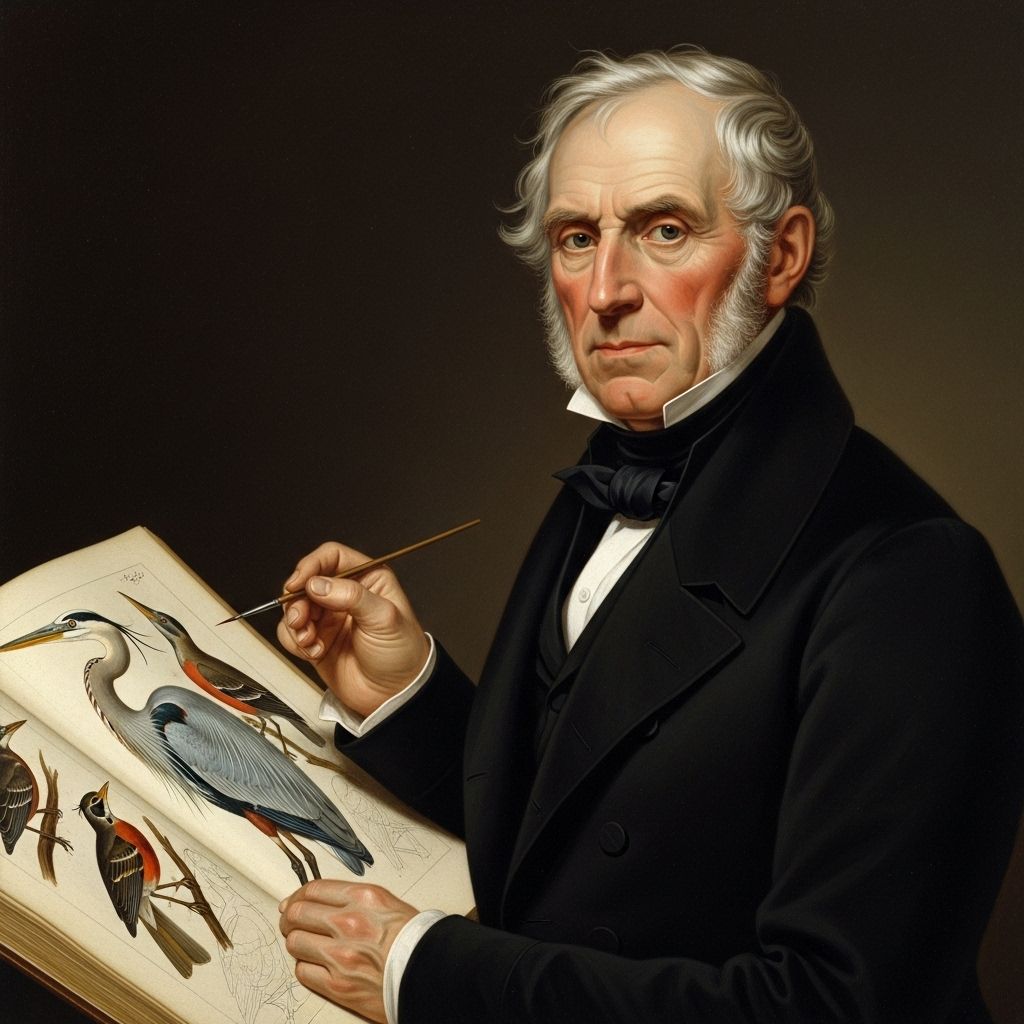

Surprising Facts About John James Audubon: The Artist Behind America’s Birds

Discover the hidden stories, controversies, and achievements that shaped John James Audubon's legacy as one of America's most influential naturalists.

John James Audubon is often remembered as an unmatched artist and naturalist whose monumental work, The Birds of America, continues to shape our understanding of wildlife. His life, however, abounds with contradictions, mysteries, and innovations, some charming and others contentious. This article explores the lesser-known aspects of Audubon’s legacy, revealing a far more nuanced portrait of the man behind the magnificent paintings.

His Background Was Shrouded in Mystery

The details of John James Audubon’s birthplace and early years were purposefully obscured throughout his life. Born on April 26, 1785, in Les Cayes, Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti), Audubon was the illegitimate son of a French sea captain and a Creole servant. His mother died when he was still an infant, and he was later brought to France, where he was adopted by his father’s wife. Raised in Nantes, France, he was given the name Jean-Jacques Fougère Audubon. The family’s fortunes and Audubon’s background were complicated by the disruptions of the Haitian Revolution and family secrets about his origins, resulting in lifelong ambiguity that Audubon himself did not fully dispel, sometimes altering details of his story to fit social expectations of the period.

Sent to America to Escape Conscription

At the age of 18, Audubon was sent to America, partly to escape conscription into Napoleon’s army. Arriving in 1803, he settled at the family’s Mill Grove estate in Pennsylvania. Tasked with overseeing lead mining operations, he soon found himself more attracted to the natural world around him than to business, spending his time exploring the countryside, observing, and sketching birds .

The First Bird Bander in America

One of Audubon’s most interesting contributions to science was his early experimentation with bird banding. In 1804, fascinated by the return of Eastern Phoebes every spring, he carefully tied threads around the legs of nestlings to see if they would return to the same location the following year. This predates organized bird banding by about a century and is recognized as America’s first documented bird banding experiment .

A Businessman Who Faced Ruin and Prison

- After marrying Lucy Bakewell in 1808, Audubon moved to Kentucky and tried his luck at running a general store.

- His business ventures were mixed at best; economic downturns and debt led him to bankruptcy and brief imprisonment in 1819.

- These hardships, however, refocused his attention on his true passion—nature and art.

His Art Was Self-Taught and Highly Innovative

Although Audubon had some childhood lessons in art and music, he was largely self-taught as a naturalist and illustrator. He strove to surpass the static scientific illustrations of his contemporaries, seeking to depict birds in lifelike, dynamic poses within their natural environments. His methods, though sometimes controversial (he often shot the birds he painted to study them up close), resulted in revolutionary and emotionally compelling images. His life-sized paintings set a new standard for ornithological illustration.

He Funded His Work Through Sheer Persistence—and Sacrifice

- After repeated rejections by American publishers, Audubon sailed to England in 1826, bringing his collection to European art patrons.

- His dramatic style suited the Romantic tastes of the era, and he found success, securing financial support and a publisher for his masterpieces.

- Audubon often lived in poverty, relying on his wife’s income as a teacher and selling painted portraits, lessons, and commissioned artwork to survive.

The Birds of America: A Monumental Achievement

Audubon’s most celebrated work, The Birds of America, was published in four volumes between 1827 and 1838. Produced in the “double-elephant folio” format, each volume measured about 39 by 26 inches. It contained 435 hand-colored engravings of North American birds at actual size, many of which had never been described scientifically before. The ambitions and scope of this work, along with its artistic merit, make it one of the greatest achievements in natural history publishing.

Controversy Surrounds His Collecting Methods and Legacy

Audubon’s methods have generated debate among modern conservationists and historians. To achieve anatomical accuracy, he routinely killed the birds he intended to paint. Although common practice at the time, today’s ornithologists and wildlife advocates take a more critical view. Audubon also hunted prolifically and sometimes exaggerated his own exploits in his field journals. Additionally, he was involved in the slave trade, both as an owner and a trader, a fact that continues to shape how institutions and the public grapple with his legacy.

He Was Not the Only Pioneer—But He Outshone His Peers

While famed for his comprehensive cataloguing of American birds, Audubon was not the first to attempt such a project. Alexander Wilson, a Scottish-American poet and ornithologist, published his own multivolume American Ornithology earlier. However, Audubon’s combination of scientific rigor and artistic beauty eventually eclipsed Wilson’s work, setting him apart both in the U.S. and in Europe.

Beyond Birds: Contributions to Mammalogy

Though celebrated for avifauna, Audubon also published a significant work on North American mammals, The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, in collaboration with the Reverend John Bachman and his sons, after completing The Birds of America. This ambitious series further displayed his dedication to documenting the continent’s natural world in both image and text.

His Wife, Lucy Bakewell Audubon, Was Key to His Success

Throughout his life, Audubon relied on the unwavering support of his wife, Lucy. She managed family affairs, supported the family as a governess and teacher during his absence, and championed his artistic career, even when success seemed unlikely. Without Lucy’s encouragement and labor, Audubon’s achievements might never have come to fruition.

Later Life and Death

Audubon remained prolific in his later years, working on supplemental editions and other natural history projects. He died on January 27, 1851, in New York City, leaving behind a complex personal legacy but an indelible mark on natural science and art. His final resting place is in Trinity Cemetery, Manhattan.

Audubon Societies and a Mixed Legacy

Audubon’s impact on bird conservation is immense, with the formation of the Audubon Society and similar organizations helping to inspire wildlife protection and environmental awareness. Yet, over time, his views, treatment of enslaved individuals, and environmental methods have provoked ongoing debate. Many contemporary naturalists and organizations now seek to reconcile his artistic contributions with critical examination of his personal actions and beliefs.

At a Glance: Key Facts About John James Audubon

| Fact | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | John James Audubon (born Jean-Jacques Fougère Audubon) |

| Born | April 26, 1785, Saint Domingue (now Haiti) |

| Died | January 27, 1851, New York City |

| Profession | Ornithologist, Naturalist, Painter |

| Famous Works | The Birds of America, The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America |

| Lasting Legacy | Artistic innovation, wildlife documentation, namesake of Audubon Society |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Was John James Audubon formally trained as an artist?

A: Audubon had some early lessons, but his distinctive artistic style was primarily self-taught, refined through devotion and field observation.

Q: Did Audubon really kill birds to paint them?

A: Yes, Audubon typically killed the birds he depicted, a method considered normal in his era but viewed differently today.

Q: What made The Birds of America so revolutionary?

A: The work depicted birds in life-sized, dynamic poses against natural backdrops, combining scientific documentation with dramatic composition, unlike the static images typical of earlier naturalists.

Q: Did Audubon’s background as the child of a slave owner affect his legacy?

A: Audubon’s connections to slavery—as an owner and trader—are now widely acknowledged and discussed, complicating public perceptions of his legacy and prompting reassessment by institutions bearing his name.

Q: What is the Audubon Society?

A: Founded in the late 19th century, the Audubon Society is dedicated to the protection of birds and their habitats. Although the organization honors Audubon’s contributions, it continues to reflect on and address his full legacy.

Conclusion: A Life as Complex as His Art

John James Audubon’s drive and artistry helped elevate both ornithology and wildlife painting. His personal journey—from uncertain beginnings and financial setbacks to creative triumph—embodies the exuberance, contradictions, and challenges of his era. Audubon’s work captures not just the diversity of American birdlife but also the complicated human story behind scientific discovery and artistic genius.

References

- https://www.audubongalleries.com/education/audubon.php

- https://www.audubon.org/content/john-james-audubon

- https://www.biography.com/scientists/john-james-audubon

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-James-Audubon

- https://guides.lib.lsu.edu/c.php?g=1133247&p=8270717

- https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/583260/john-james-audubon-facts

- https://johnjames.audubon.org/john-james-audubon-0

- https://nycbirdalliance.org/audubon-name/john-james-audubon

Read full bio of Sneha Tete