How Mercury Gets Into Fish: Sources, Risks, and Safe Choices

Understanding how mercury enters aquatic ecosystems, impacts fish and humans, and how to make safer seafood choices.

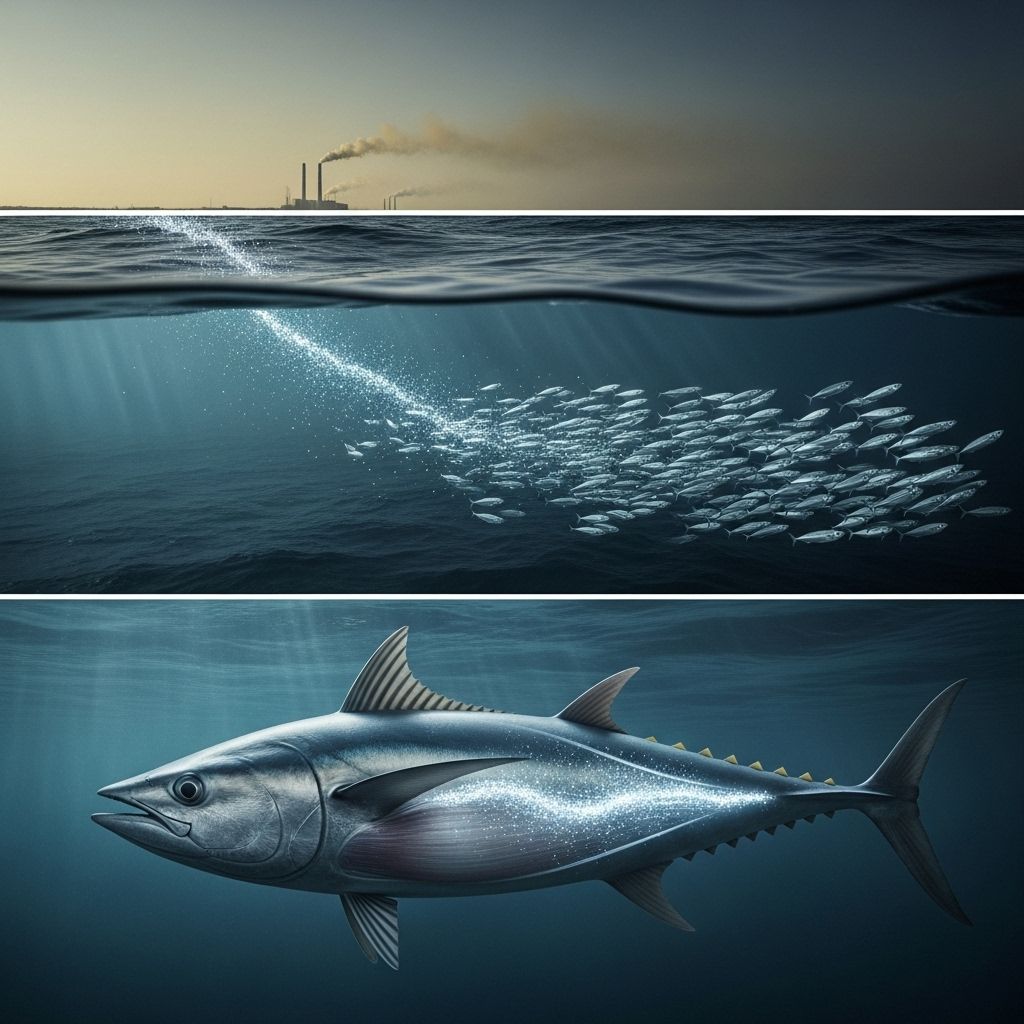

How Mercury Gets Into Fish

Mercury, a naturally occurring heavy metal, poses significant environmental and health risks as it accumulates in aquatic ecosystems. While some mercury originates from natural geological sources, human activities such as burning fossil fuels, incinerating waste, and certain industrial processes greatly amplify its presence. Once released, mercury circulates globally, entering water bodies either directly from air deposition or via contaminated runoff.

The Sources of Environmental Mercury

- Natural sources: Mercury is present at low levels in rocks, soils, and waters worldwide.

- Anthropogenic sources: The combustion of coal, oil, and natural gas; incineration of municipal and medical waste; and some manufacturing practices release significant amounts of mercury into the atmosphere.

- Runoff and leaching: Mercury from landfills, incinerators, wastewater treatment plants, and stormwater can leach into soils and waterways, further contributing to contamination.

Atmospheric Deposition and Aquatic Entry

Once released, mercury travels long distances in the atmosphere and eventually settles onto land and water surfaces through precipitation. From there, it can be washed into lakes, rivers, streams, and oceans.

Transformation of Mercury: From Elemental to Toxic

Mercury in its elemental and inorganic forms is less hazardous compared to its organic form. The most dangerous is methylmercury, created when microorganisms and bacteria in water convert inorganic mercury through a biochemical process called methylation.

Methylmercury Formation

- Bacteria in sediments and water transform mercury into methylmercury.

- This process is most active in warm, low-oxygen environments such as wetlands and the bottom sediments of lakes and rivers.

- Methylmercury is highly soluble and readily absorbed by living organisms.

Methylmercury in Aquatic Food Webs

Once formed, methylmercury is absorbed by floating microorganisms such as plankton. As plankton are eaten by small aquatic organisms, the mercury concentration increases at each stage of the food chain, a process known as bioaccumulation.

Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification: Mercury Moves Up the Food Chain

Methylmercury persists in the tissues of organisms, binding tightly to proteins in muscle (the meat of fish). Unlike some contaminants that remain mainly in the skin or fatty tissues, mercury cannot be removed through cleaning, cooking, or trimming the fish.

- Bioaccumulation: Mercury builds up inside organisms over time as they absorb more than they eliminate.

- Biomagnification: As small creatures are eaten by bigger fish, and those fish are consumed by even larger predators, mercury concentrations rise significantly at each level.

This pattern means predatory fish at the top of the food chain—often larger and older species—carry the greatest mercury burdens.

Which Fish Contain the Most Mercury?

Mercury content varies considerably by fish species, habitat, size, age, and diet.

| Fish Species | Mercury Level | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Tuna (particularly large species) | High | Predatory, large, long-lived marine fish |

| Shark, Ray, Swordfish, Orange Roughy | High | Top predators, accumulate mercury over years |

| Perch, Pike, Pikeperch (freshwater) | Moderate | Predatory, mid-level mercury burden |

| Salmon, Hake, Pollock, Trout | Low | Often smaller, shorter-lived fish |

| Shellfish (prawns, lobster, oysters) | Lowest | Non-predatory, short life cycle |

Factors increasing mercury levels in fish:

- Type of fish (predators vs. non-predators)

- Size and age (older, larger fish accumulate more mercury)

- Habitat and region (“hot spots” where local contamination is high)

- Diet (fish that eat other fish accumulate more mercury)

Mercury Hot Spots: Location Matters

Mercury concentration in fish varies not only by species but also by harvest location. “Hot spots”—areas with especially high mercury levels—can pose significant risk to fish consumers.

- Monitoring of mercury levels in different regions enables regulatory agencies to identify and manage risk areas.

- Research is ongoing in regions such as the Gulf of Mexico to develop predictive tools for identifying and preventing exposure from high-risk areas.

Human Exposure: Eating Fish Is the Main Pathway

Seafood is the primary source of mercury exposure for most humans. Consuming fish containing methylmercury allows the toxin to enter the body, where it can cross biological membranes and accumulate in tissues, especially the nervous system.

Health Risks of Mercury in Fish

- Neurological damage: Mercury primarily affects cells in the brain and spinal cord. Children, babies, and developing fetuses are especially vulnerable.

- Developmental issues: Prenatal exposure to mercury can impair cognitive development, motor skills, and sensory function in children.

- Other risks: High long-term exposure in adults can also impact the cardiovascular and immune systems.

The severity of health effects depends on the amount, duration, and timing of exposure, with risks greatest for unborn babies, infants, and young children.

Mercury Content in Fish: Research Findings

Scientific analysis reveals a wide range of mercury concentrations across fish species:

- Mercury levels in studied fish ranged from 0.004–0.827 mg/kg (arithmetic mean = 0.084 mg/kg).

- Mean content in marine fish: 0.100 mg/kg.

- Mean content in freshwater fish: 0.063 mg/kg.

- Tuna, especially large types, consistently showed the highest mercury levels; salmon, hake, and pollock had the lowest.

For most fish, measured mercury levels typically fall below regulatory safe limits, except for large predator species that may present risks if consumed frequently.

Tuna and Health Risk

Tuna, particularly yellowfin and large species, sometimes exceed recommended hazard quotients, making frequent consumption a concern—especially for vulnerable groups.

Safe Fish Choices: Minimizing Mercury Exposure

To reduce health risks, experts recommend choosing fish species known to be lower in mercury and managing the frequency and quantity of higher-risk species.

- Low-mercury fish: Shellfish (prawns, lobster, oysters), salmon (including canned), hake, pollock, trout, carp.

- High-mercury fish: Shark, swordfish, ray, orange roughy, large tuna.

Special precautions are advised for:

- Pregnant and lactating women

- Young children and infants

- Individuals with pre-existing neurological conditions

How to Reduce Your Exposure to Mercury from Fish

- Eat a variety of species to avoid concentrating exposure from any single high-mercury fish.

- Favor smaller, younger, non-predatory fish, which accumulate less mercury.

- Follow regional advisories and guidelines on safe seafood consumption.

- Stay informed about local “hot spots” or pollution advisories for recreational and commercial fishing areas.

Other Contaminants in Fish

Mercury is only one of several contaminants that may threaten fish and human health. Fish can also absorb substances such as PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), dioxins, and chlorinated pesticides from water, sediments, and food sources. Unlike mercury, many of these contaminants accumulate in fatty tissues and may be partially reduced by proper preparation, but they remain a concern in heavily polluted regions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Mercury in Fish

Q: Can mercury be removed by cooking or cleaning fish?

A: No. Mercury binds to muscle proteins and cannot be eliminated through cooking, cleaning, or filleting.

Q: Who is most at risk from mercury in fish?

A: Pregnant women, fetuses, infants, and young children are most vulnerable. It is important for these groups to limit their intake of high-mercury fish.

Q: Are farmed fish safer than wild-caught fish regarding mercury?

A: Farmed fish generally have lower mercury levels than wild predator fish, but risks vary by species and farming practices.

Q: Why do some regions or water bodies have higher mercury levels in fish?

A: Local environmental factors, industrial pollution, and atmospheric deposition can create “hot spots” where methylmercury levels are much higher.

Q: How often can I safely eat fish with moderate mercury levels?

A: Most health organizations recommend eating low-mercury fish several times a week, and limiting high-mercury species to occasional consumption, especially for sensitive groups.

Key Insights and Consumer Guidance

- Mercury pollution is an ongoing global challenge that affects aquatic ecosystems and human health.

- Understanding mercury sources, bioaccumulation patterns, and fish species differences enables informed seafood choices.

- Prioritizing low-mercury fish and monitoring regional advisories helps minimize health risks.

Further Resources

- Check local health advisories for fish consumption safety.

- Consult guides on mercury levels in fish to make informed decisions when purchasing or harvesting seafood.

- Stay updated on scientific research and regulatory changes affecting seafood safety.

References

- https://doh.wa.gov/community-and-environment/food/fish/contaminants-fish

- https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/mercury-in-fish

- https://coastalscience.noaa.gov/project/mercury-hot-spots-bioaccumulation-fish/

- https://epi.dph.ncdhhs.gov/oee/mercury/in_fish.html

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10457943/

- https://www.fda.gov/food/environmental-contaminants-food/mercury-levels-commercial-fish-and-shellfish-1990-2012

- https://health.ri.gov/mercury-poisoning/fish

- https://www.epa.gov/mercury/how-people-are-exposed-mercury

Read full bio of medha deb