Bill McKibben and the Art of Slow Travel: Rethinking How We Move

Exploring Bill McKibben’s deep case for slow travel and its pivotal role in cultivating climate consciousness, community, and meaningful connection.

Bill McKibben and the Art of Slow Travel: A Journey of Meaning, Place, and Climate

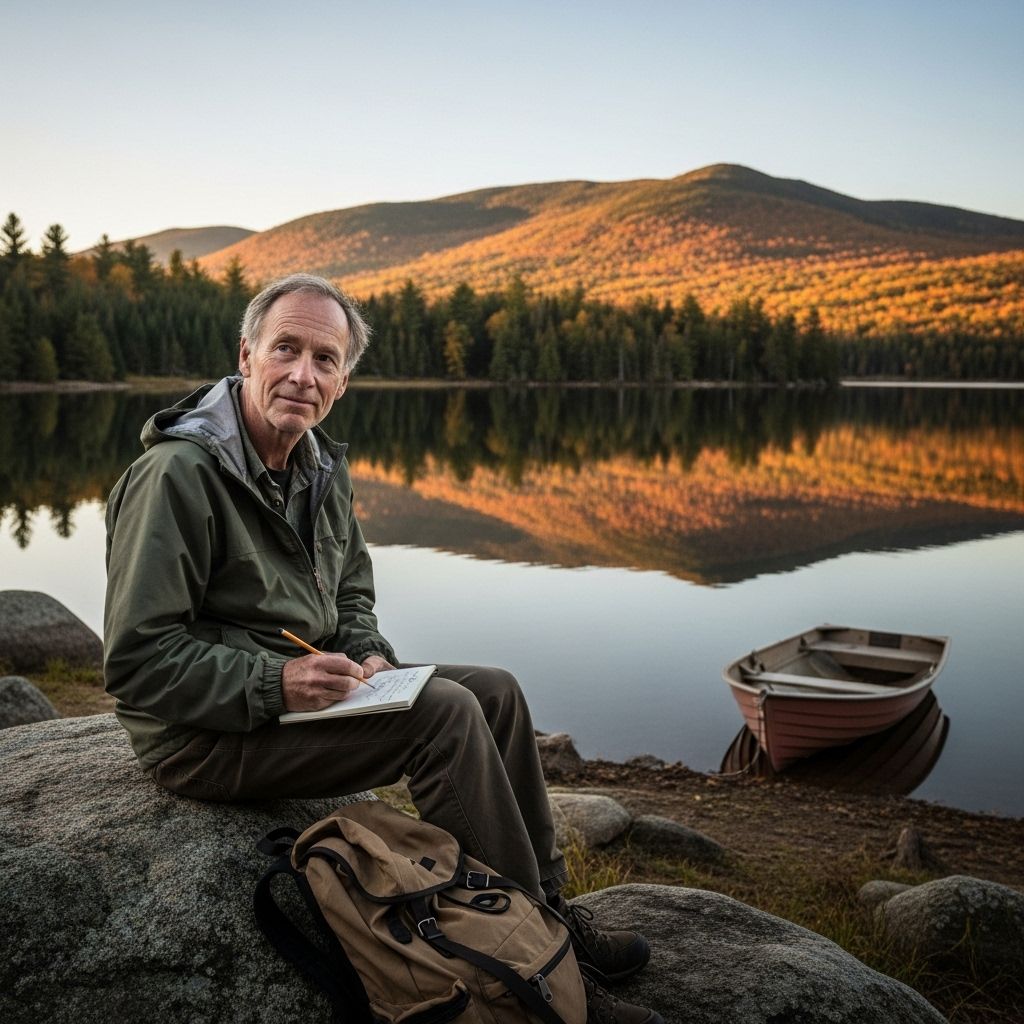

In a world obsessed with speed, connectivity, and convenience, Bill McKibben—renowned environmental author and climate activist—argues that slow travel is more than a luxury: it’s a vital tool in reawakening our sense of place, rebuilding community, and honestly confronting the global climate emergency. Through his life, work, and advocacy, McKibben paints a compelling portrait of how deliberate, mindful travel can reshape not just individual lives but the future of the planet itself.

Understanding Slow Travel

Slow travel is a philosophy that celebrates deliberate journeys over rushed arrivals, local exploration instead of far-flung conquests, and meaningful connection in place of the fleeting novelty of destination-focused tourism. Rather than seeking to see more, faster, slow travelers seek to understand more, deeper—privileging the journey, the landscapes, and the communities along the way.

- Local immersion: Experiencing a destination by engaging with its people, culture, and environment rather than skimming highlights.

- Time-rich, carbon-light journeys: Choosing trains over planes, boots over wheels, and patience over haste to reduce one’s environmental footprint.

- Mindful movement: Using travel to build presence and awareness, fostering respect for both nature and culture.

For McKibben, the principle of slow travel is rooted in both ecological ethics and the deep fulfillment that comes from genuine engagement with the world around us.

The Birth of a Slow Travel Advocate

Bill McKibben grew up in an era when mobility and speed were lauded as measures of progress. Yet, his formative experiences—especially the long, contemplative journeys across the wilds of Vermont and the Adirondacks chronicled in his book Wandering Home—offered a different vision. Through these walks, he discovered that “the dominant emotion in The End of Nature is less fear than it is sadness and grief,” reflecting on the loss of wildness, community, and winter itself due to climate change.

His slow travels led him to vital insights:

- Contact with place matters. Experiencing the natural world at a human pace creates a bond that is hard to ignore, and even harder to destroy.

- Community thrives on interdependence. Slowing down makes us reliant on, and connected to, others—a crucial antidote to alienation.

- Climate awareness is personal. Living amidst the rhythms of the land, one cannot help but feel the impact of a warming globe—an awareness that is abstracted away when traveling in bubbles of speed and comfort.

The Problem with Speed

Fast travel—dominated by air travel and highways—has become emblematic of the modern age, but McKibben identifies several core problems with our addiction to speed:

- Environmental Impact: Rapid movement across great distances, especially by plane, is carbon-intensive and exacerbates climate change.

- Disconnection from Place: Speed strips away the incremental, rich experiences of people and landscapes between origin and destination.

- Cultural Erosion: Mass tourism homogenizes destinations and erodes the unique character of local communities.

McKibben’s writing and activism frequently highlight the disconnect that comes from living and traveling too quickly. A world experienced at 30,000 feet becomes a blur—unable to impart the lessons or wonders that come from walking, cycling, or slowly traversing its contours.

Climate Change: The Urgency of Rethinking Travel

Having dedicated much of his life to warning about and fighting climate change, McKibben situates slow travel as a crucial, tactical response to the crisis. According to him, “at our latitude, winter is on average about two to three weeks shorter now than it was in 1970,” a statistic that brings the abstract concept of climate change into stark, personal focus.

He identifies three major imperatives:

- Reducing personal carbon emissions: Prioritizing trains, buses, bicycles, and feet over planes and cars.

- Influencing systemic change: Advocating for improved public transportation and low-carbon infrastructure.

- Reviving localism: Choosing destinations—whether for pleasure, work, or necessity—that require less movement and reward deeper connection.

McKibben emphasizes that the shift to slower travel is not just about individual virtue, but about encouraging larger shifts: “All that’s necessary is contact with… The story of what happened to American agriculture is probably the single most important news story of the last century. We went from 50 percent of the population living on farms to less than 1 percent. There are far more prisoners in the U.S. than there are farmers.”

Reviving Community and Place

One of the most poignant themes in McKibben’s thinking is the role of travel in rebuilding fractured communities. In Wandering Home, he describes visiting farm families, vintners, and foresters, noting that “community is as endangered by surplus as it is by deficit.” Real estate booms in rural areas may bring money, but “when there’s too much money floating around, it enables people to have no need of each other.”

- Mutual reliance: In places where people slow down, they need to help and be helped.

- Endangered intimacy: The influx of wealth and vacationers from cities reshapes rural regions, pricing out long-term residents and weakening social bonds.

- Slow travel as solution: By fostering deliberate encounters and exchanges, slower forms of movement help rebuild necessary ties of trust and cooperation.

Case Studies from McKibben’s Life and Work

Through decades of advocacy, writing, and personal experience, McKibben offers instructive examples of how slow travel creates insight and catalyzes change:

- The Long Walks: From Vermont to the Adirondacks, McKibben’s journeys are rich with encounters—not just with nature, but with craftspeople, activists, and fellow travelers.

- Local Agriculture: Meeting farmers and vintners intimately connected to land and climate underscores the fragility and resilience of local food systems.

- Renewable Energy Battles: Navigating community debates over wind turbines and solar installations demonstrates how place-based perspectives can recalibrate environmental values and priorities.

By experiencing his region on foot, bicycle, and train, McKibben not only reduces his impact but learns firsthand about the intricacies of local economies, natural habitats, and small-town character.

Practical Tips for Embracing Slow Travel

- Start local: Explore neighborhoods and towns by foot, bike, or public transit before venturing further afield.

- Prioritize proximity: Choose destinations that can be reached easily and enjoyably without flying.

- Savor the journey: Seek out routes—be they walking trails, rail lines, or waterways—that reveal the nuances of a landscape.

- Engage with community: Support local businesses, participate in regional festivals, and seek conversations with residents.

- Reflect as you go: Keep a travel journal, sketchbook, or camera to record deeper observations beyond Instagram snapshots.

Slow Travel and the Future: Building Resilience

As global crises—from climate change to pandemics—interrupt the expectation of frictionless movement, slow travel emerges as a model of resilience. McKibben envisions a world where communities not only survive but thrive by investing in local infrastructure, supporting homegrown food and culture, and embracing the limitations imposed by honest environmental reckoning.

- Decentralization: Slow travel inspires us to redistribute our time and resources more equitably, reducing stress on overloaded hotspots and supporting overlooked regions.

- Stewardship: Frequenting fewer places for longer periods fosters a sense of responsibility and care for those environments.

- Creativity: Constrained by slower modes and routes, travelers become more inventive in their explorations, often discovering hidden or forgotten treasures.

Slow Travel vs. Fast Travel: Head-to-Head Comparison

| Aspect | Slow Travel | Fast Travel |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Emissions | Low (train, bus, foot, bike) | High (air, car, cruise ship) |

| Connection to Place | Deep and immersive | Superficial, destination-focused |

| Impact on Community | Supports local businesses, builds ties | Often bypasses or overwhelms locals |

| Pace of Experience | Deliberate, time-rich | Rushed, schedule-driven |

The Emotional and Spiritual Rewards

For McKibben, slow travel is not only a strategy for sustainability—it’s a source of joy and meaning. He writes with “less fear than sadness and grief” about climate loss, but his hope emerges in the small, tangible pleasures that slow travel makes possible: a conversation with an old farmer, the quiet hush of new-fallen snow, or the satisfaction of contributing to a community meal.

By foregrounding these rewards, McKibben invites us to see slow travel as a gift—an antidote to hypermodern anxieties and a path to greater presence, gratitude, and belonging.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What exactly is ‘slow travel’ according to Bill McKibben?

A: Slow travel is traveling deliberately and mindfully, favoring trains, walking, and regional journeys over flights and rapid tourism. It emphasizes environmental responsibility, deep engagement with place, and connecting to local communities.

Q: How does slow travel help combat climate change?

A: By reducing the need for high-carbon, long-distance modes of travel, slow travel directly cuts emissions. It also fosters climate awareness and strengthens the case for local sustainability and community action.

Q: Isn’t slow travel less convenient?

A: While slow travel can be less immediately convenient, it offers compensating rewards: richer experiences, stronger local economies, better mental health, and a smaller ecological footprint.

Q: Can everyone practice slow travel?

A: Slow travel can take many forms and does not always require extensive leisure time or resources. It can mean rediscovering your city, region, or country, and even small changes—like swapping a car ride for a bike trip—can make a difference.

Conclusion: The Road Ahead

Bill McKibben’s vision of slow travel is not about nostalgia or sacrifice. It’s a call to reinvent our relationship with movement, place, and each other. He urges us to resist the temptations of speed and abundance, and to instead cultivate connections—both human and ecological—that can withstand the stresses of a changing world. In doing so, slow travel becomes not just an act of personal fulfillment, but a cornerstone of climate justice, resilience, and renewed belonging.

References

- https://www.thesunmagazine.org/articles/22788-dream-a-little-dream

- https://newrepublic.com/article/199748/bill-mckibben-far-too-sunny-outlook-solar-power

- https://mothere.substack.com/p/the-voices-of-earth-week

- https://www.adirondackexplorer.org/environment/clean-energy/where-does-the-climate-movement-go-from-here-an-interview-with-bill-mckibben/

- https://coveringclimatenow.org/from-us-story/honoring-bill-mckibben-for-a-lifetime-of-ground-breaking-climate-journalism/

Read full bio of medha deb