How Trees Sense, Respect, and Support Their Neighbors

Discover how trees communicate, make room for each other, and form cooperative forest communities benefiting the entire ecosystem.

Trees have long captivated human imagination, but only in recent decades have scientists uncovered just how dynamic, social, and interconnected these silent giants can be. Far from standing as isolated individuals, healthy trees are now understood as active participants in a community—one characterized by subtle communication, cooperation, and even neighborly restraint. In forests around the world, emerging research is revealing profound intelligence in how trees grow, compete, and, perhaps most surprisingly, give each other space to thrive.

The Awareness of Trees: Beyond Simple Organisms

Trees cannot walk, talk, or move in the way animals do, but this does not mean they lack awareness. Instead, they possess highly evolved sensing and signaling mechanisms that allow them to gather information about their environment—including the presence, size, and health of neighboring trees.

- Light detection: Trees use photoreceptors in their leaves and branches to detect both the intensity and direction of sunlight, allowing them to sense if a neighbor is casting shade.

- Tactile feedback: As branches grow outward, they can bump into the leaves or stems of neighbors. This contact leads to responsive growth patterns that help avoid direct competition or damage.

- Chemical signaling: Trees can pick up cues from volatile organic compounds released by nearby plants, warning of stress, pests, or changes in conditions.

These forms of perception equip trees with much more precise awareness of their surroundings than previously assumed.

Trees Give Room: Evidence of Cooperative Growth

Perhaps the most compelling indicator of tree awareness is the phenomenon where trees actively avoid crowding one another, producing the distinctive visual pattern known as crown shyness. Instead of interlacing their uppermost branches, the crowns of adjacent trees often form graceful, puzzle-like gaps—a behavior that has fascinated observers for generations.

This phenomenon is especially apparent in forests of certain species, such as eucalyptus, black mangrove, and dryobalanops, and it has important implications:

- Maximized sunlight: By giving each other space, trees allow more sunlight to penetrate to the lower canopy and forest floor, benefiting saplings and understory plants.

- Reduced disease transfer: Avoiding physical contact limits the spread of leaf-borne pathogens and pests.

- Stability and resilience: Carefully spaced crowns reduce the risk of damage during storms by lessening how much wind force is transferred between trees.

Experiments using time-lapse photography have documented that as trees grow toward each other, their branches slow, change direction, or stop elongating upon sensing proximity. This reveals synchronous adaptation rather than random growth inhibition.

The Science of Tree Communication

Trees communicate using multiple strategies, forming rich networks both above and below ground. Understanding these communications reveals just how interconnected and social forests truly are.

Chemical Signals in the Air

When under attack by herbivores, certain tree species emit airborne chemicals that warn their neighbors of imminent danger. These signals can prompt neighboring trees to bolster their own chemical defenses—such as increasing bitter-tasting or toxic compounds within their leaves, making them less appetizing to insects or mammals.

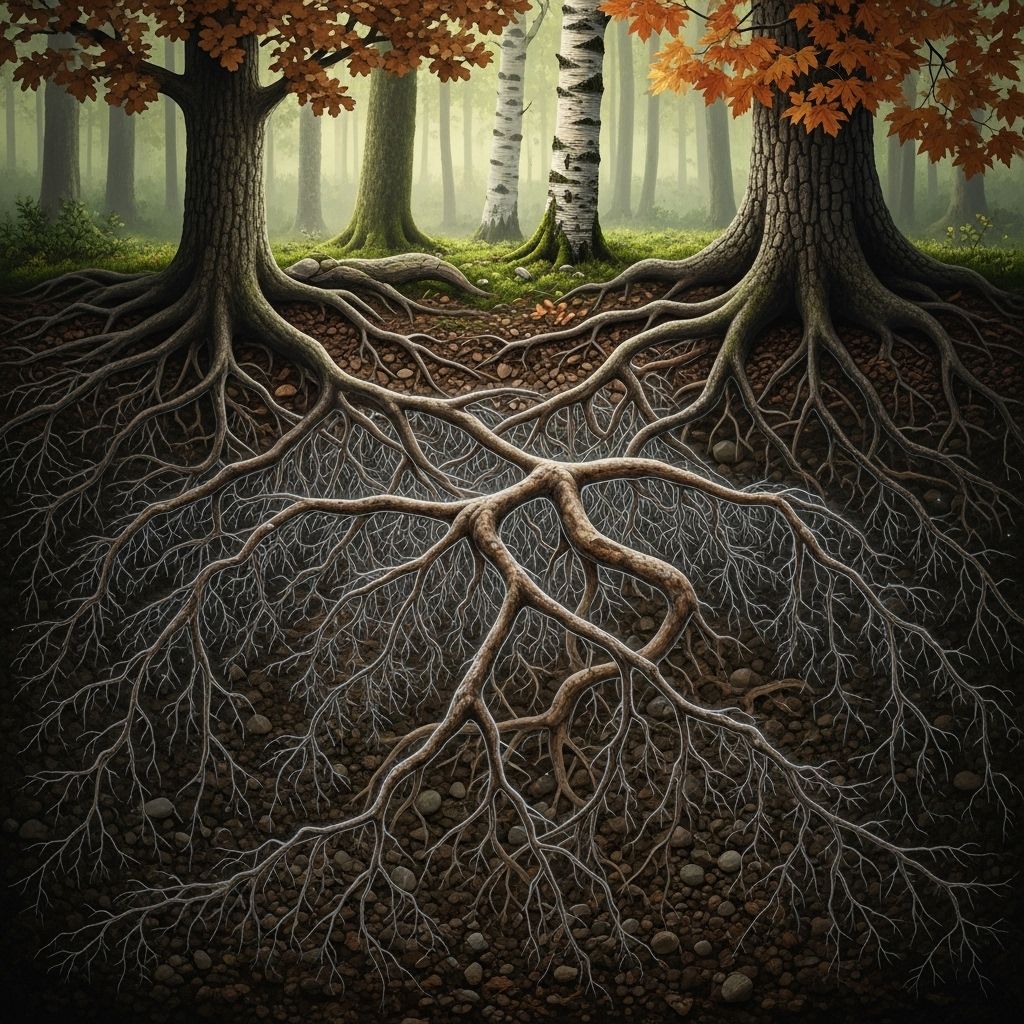

The Hidden Web: Mycorrhizal Networks

Below ground, a vast network of fungal filaments, called mycorrhizae, connects the roots of most trees in a forest. This network acts as both a communication channel and a resource-sharing system, so crucial it is sometimes nicknamed the “Wood Wide Web.”

- Signal relay: Through the fungal network, trees can transmit information about drought, disease, or even attacks from insects.

- Nutrient exchange: Older, larger trees often send excess sugars, water, and nutrients to saplings or distressed neighbors.

- Symbiotic fungi: Mycorrhizal fungi benefit by receiving sugars from tree roots in exchange for essential nutrients they extract from the soil.

Research has shown that mother trees—robust, mature specimens—often act as central hubs, nourishing younger trees, even those of different species, via these underground connections.

Mechanical Sensing and Response

Physical touch is another realm in which trees demonstrate awareness of their neighbors. Laboratory and field studies observe that when tree branches make contact, the rate of cell division and expansion in those areas can slow, halting further encroachment and reducing potential damage.

Trees as Cooperative Communities

This new perspective categorizes forests not simply as sites of ceaseless competition, but as cooperative communities in which individuals can nurture, warn, and defend one another. This shifts the popular narrative from “survival of the fittest” to a more nuanced “survival of the most cooperative.”

| Mode of Interaction | Examples in Trees | Ecological Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Above-ground signaling | Release of warning chemicals | Prepares neighbors for stress; builds collective defense |

| Crown shyness | Non-overlapping tree crowns | Maximizes light, reduces disease transfer |

| Mycorrhizal exchange | Sharing water, sugars, nutrients via fungal webs | Enhances resilience, supports young/sick trees |

| Mechanical sensing | Growth slows/stops upon touch | Prevents structural damage, balances space |

Case Study: Crown Shyness Across Species

Crown shyness has been most conspicuously documented in species like black mangrove (Avicennia germinans), dryobalanops (Dryobalanops aromatica), and even in some types of eucalyptus. Not every tree species demonstrates crown shyness, but where it occurs, its effects are dramatic—creating delicate lattices of light between canopies and enhancing overall forest health.

- Field studies in Southeast Asia and Australia have shown that young trees will modify growth patterns before branches touch, guided by both mechanical and light cues.

- In urban parks where human pruning replaces natural feedback, crown shyness can be less pronounced but still observable.

The existence of crown shyness raises tantalizing questions about the evolutionary advantages of cooperative, rather than merely competitive, plant behavior.

Implications for Forest Health and Management

A deeper understanding of how trees sense and respect their neighbors is changing forestry and conservation practices:

- Planting for diversity: Encouraging mixed-species stands that facilitate communication and support reduces disease risk and improves resilience to climate extremes.

- Selective thinning: Rather than clearcutting, thinning forests to natural-like densities preserves communal benefits.

- Respecting mother trees: Maintaining the largest, oldest trees ensures the persistence of network hubs that stabilize forests during environmental change.

- Supporting below-ground life: Avoiding fungicides and soil compaction helps mycorrhizal networks that trees depend on.

These approaches not only sustain the health of trees, but also nurture the wider ecosystem of animals, fungi, and other plants that forests support.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: How do trees actually sense their neighbors?

A: Trees detect neighbors by sensing changes in light quality, touching branches and leaves, and picking up chemical signals released by other trees. Underground, they can also sense chemicals produced by nearby roots and by interacting with mycorrhizal fungi.

Q: Is crown shyness found in all tree species?

A: No, crown shyness is most pronounced in certain tree species, such as black mangrove and eucalyptus. While common in some forests, the phenomenon is less apparent or absent in others depending on the biology of the trees involved.

Q: Why do trees share resources with one another?

A: Sharing resources, especially via mycorrhizal networks, increases the survival of young and stressed trees and enhances the stability and resilience of the entire forest community, benefitting all members over the long term.

Q: Can understanding tree cooperation influence urban forestry?

A: Absolutely. By designing urban spaces that allow for cooperative growth patterns and maintain fungal networks in the soil, city planners and arborists can cultivate trees that are healthier, longer-lived, and better integrated with local wildlife.

Q: What does this research say about plant intelligence?

A: While trees do not have brains, the ability to process complex information about their neighbors and modify behavior accordingly is a form of intelligence—and challenges outdated views of plants as passive or insentient organisms.

Why Trees Matter: Broader Ecological Lessons

Understanding how trees sense, communicate with, and support their neighbors reframes human relationships with forests. The old view of forests as arenas of unending struggle gives way to a richer picture of collaboration and mutual adaptation—a wisdom we can learn from as we face the challenges of environmental conservation.

- Healthy forests support biodiversity, moderate climate, resist pests naturally, and recover faster from disturbance.

- Trees that give each other space also promote light penetration, healthier undergrowth, and a balanced ecosystem for animals and insects.

- Recognizing the value of tree cooperation encourages the protection and thoughtful management of forests worldwide.

Conclusion: Trees as Neighbors, Not Just Individuals

Trees thrive not by ignoring their neighbors, but by paying close attention and adapting to them. Whether through crown shyness, chemical signaling, or shared fungal networks, trees create forests that are more than just a sum of their parts. In appreciating the intelligence and cooperation of trees, we take one step closer to fostering healthier, more resilient natural communities—and perhaps, more neighborly human societies as well.

References

- https://ecori.org/lincoln-treehugger-watches-in-despair-as-neighborhood-trees-fall-like-dominoes/

- https://www.greensourcetexas.org/articles/two-arlington-businesses-have-roots-owners-love-trees

- https://ibw21.org/commentary/reclaiming-tree-hugger/

- https://www.sustainablesanantonio.com/trees-are-aware-of-their-neighbors-and-give-them-room/

- https://humaneeducation.org/treehuggers-childrens-picture-books-honoring-trees/

- https://www.patagonia.com/stories/the-original-tree-huggers/story-71575.html

- https://trellis.net/article/evolution-tree-hugger/

Read full bio of Sneha Tete