Why ‘Ecosystem Services’ Is a Problematic, Limited Term

Examining why the concept of ecosystem services fails to capture nature’s intrinsic value and may hinder effective conservation.

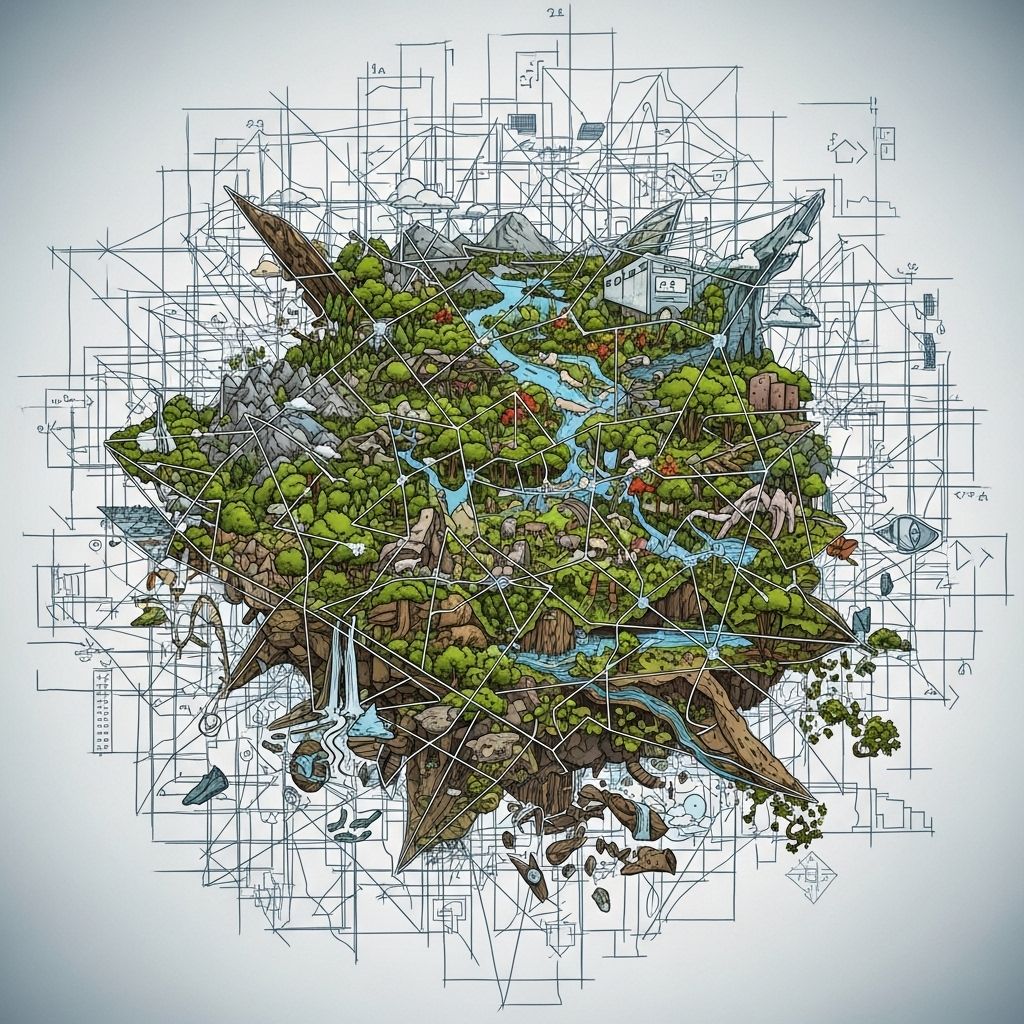

The concept of ecosystem services has gained prominence as a tool to convey the importance of nature by framing its value to humans in economic and utilitarian terms. While effective in drawing attention to conservation from policymakers and economists, many experts and ecologists argue that this framing is fundamentally limited and potentially harmful over the long term. It risks reducing nature’s vast complexity and beauty to a series of resources to be exploited and managed for human benefit alone.

Understanding the Concept of Ecosystem Services

The term ecosystem services refers to the benefits that humans derive from nature, including both tangible resources and intangible processes that sustain life on Earth. The United Nations Millennium Ecosystem Assessment categorizes these services into four main types:

- Provisioning Services: Material goods like food, water, timber, fibers, and genetic resources.

- Regulating Services: Benefits from ecosystem processes such as climate regulation, pollination, disease control, flood management, and water purification.

- Cultural Services: Non-material benefits including recreation, spiritual enrichment, educational opportunities, and aesthetic experiences.

- Supporting Services (or Habitat Services): Fundamental ecological functions like soil formation, nutrient cycling, and provision of habitats for species, which underpin the other services.

The concept was introduced to provide a common language for policymakers, businesses, and conservationists. By quantifying nature’s benefits, advocates hope it will make the case for preserving biodiversity and investing in nature more compelling to decision-makers who prioritize economic outcomes.

Where Did the Concept Come From?

Ecosystem services originated in the 1970s-1980s, but gained global attention following Robert Costanza’s influential 1997 study, which placed a dollar value on global ecosystem services ($33 trillion per year at the time). The United Nations Millennium Ecosystem Assessment further popularized the framework, providing a more standardized typology.

Since then, the term has become increasingly embedded in environmental policy, sustainable development, and conservation literature. It is commonly seen in international conventions, local land management decisions, governmental reports, and ecological research papers.

Key Arguments for the Limitations of ‘Ecosystem Services’

Despite its popularity, the term faces significant criticism. Critics assert that framing conservation in terms of ecosystem services is depressingly limited for several reasons:

- Reductionist Framing: It encourages viewing nature as a set of resources, valued only for their apparent utility. This risks ignoring the intrinsic value of ecosystems, species, and natural processes, which cannot be measured or monetized.

- Anthropocentric Perspective: The concept centers human needs and desires, sometimes at the expense of the wider web of life. Nature is treated as a commodity rather than a complex system with its own worth and rights.

- Potential for Perverse Outcomes: By focusing only on measurable services, the framework can sideline species, habitats, or ecological features deemed ‘less valuable’ because their benefits are intangible or unrecognized.

- Ignoring Long-Term and Systemic Values: Ecosystem services analysis often emphasizes short-term tangible benefits, undermining long-term resilience, adaptability, and dynamic ecological processes that support life on Earth.

- Economic Valuation Issues: Assigning monetary values to ecosystem services can lead to oversimplification, inaccuracy, and undervaluation—especially for non-market or poorly understood benefits like spiritual, cultural, or aesthetic values.

The Case of Bees and Pollination

To illustrate, consider the example of wild bees. Ecosystem services logic frames bees primarily as pollinators necessary for food production—a vital service, certainly. Yet this view ignores their evolutionary significance, unique biology, beauty, and the subtle ways they shape resilient ecosystems. When their ‘service’ no longer has market value (if, for example, we develop artificial pollination technologies), will society still value bees or permit their decline?

Intrinsic Value versus Instrumental Value

Intrinsic value is the value that nature holds in and of itself, independent of any benefit to humans. Many philosophers, ecologists, and indigenous cultures have long advocated for respecting nature’s right to exist, evolve, and flourish without reference to human utility.

By contrast, instrumental value—the basis of ecosystem services—is grounded in usefulness, and what nature ‘offers’ to us. Critics argue that when conservation rests solely on instrumental value, it becomes conditional and transactional. Ecosystems, species, and landscapes that fail to demonstrate direct benefits may receive little protection.

The Limits of Economic Value in Nature Conservation

Economic valuation is efficient for communicating with governments and companies, but fails to capture the full depth and complexity of relationships within ecosystems. Some problems with this approach include:

- Non-market Values: Many of nature’s benefits are not traded or measured in markets. Cultural, spiritual, psychological, and educational values are difficult to quantify.

- Dynamic Change: Ecosystems evolve, shift, and interact in unpredictable ways. Assigning static values risks missing hidden interactions, emergent properties, or essential adaptive cycles.

- Biodiversity Loss: Valuing only ‘profitable’ services can encourage loss or neglect of less immediately useful species and habitats, eroding the foundation of resilient, diverse ecosystems.

How the Term Can Backfire

Ironically, by insisting on proof of utility, the ecosystem services paradigm can reinforce destructive behaviors:

- Land managers may prioritize monoculture crops over true biodiversity, focusing on maximizing yield or carbon credits at the expense of complex habitats.

- Rare animals or plants without obvious ‘services’ may be overlooked or allowed to go extinct, as their survival does not ‘pay off’.

- Developers may extract short-term ecosystem value, ignoring long-term consequences and systemic degradation that are not factored into market values.

A Table: Comparing Values in Conservation

| Value Type | Definition | Examples | Risks if Ignored |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrumental/Ecosystem Services | Useful benefits to people | Water purification, timber, pollination | If service collapses, societal costs |

| Intrinsic Value | Worth beyond utility; existence and flourishing | All species, wilderness, aesthetic beauty | Loss of uniqueness, cultural impoverishment, reduced resilience |

| Systemic/Relational Value | Value through ecological relationships | Keystone species, nutrient cycling, food webs | Loss of interdependence, ecosystem collapse |

Alternative Approaches to Valuing Nature

Many conservationists advocate shifting away from a purely services-based framework. Alternative approaches include:

- Recognizing Intrinsic Value: Protect species, habitats, and ecological processes irrespective of their measurable benefits.

- Adopting Rights of Nature Laws: Legal frameworks that recognize ecosystems and species as subjects with rights to exist, regenerate, and thrive, not merely resources for exploitation.

- Holistic Conservation: Emphasizing ecological coherence, evolutionary processes, landscape connectivity, and culturally rooted stewardship.

- Biodiversity as a Foundation: Valuing genetic, species, and ecosystem diversity for its own sake, as the basis for resilience and adaptability.

The Role of Indigenous and Local Knowledge

Indigenous cultures and traditional societies often possess a view of nature rooted in respect, reciprocity, and stewardship. Their practices are frequently geared towards maintaining balance with the environment, honoring both practical benefits and spiritual or cultural connections to the land and its living beings.

Recognizing and integrating these perspectives is crucial for more equitable, lasting conservation, and may counter the narrowness of the ecosystem services paradigm.

Confronting the Challenges Ahead

The world faces escalating threats to ecosystems and biodiversity, including climate change, habitat destruction, pollution, and overexploitation. Lifelines such as fresh water, fertile soil, breathable air, and genetic diversity are at risk.

Decisions made today—about land use, stewardship, urban expansion, and agriculture—will shape the fate of countless species and the ability of natural systems to support humanity into the future. Conservation strategies must evolve beyond market-centered rationales to truly safeguard the planet’s rich tapestry of life.

What Can Be Done?

- Advocate for broader definitions of value: Support conservation policies that encompass intrinsic, relational, and systemic value—not just economic utility.

- Promote biodiversity and ecosystem integrity: Invest in protecting diverse habitats, rare species, and ecological processes that might not offer measurable ‘services’ but are vital for ecological health.

- Educate about nature’s complexity: Emphasize the interconnectedness of ecological processes, and the limitations of strictly utilitarian perspectives.

- Integrate traditional knowledge: Foster collaborations with indigenous peoples and local communities, incorporating diverse ways of relating to nature in conservation planning.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are ecosystem services?

A: Ecosystem services are the direct and indirect benefits people receive from natural ecosystems, such as clean air and water, climate regulation, food production, and recreational opportunities.

Q: Why is the concept of ecosystem services considered limited?

A: It is limited because it frames nature only in terms of its utility to humans, potentially ignoring intrinsic value, causing harm to species or habitats that lack clear ‘service’ value, and oversimplifying complex ecological relationships.

Q: Are there alternatives to the ecosystem services framework?

A: Yes. Alternatives include recognizing intrinsic value, adopting rights-based approaches for nature, integrating indigenous knowledge, and supporting conservation based on ecological integrity and biodiversity rather than utility alone.

Q: What happens if ecosystem services are lost?

A: The loss of ecosystem services—for example, pollination, water filtration, or climate regulation—can cause economic hardship, health crises, and environmental degradation, but focusing only on services may not be enough to prevent disasters caused by broader biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse.

Q: How can individuals help broaden the value framework for nature?

A: Individuals can support conservation efforts that value nature’s intrinsic worth, educate others about ecological complexity, advocate for inclusive policies, and learn from indigenous cultures about respectful stewardship of the natural world.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecosystem_service

- https://earth.org/what-are-ecosystem-services/

- https://www.nature.scot/scotlands-biodiversity/scottish-biodiversity-strategy/ecosystem-approach/ecosystem-services-natures-benefits

- https://www.green.earth/blog/10-vital-ecosystem-services-sustaining-life-on-earth

- https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Understanding-Conservation/Ecosystem-Services

- https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecosystem-services-research

- https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/120-a152

- https://unece.org/ecosystem-services-0

Read full bio of medha deb