010: Phase I completed, running oil from Hardisty, Alberta, to Steele City, Nebraska, and onward to Wood River Refinery (Illinois) and Patoka Terminal.

- 2011: Phase II connects Steele City, Nebraska, through Kansas to Cushing, Oklahoma.

- 2014: Gulf Coast Project extends pipeline from Cushing to Gulf refineries in Texas.

- 2008 62021: The Keystone XL Saga

- 2008: Keystone XL expansion proposal faces widespread environmental and Tribal opposition upon announcement.

- 2010: Draft environmental reviews highlight concerns about spills and climate impact.

- 2015: President Barack Obama rejects the pipeline after significant activism and review delays.

- 2017: President Donald Trump issues an executive order to revive Keystone XL.

- 2019: Trump issues a new Presidential Permit for construction. Legal battles erupts over environmental reviews and Indigenous rights.

- 2020: TC Energy begins construction in northern Montana following approvals for rights-of-way.

- 2021: President Joe Biden revokes Presidential Permit as part of climate policy; TC Energy halts the project.

Understanding the Pipeline System: Phases and Route

- Phase 1: 3,456 km (2,147 mi) from Hardisty, Alberta to Wood River Refinery (Illinois) and Patoka Tank Farm. Canadian section involved conversion of gas pipeline and new construction.

- Phase 2: 468 km (291 mi) from Steele City, Nebraska south through Kansas to Cushing, Oklahoma (U.S. oil hub).

- Phase 3 (Gulf Coast Project): Extended from Cushing, Oklahoma to refineries near Houston, Texas.

- Phase 4 (Keystone XL): Proposed a new, large-diameter line from Hardisty, Alberta directly to Steele City through Montana and South Dakota, bypassing the longer original route. Not built.

| Phase | Route | Status | Length | Capacity | Operational Since |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Hardisty, AB 6 Illinois (Wood River, Patoka) | Operational | 2,147 mi (3,456 km) | ~590,000 bpd | 2010 |

| Phase 2 | Steele City, NE 6 Cushing, OK | Operational | 291 mi (468 km) | ~510,000 bpd | 2011 |

| Phase 3 | Cushing, OK 6 Houston, TX (Gulf Coast) | Operational | 485 mi (780 km) | ~700,000 bpd | 2014 |

| Phase 4 (XL) | Hardisty, AB 6 Steele City, NE (Direct) | Cancelled | ~1,200 mi (1,930 km) | 830,000 bpd (planned) | N/A |

The Heart of the Debate: Supporters vs. Opponents

- Supporters claimed the pipeline would:

- Create jobs — up to 20,000 direct and indirect jobs during peak construction.

- Increase North American energy security.

- Support economic development in Canada and the U.S.

- Lower oil transport costs and reduce reliance on foreign imports.

- Opponents focused on:

- Risks of oil spills and leaks contaminating land and water supplies.

- Long-term climate impact from increased extraction and burning of oil sands crude.

- Environmental damage to sensitive ecosystems along route, including Sandhills region in Nebraska.

- Infringement of Indigenous lands and lack of consultation and consent.

- Lack of permanent employment benefits for local communities versus environmental risks.

Environmental and Social Impact

From inception, the pipeline attracted intense scrutiny over its environmental footprint. Several key issues defined opposition:

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Oil sands extraction produces 17% more GHGs per barrel than conventional oil, contributing to global warming.

- Oil Spill Incidents: Over 22 leak events between 2010 and 2020, including a major spill in Kansas in 2022 of 14,000 barrels, raising questions about pipeline safety and preparedness.

- Water Resource Threats: Pipeline traverses critical aquifers and river systems (Ogallala Aquifer, Sandhills), raising alarm over contamination risks.

- Wildlife and Ecosystem Disruption: Fragmentation of prairies, wetlands, and migration routes for endangered species.

- Impacts on Indigenous Communities: Many Tribal Nations opposed the project over treaty rights and risks to cultural sites and drinking water.

Political Shifts and Legal Battles

- Obama Administration: Delayed and ultimately blocked approval over environmental and climate policy concerns.

- Trump Administration: Fast-tracked permits, arguing economic benefit and energy independence, but faced fierce legal challenges and state-level opposition.

- Biden Administration: Revoked the permit as a climate action, halting ongoing construction and signaling a move away from fossil fuel infrastructure.

Milestones, Setbacks, and Cancellation

- 2007 62008: Permits, acquisition of stakeholder approval, industry backing.

- 2010 62014: Construction and operation of initial Keystone Pipeline phases; environmental critiques escalate.

- 2015: Obama denies Presidential Permit for XL phase.

- 2017 62020: Trump administration reapproves, sparking a new round of legal and social conflict; some early XL construction begins.

- 2021: Biden rescinds permit on first day in office; TC Energy cancels the project in June.

Spills, Safety Records, and Technical Performance

- Leak Incidents: At least 22 reported incidents between 2010 and 2020; most notably:

- May 2011: Multiple leaks prompt corrective safety actions from U.S. authorities.

- 2017: 9,700 barrels leaked in South Dakota.

- 2022: Major Kansas spill led to closure and repair.

- Throughput: Despite design capacity of 830,000 barrels/day, average actual throughput between 2012 62022 was 550,000 6650,000 barrels/day.

Legacy and Lessons Learned

- The Keystone XL Pipeline remains a landmark case in environmental policy, legal activism, and energy transition.

- It foregrounded debates about climate action versus energy development and positioned environmental justice and Indigenous rights at the center of infrastructure planning.

- Its cancellation signals the growing weight of climate-focused decision-making in North American energy policy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What was the main objective of the Keystone XL Pipeline?

A: The pipeline’s goal was to deliver large volumes of crude oil from Alberta’s oil sands directly to refining and storage hubs in the U.S., increasing capacity and reducing transportation costs.

Q: Why did the Keystone XL Pipeline become so controversial?

A: It became a flashpoint over environmental protection, climate change, Indigenous rights, land use, and balancing fossil fuel dependency with sustainability goals.

Q: Was any part of the Keystone XL Pipeline built?

A: Although construction began on some sections in Montana (2020), the XL extension was never completed. Earlier phases of the broader Keystone Pipeline system remain operational.

Q: What were the environmental risks cited?

A: Main risks included oil spills, ecosystem disruption, water contamination, and elevated greenhouse gas emissions from oil sands extraction and processing.

Q: What does the cancellation of Keystone XL mean for future energy projects?

A: It sets precedent for climate accountability in infrastructure approval, highlighting that political, legal, and social opposition can override industry ambitions.

Conclusion

The story of the Keystone XL Pipeline reflects evolving priorities in energy strategy, environmental stewardship, and community advocacy. Its lengthy legal and political journey underscores the necessity for balanced infrastructure planning — weighing economic opportunity against environmental risk and social impact. As the transition toward lower-carbon energy continues, the Keystone XL case offers enduring lessons on public engagement, regulatory process, and the power of activism in shaping energy futures.

References

Read full bio of Sneha Tete